After limping along most of the year, the films of 2005 ended with a rare body of work fierce in moral and even spiritual inspection.

For a long time in 2005, movie studios and theater owners were fearing the worst box office year ever. By early fall, studio heads were confessing that there was something, well, defective with their product, or at least with the timing of the product being put out there. Audiences simply seemed less credulous than usual, less susceptible to swallowing the typical Hollywood happy ending. Maybe it was the sober realities of a war that would not go away, or middle-class frustration with health care, or an economic non-boom, the toll of aging parents, renegade kids–whatever, audiences did not seem pabulum-susceptible.

The biggest flick of the summer seemed to fit the mood. In the less than happy Star Wars: Episode III–The Revenge of the Sith, George Lucas completed the moral transformation of young Anakin Skywalker into the forbidding darkness called Darth Vader, redeemed though Vader will be (connoisseurs of the series will remember) at the very end of The Return of the Jedi (1983). And surely the biggest disappointment of the movie year was cheery Opie (Ron Howard) doing Cinderella Man, starring real-life brawler Russell Crowe as fabled fighter James J. Braddock and Renee Zellweger in the plucky-wife role once played by Sally Field. The public wouldn’t have it–not this time, at least. Ron Howard’s flick went flat like a fighter caught with a first-round sucker punch. Its attempted resurrection in DVD release didn’t go so well either.

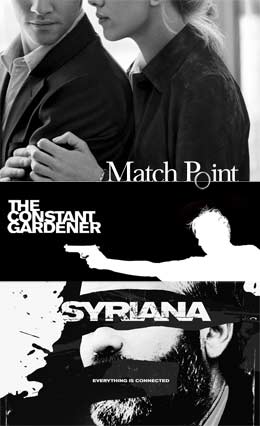

Then, the end of the year brought a remarkable turn in film-viewing fortunes. Studios always release their best at year’s end to make a strong impression on the short memories of Academy Awards voters, but 2005 produced something special. One after another, in too short a time, appeared a whole spate of wonderful films, many stylistically fresh and forceful, and all dipped in utter moral seriousness. It has in fact been a long, long time since filmdom turned out a body of such fierce moral and even spiritual inspection.

The series began with the film adaptation of John Le Carr?’s The Constant Gardener. Le Carr? is the British novelist of espionage and skullduggery in general. Many of his best-selling novels have ended up on the big screen, the very best being the 1970s BBC version of his Smiley novels, starring Alec Guinness. The Constant Gardener tells the story of corruption on the part of global pharmaceutical firms set in an impoverished and AIDSstricken Kenya. Director Fernando Meirelles (City of God, 2002) gives the film a searing over-ripeness as if the whole place is in rot, as hell itself might be.  The visual texture accentuates both the situation’s extremity of suffering and depth of moral distortion. The big drug companies have been using Africa to dump or test dubious product on the unsuspecting masses while their public face looks humane and generous. Ralph Fiennes plays Justin Quayle, a diffi- dent mid-level British diplomat, whose radical young wife goes missing during her back-country snooping of disease trajectories. The usually timorous Quayle– his hobby is tending plants–sets about finding the truth of what proves to be murder, and of exactly who did it for what reasons. The superb acting by Fiennes and Rachel Weisz (winner of Golden Globe for Best Supporting Actress) makes the implausible relationship between the quiet Quayle and the feisty Tessa both real and fetching. Not at all the usual who-done-it (Le Carr?’s novels never are), the film strips down his sprawling, even Byzantine plot but keeps its devastating moral impact. Le Carr?’s vision has not gotten cheerier over the years, and the film stays true to his somber appraisal of the desperate pass at which Western rectitude has arrived. With the Soviets gone as a moral competitor on the world stage, the operative but unspoken mandate seems to be plain old plunder with only the most casual nod toward any kind of altruistic cover for corporate greed.

The visual texture accentuates both the situation’s extremity of suffering and depth of moral distortion. The big drug companies have been using Africa to dump or test dubious product on the unsuspecting masses while their public face looks humane and generous. Ralph Fiennes plays Justin Quayle, a diffi- dent mid-level British diplomat, whose radical young wife goes missing during her back-country snooping of disease trajectories. The usually timorous Quayle– his hobby is tending plants–sets about finding the truth of what proves to be murder, and of exactly who did it for what reasons. The superb acting by Fiennes and Rachel Weisz (winner of Golden Globe for Best Supporting Actress) makes the implausible relationship between the quiet Quayle and the feisty Tessa both real and fetching. Not at all the usual who-done-it (Le Carr?’s novels never are), the film strips down his sprawling, even Byzantine plot but keeps its devastating moral impact. Le Carr?’s vision has not gotten cheerier over the years, and the film stays true to his somber appraisal of the desperate pass at which Western rectitude has arrived. With the Soviets gone as a moral competitor on the world stage, the operative but unspoken mandate seems to be plain old plunder with only the most casual nod toward any kind of altruistic cover for corporate greed.

