“Theologia crucis is not a single chapter in theology, but the key signature for all Christian theology.” – Jurgen Moltmann

The church staff I’m a part of is currently reading through the book Emotionally Healthy Discipleship: Moving from Shallow Christianity to Deep Transformation by Peter Scazzero (Zondervan, 2021). It explores seven key marks of biblical discipleship that, in Scazzero’s view, deeply transform lives.

One of these seven marks is “discovering the treasures buried in grief and loss.” Now it’s surprising enough that a popular book on church leadership and discipleship would mention grief and loss at all. But to lift it up as essential mark of the true Christian life is astonishing to me (in a good way!).

Scazzero acknowledges how much we avoid and deny pain and loss in our western culture, especially in our churches. In doing so, he insists that we miss “treasures of darkness and riches stored in secret places” (Isaiah 45:3 NIV). He suggests two primary reasons as to why we are so allergic to loss and grief: our resistance to losing control and a faulty theology that interprets losses as interruptions.

Scazzero prompted me to reflect on my own resistance to grief and loss, and I think he’s spot on with this fear of losing control and the functional theologies that shape our lives. The truth is, most of us want, to borrow Martin Luther’s categories, a theologia gloriae (theology of glory) as opposed to a theologia crucis (a theology of the cross). A theology of glory is about triumphalism, “up and to the right,” winning and success and getting want you want out of life. A theology of the cross, on the other hand, is a call to participate in Christ’s sufferings, to embrace pain and loss, to lose one’s life in order to truly find it.

In reflecting on all of this, my own faulty theology of “flourishing” has been exposed. When I was discerning God’s call to leave the church I had served for 12 years in west Michigan to return to my home in northwest Iowa, I remember saying to my spiritual director: “I sense God inviting my family and me into a season of flourishing. And northwest Iowa seems like a place for that kind of season.”

And yet the last four years has been a season filled with so much loss and heartache. There’s been joy, too–don’t get me wrong. But think about what the past two years especially have been like for all of us (and not just pastors). A global pandemic that has impacted everything and taken the lives of those we love. Racial justice tensions. A contentious election cycle. Polarizations over things like masks and vaccines. Denominational uncertainty. Members leaving and empty pews. And a host of other challenges that involve personal loss.

None of this has felt like flourishing. Just the opposite. Yet the strange gift in all of this for me personally has been the way it’s cracked open my theology of flourishing and revealed what’s really inside. Here’s what I’ve discovered (and I share it with some embarrassment): my vision of flourishing in life and ministry carries an expectation of the absence of pain and loss. Flourishing equals no hardship. No resistance. No suffering. In essence, no cross.

But is this really the biblical understanding of flourishing? A life free of struggle and pain? Can one flourish—experience wholeness, peace and joy—in the midst of pain? And through pain?

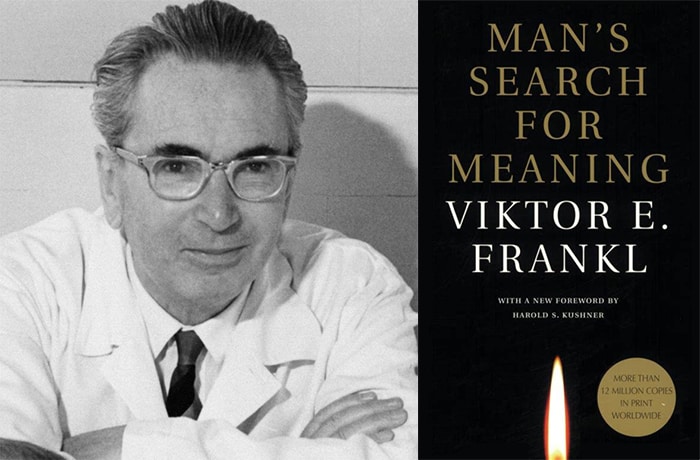

This summer I re-read Victor Frankl’s classic book Man’s Search for Meaning. It’s been decades since I read it last, and it resonated deeply with my heart in this season. Frankl, a Jewish psychologist, was among the multitudes carried off to Nazi death camps under the terror of Hitler’s reign. While in the death camp, Frankl observed two different groups of prisoners. There were those who were preoccupied with the question, “What do I expect of life? How can I change my circumstances?” They held out (false) hope that if they could just make it to Christmas, they would be released and reunited with their loved ones. But then Christmas came and went, and nothing changed. They fell into despair and died within days.

But there was another group that not only maintained hope amid such horrible circumstances, they even seemed to flourish (as much as one can in a concentration camp). The critical difference with this group, Frankl observed, was that their primary question was not, “What do I expect of life?” but “What does life expect of me?” And “If I can’t change these circumstances, who will I be in them?” They found an inner freedom and dignity that their oppressors couldn’t take away. They found a meaning in their suffering–a purpose greater than themselves, which led them to walk through the huts comforting others and giving away their last piece of bread.

Frankl concludes that our key task is to not avoid suffering but to learn how to suffer well. “His unique opportunity lies in the way in which he bears his burden.” A burden that one can only bear in a community of the cross. To bear this burden well—to bear it with dignity, grace, compassion and hope—well, that is a life of flourishing, at least until the kingdom comes in its completion when there are no more tears, no more pain, no more loss and all things at long last are finally made well.

Until then, let us take up the cross and follow the Crucified Lord who, for the joy set before him endured the cross for us all, disregarding its shame, and has taken his seat at the right hand of the throne of God (Hebrews 12:2).