I wasn’t born and reared here. My home–I’m not sure how anyone finally defines that word–is really the western shore of Lake Michigan, where sunrise is almost always worth catching, but sunsets are, well, meh. When, initially, I lived out here on the emerald edge of the Great Plains, my most immediate adjustment was to realize that there was an east. Where I was reared, the big lake was all there was to “east.” (See that M on Lake Michigan? Go west to the shore. That’s where I grew up.)

It’s not difficult to simply look over or past the neighborhood where you live, to be taken in and to love particulars, its cities or towns. Out here, even counties are quite colorfully distinguishable–“Sioux County” isn’t “Lyon County,” as citizens of each are likely to say, rolling their eyes. Neighbors we are, but the labels mean more than simple geography, things we learn to love and hate, things that can consume us.

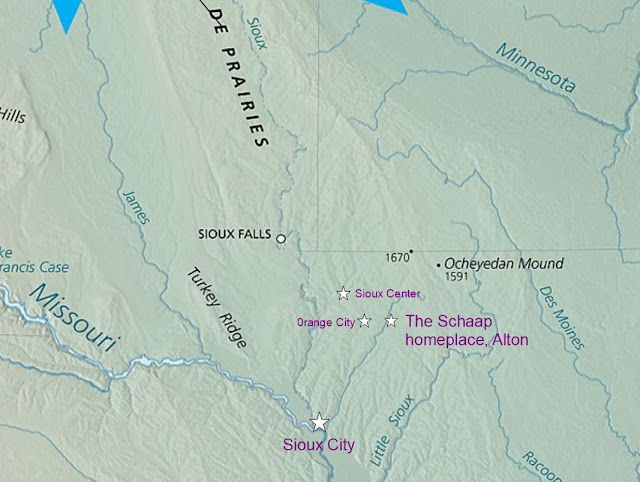

A couple of nights ago I stumbled on a French phrase that was new to me–coteau de prairies, a name given to a landform that doesn’t so much describe us–it’s a more clearly visible north of here–as it has come to define us, living as we do in its wash. Those two blue arrows designate lobes created long, long ago by a melting glacier, a space where a mighty meltdown split around a point of land that wasn’t inundated. The James Lobe–the blue arrow to the left–follows the James River Valley–“follows,” is deceptive: the James Lobe created the James River Valley, would be more accurate.

To the right lies the still distinguishable track of the Des Moines Lobe, which, as you can guess, formed the Des Moines River watershed. You may already have noticed that the divide at the northernmost point of the coteau de prairies, in far southeastern North Dakota (got to get there someday soon!) created a real parting of the ways because the James Lobe is Missouri River bound. It’s brother (or sister) is Mississippi River-bound; all of which makes the couteau de prairies more significant than it may seem if you’re trying to make good time to Winnipeg.

Today, the plateau–for that’s what it is, in a way–is home to innumerable wind turbines, and you can guess why. The wind–always blustering here–is most clearly distinguishable along the spine of this ancient land form. Hundreds of windmills churn out power that goes east, where it’s dumped into the grid that powers the east. Thank me when you turn on your computer.

Here’s a close up, along with some points of significant interest.

It’s a bit of a stretch, I suppose, to say we’re a part of the coteau de prairies. Chandler or Leota, MN or Bemis or certainly Sisseton, SD residents would likely mount some derisive laughter at my assertion. But we do garden in loess soil right there between the James and Des Moines Lobes. We are somehow recipients of what created the land form.

I don’t think it would have made any difference if I’d known all of this 40 years ago, when I moved to the southernmost limits of the coteau de prairies. Maybe if I’d grown up here, I would have heard about it, wouldn’t have had to stumble over it when I was almost 70. But I did, and at least I know now.

It seems to me there’s something scary about looking at maps like this, old maps largely a-political, maps so old they don’t distinguish a whole lot more than what the Creator has so marvelously fashioned. To know I’m part of what’s there and yet so foreign–it makes me feel kind of small.

And this one too–Lewis and Clark’s incredible attempt at mapping out a region known only to its strong aboriginal inhabitants. The Corps of Discover is trying to figure out just exactly where they are. And here we are again.

When Lewis and Clark left upriver, they called the place where they’d buried Sgt. Floyd, “Floyd’s Grove”–you can see it right above where I’ve located Sioux City. If you look closely, you’ll see the Floyd River there too, right now a frozen waterway a hundred yards north of where I’m sitting. And if you’re wondering about Prickly Pear River, so am I.

Of course, what the Corps of Discovery created on this parchment isn’t anywhere near to scale, but it’s marvelous anyway, isn’t it? What’s written in are the names they had and used for the region’s teeming first nations–Yanktons, Tetons, Ricaras, Sisatoone, Wapatoota.

It’s more than a little silly to think that when the Creator God looks down, somehow this is what he sees, something akin to Google Earth. Besides, we like to say he looks into all of our hearts, which makes maps beyond silly and God almighty a power beyond anything we can sketch out on parchment anyway.

A couple nights ago I stumbled on these old maps when I noticed that odd French phrase; and when I did, I stumbled, oddly enough, into my own world, as it is and as it was.

And at least for a while again, I felt deeply humbled because such spaces are huge and mighty, aren’t they? And somehow they have their own lives. It’s just plain daunting to see how this everyday world we know is someone else’s too and even something else altogether. Or was.

And still is, and forever shall be. Amen.