Very much in the same mold is Syriana, a complex take on corporate and government collusion at manipulating global oil supplies to escalate prices. What saves this film from soppy liberal paranoia is some measure of plausibility and the spare efficiency of its storytelling in both narrative and acting. It presents no blackhatted villains, for everybody dwells in the mire of moral ambiguity and complicity. That’s true of the aging CIA agent-assassin (George Clooney), whom the agency deigns to leave out in the cold, as it is of the na?ve American macroeconomist (Matt Damon), who dares to advise oil potentates. And these are the good guys, relatively speaking. The skein of horror leads to displaced Arab oil workers who prove susceptible to the blandishments of radicals who want to blow the West straight to hell–a fate that, according to Syriana, it might well deserve.

Writer-director Stephen Gaghan, writer of Traffic (2000), a similarly grim overview of the illegal drug trade, displays his subject’s pervasive greed and corruption with stunning geographical agility, shifting locales from shiny boardrooms to desert expanses whose stark emptiness mirrors the hopelessness of its angry nomads. In countless ways, the movie tells us, the least accurate measure of the cost of oil is dollars and cents. As for the politics of justice, well, the perpetuation of Middle-Eastern instability and terror prospers dealers of all sorts. In the life-imitates-art category, as I write this, on January 30, ExxonMobil posted the largest annual profit ever by any American company. “By some measures,” The New York Timesgoes on to say, “Exxon became richer than some of world’s largest oil-producing nations”–Indonesia, for instance, the world’s fourth most populous country with 242 million people but whose GDP of $245 billion lagged pitifully behind ExxonMobil’s 2005 revenue of $371 billion.

With Good Night, and Good Luck we get closer to verifiable history, but still stay in a land fraught with shadows, where virtue is used as a cloak for chicanery. Specifically, we watch the response of CBS news pioneer Edward R. Murrow to the hostilities of notorious red-baiting Wisconsin Senator Joseph McCarthy. David Strathairn is a wonder as Murrow, doing his subject as a humorless, and fearless, straight-shooter who, the filmmakers relish pointing out, envisioned a high role for television news. Co-written and directed by actor George Clooney and effectively shot in ’50s-era black-and-white, the film is compact and direct. Perhaps to a fault. While we learn a few things about the lives of his associates, the answer to what makes Murrow himself tick remains obscure at best. The origins and writhings of his moral fire seem as remote as Olympus, which is where the filmmakers think he belongs. If the film has a shortcoming, it is that we have little sense of what else there is to the man besides pure conscience.

On the other hand, in Capote, which may be the year’s best film, viewers learn rather more than they would like about the main character, the late Truman Capote, celebrated novelist, glitterati bon vivant, and, in his last years, a pathetic sort of media spectacle.

|

If the film has a shortcoming, it’s that we have little sense of what else there is to the man besides pure conscience. |

The film fixes on the young Capote, wonderfully played by the marvelously talented Phillip Seymour Hoffman, winner this year of the Golden Globe for best actor. At the film’s beginning he proposes to New Yorker editor William Shawn (Bob Balaban) that he write an essay on the reaction of a small town in Kansas to the slaying of the four members of a rural farm family. With him to Kansas goes his childhood friend and research assistant, Harper Lee (Catherine Keener), the film’s moral compass, who will soon achieve her own notable success with To Kill a Mockingbird (1960). In efficient and telling manner the film details the shift in Capote’s focus from the town to, once they are apprehended, the killers: two drifters named Richard Hickock (Mark Pellegrino) and Perry Smith (Clifton Collins Jr.). Capote’s fascination with Smith, a talented and thoughtful man and the one who did the killings, quickly evolves into a much-anticipated book, In Cold Blood, which deploys a new art form in itself, the “non-fiction novel.” (This was the opposite, perhaps, of James Frey’s recent Oprah-ized and now scandal-ridden “fictional memoir,” A Million Little Pieces. Apparently, then as now, our culture worries about how best to tell the truth.)Truth-telling becomes Capote’s central moral problem as he spins deceptions of multiple kinds to get Perry Smith, who has come to regard Capote as a trusted friend, to spill the beans on which of the two did the actual shootings–and also to die in a timely fashion so Capote can publish his book.

|

Capote haunts the viewer with incessant questions about the omnivorous self manifested in a thousand beguiling small compromises. |

