Sarina Gruver Moore is guest-blogging for the summer, when she most longs for home in the Pacific Northwest. She teaches in the English department at Calvin College.

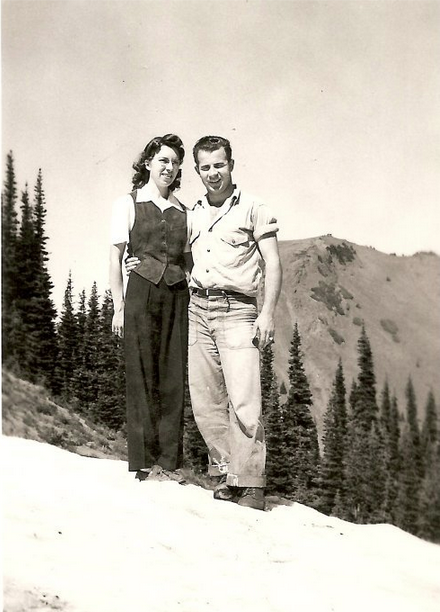

In the summer of 1941, my maternal grandparents were meeting and falling in love and living their young lives at full tilt, spinning along with the rest of the world toward war.

By April of 1942, Jasper had entered the service and Margaret was finishing her nurses’ training, both of them ready to do their duty. So in mid-June, when Jasper was told that he’d be given a long weekend over the Fourth of July, they decided to marry.

There are only a handful of wedding photos that I know of, but from the photos and family stories*, it’s clear that they effortlessly achieved the kind of simple, elegant wedding the rest of us can only pin in our dreams. All military personnel had to wear their uniforms for their entire length of service, so there wasn’t an option of a suit or a tuxedo for the groom. The bride sewed her own elegant, blue suit and paired it with white gloves, a white blouse, and a saucer hat. The wedding was at the First Baptist Church in Shelton, Washington. A lady at the church made the wedding cake, Pastor Bovee officiated, and the wedding attendants (one each) were chosen according to who could come given the gas rationing. The flowers were blue delphiniums, white gladiolas, and red carnations that the bride arranged herself. Their honeymoon was traveling to Seattle to be ready for Jasper to go back to work on July 5th at the Coast Guard office in the old Federal Building. In a time of serious housing shortages, they were grateful for the tiny apartment they found, and Margaret began her professional life as a nurse.

Soon, though, Jasper was sent to San Francisco for more training. Margaret followed behind and found work at a new hospital. Then Jasper was sent by troop train to Seneca, Illinois, where the new Landing Ship, Tank (LST) carriers were being built (his was number 202 out of 1050 ships). With his fellow Coast Guardsmen, Jasper sailed the new ship down the Mississippi to New Orleans—more training, more supplies, more waiting. Margaret took a long cross-country bus ride to New Orleans to join him.

In April of 1943, one year after he enlisted, Jasper sailed with the crew of LST 202 from New Orleans, through the Panama Canal, to San Diego. They loaded up jeeps, tanks, and troops and headed for the South Pacific. Cape Gloucester, Finschaven, Saidor, Aitape, Hollandia, Wadke, Biak, Numfoor, and the Admiralty Islands—eleven assaults in eighteen months. During battles, Jasper manned a ship gun. During landing assaults, he came in on the second or third wave of landings. Off-loading tanks, supplies, and men while the tide was out, they’d scramble to load up junked equipment, the wounded, prisoners, and to bury the US dead and get back off the beach before low tide. Sniper shots were thrown in just for good measure. My grandmother, now back in their hometown of Port Angeles, worked at the local hospital and wrote him letters with a fountain pen I later inherited.

After the war, my grandfather joined the local police force and my grandmother left nursing to raise their children—six, eventually. They planted a huge garden, hunted and hiked the Pacific Northwest, smoked their own fish, canned and jammed and preserved food. They served their church faithfully for decades—one of my earliest memories of my grandfather is watching him count the change at their kitchen table from that week’s offering, every penny meticulously accounted for. My grandmother sewed everyone’s clothes and washed everything with one of those hand-cranked “washing machines” (scare quotes meaningful here). My mother remembers going down into the basement on a Saturday evening and seeing 21 tiny, handmade dresses lined up, each ruffle carefully ironed: one week’s worth of dresses for each of the three girls. My grandmother also grew beautiful roses. When I was ten years old, I mentioned that “Pink Peace” was my favorite (it still is). After that, every time I visited or came home from college in the summer, up until my last visit when she was 90 years old, she would send me home with the most beautiful of the Pink Peace blooms—the cut stems carefully wrapped in wet paper towels and aluminum foil.

Their one luxury was a cabin my grandfather built in the early 1950s on a deep, glacial lake. The cabin had an outhouse and no running water. But it did have a dock and a fireplace, and just about every Fourth of July while I was growing up some of the many cousins and aunts and uncles would meet there to spend the day plunging into the cold, cold water, splutter-gasping for air, laughing at the shock. Someone would build a fire. Someone else would unpack a Jello cake (red, white, and blue, obviously). Near twilight, someone would encourage my grandfather—who had a voice like Johnny Cash—to yodel.

As people of their generation did, they knew both life at war and life at peace, and they taught me by their example to be grateful for an ordinary life—beautiful in its everydayness. They were strong and good and humble people who conquered mountains–both literal and metaphorical.

So this weekend, I’m packing up my family and we’re headed North, toward old-growth forests and deep, glacial lakes and camp fires and Jello cakes. It’s as close as I can get to my grandparents.

Happy Fourth of July.

*My thanks to my mother, who is an excellent historian and genealogist and from whom I learned all the details of my grandfather’s war service.