Suffice it to say, Capote increasingly finds himself in a profound moral bind wherein he must choose one route or another. The cost for his wrong choices, the film suggests, not only incapacitates Capote’s talent ever after, but blights his soul and, subsequently, his personal and public lives. Etched like a woodcut in a stark cinematography, Capote haunts the viewer with its incessant questions about the omnivorous self manifested in a thousand beguiling small compromises, whether these be in behalf of “art,” fame, politics, or God.That choosing the self over compassion, the summation of the other virtues, ends in hell, at least of a personal if not the traditional religious sort, seems also to be the judgment of Woody Allen in his dead-serious new film, Matchpoint. It is a tale of polite and handsome ex-tennis pro, Chris Wilton (Jonathan Rhys Meyers), who segues from instructor at a posh London tennis club to marriage into a very prosperous London family. Hard work and especially luck, as Allen continually emphasizes, pay off for Wilton. Born poor and Irish, he clawed his way into professional tennis, and after his retirement, low-keyed charm and good looks have done the rest: with the sweet, fancy wife come a two-story, glass-fronted apartment on the Thames and lavish living on the fast-track in one of daddy’s companies. Wilton does seem a decentenough fellow–sincere, sensitive, wellmeaning, opera-loving, and duly grateful for his good fortune. The only rub, so to speak, is Nola Rice (Scarlett Johansson), his future brother-in-law’s ex-fianc?e, a fabulously sexy American expat and wanna-be actress. This young woman the smooth, self-contained Chris cannot resist, and for no very good reason he imperils all his family favor for, well, “love or lust,” as he himself questions at one point. Once again, brains and taste do not in Allen’s world deter one from stupidity, cowardice, and meanness.

The film is superbly told, and Allen’s run-up to its crisis imparts ample dread. Wilton has all the choice in the world and seemingly more than enough good sense, but he heedlessly charges ahead in rank self-indulgence and then, when things sour, desperation. Throughout, Allen replays central questions from his greatest film, Crimes and Misdemeanors (1989), wherein well-heeled and cultured ophthalmologist Judah Rosenthal (Martin Landau) murders his bothersome mistress (Anjelica Huston), only to fall into paralyzing guilt that eventually, much to his surprise, disappears. Off he goes scot-free, morally and legally, back into his privileged life, happier than ever. If Crimes pushes hard–and it does–for the notion of a random, amoral universe, Matchpoint offers sterner stuff, suggesting that while chance or luck account for good or bad fortune, living with the consequences, bad or good, is quite another matter. The world may indeed be mute on why the rain falls on the just or why the wicked prosper, but how one behaves within that apparent caprice, whether it be Darwinian or divine, determines the measure of one’s ease within existence itself.

Chance looms large as well in director Ang Lee’s much-heralded tale of two young cowboys who summer sheep on the high ranges of Brokeback Mountain in Wyoming. Alone out there far from everyone else, they find themselves, much to their surprise, in a passionate sexual relationship.

|

Brokeback Mountain limns due reverence for the fathomless and forever-unrecoverable tenderness of genuine love. |

Afterwards, though amply closeted back in their small towns (the story begins in the 1960s), their intermittent times together become to a large extent the “be all” of their lives. From the start, Jack Twist (Jake Gyllenhaal) seems more accepting of the strange taboo he finds himself in, but Ennis Del Mar (Heath Ledger) chafes and thrashes, at once angry, yearning, and inarticulate, always uncertain of the rightness of their bond. The two men go, not very successfully, their separate ways to marriage and fatherhood, but over the decades of their straight lives, nothing rivals their regular fishing trips together at the lake on Brokeback. And on the frustration goes till the bond ceases (no telling endings here).Hardscrabble lives wear the two down, emotionally as much as physically. Lee pits their long, anguished relationship against, on the one hand, the indifferent majesty of the mountains and, on the other, the loathing of their times and especially of their constricted locales. What resounds throughout Brokeback Mountain is the wrenching poignancy of a bond thwarted in just about every way by the world in which it transpires. The term social tragedy seems grossly inadequate to conjure up the pathos of the conclusion, for what emerges, even in the bewildered Ennis, is due reverence for the fathomless and forever-unrecoverable tenderness of genuine love. This is a film magnificent in its spectacular setting and photography, to be sure, but its majesty shines clearer still in the exquisite care with which story-writer Annie Proulx, screenwriter Larry McMurtry, and director Lee limn the complex exactions of heart and land in mediating the soul’s thirst for completion.

These films–and they are by no means the only “best” of the year–supply bracing gifts, as good art should, to tax the brain but also to break the heart and flay the soul. The films speak for themselves in spelling out life’s toll in blood and tears–in what people do to themselves and each other for the damnedest of reasons. They are not, for sure, a cheery bunch of movies, but the cinematic story-telling again and again is just gorgeous, finding the means to do justice to the tales told. And as tragic as these many stories seem, their tone is not so much rage as lament, the keening of humankind’s lostness in its long exile from the place that the Shaker hymn calls “the land just right…the valley of love and delight.”