I can think of two times in my life when teachers gave up on me.

One was during my time in Switzerland as a nanny. My work visa required me to take a weekly French class. One of the first days of class, the teacher wanted me to master a simple phrase—“J’habite à Crans” (translation: “I live in Crans”). She had me repeat the phrase over and over before throwing up her hands in exasperation at my clumsy midwestern tongue and moving on.

The other was several years ago when I won a few free personal training sessions at a gym. The young trainer told me to jump up onto a box.

“I can’t,” I said.

“Yes, you can!” he replied with great gusto.

I tried.

“Okay, maybe you can’t,” he admitted with a grimace.

I never became fluent in French, but I’m happy to say that, several years and a few trainers later, I’ve conquered the box jump. And I’ve learned the trick: it’s all about landing softly.

A soft landing means bending your knees and absorbing the impact rather than hitting the ground with straight legs and jarring force. While you work up the momentum and courage to jump, you also need to stay loose enough to land with some ease and flexibility.

Lately, I’ve been thinking a lot about the importance of a soft landing—especially when it feels so natural to brace for the worst. I’ve been wondering what it looks like to live in a broken world without becoming brittle.

It’s easy to succumb to living life on the defensive: assuming the worst about people around us, expecting to be disappointed, letting little things set us off on a path of destruction. Our neighbor is judging us, our co-worker is trying to one-up us, our community doesn’t care.

When we brace for the worst, we anchor ourselves to the ground—we forget how to leap. We lose the flexibility to breathe, to stay soft and open, leaving no space for grace, for compassion. For possibility.

Frederick Buechner, in Secrets in the Dark, says it this way: “Sometimes when we are alone, thoughts come swarming into our heads like bees—some of them destructive, ugly, self-defeating thoughts, some of them creative and glad. Which thoughts do we choose to think then, as much as we have the choice? Will we be brave today or a coward today? Not in some big way probably but in some little foolish way, yet brave still.”

I resonate with the notion that being brave can feel like foolishness. It means keeping ourselves open and whole-hearted, even as we understand that means we will get hurt. People will disappoint us. Our hearts will be broken.

Jumping might mean we fall more often.

And yet, the alternative is worse: always tight, always scared, brittle and cynical and certain that nothing good is possible. Tied to the ground, convinced that nothing can really be redeemed.

Just a few weeks ago, my father-in-law passed away and we celebrated his life. As we prepared for the vistation and funeral, we dug through boxes of old family photos. It struck me how much more grace we have for each other, for ourselves, in hindsight.

That photo taken during the family vacation—the one where Uncle Mike had his eyes shut, Joey was pouting in the corner, the baby was crying, and we were all sweaty because of the humidity. And wasn’t I tired and a little ornery from sleeping on camper mattress that felt like a slab of plywood all week? Now, it’s a treasure—a gift. Its imperfection is what makes it moreso.

In hindsight, we often discover the mercy that can be difficult to summon in the moment. With time, we find a bit of the softness our present-day hardened hearts resist. The things that once annoyed us become endearing quirks; some of the hurts loosen, others quietly dissolve. We begin to see that we are all imperfect people, often doing the best we can with what we’ve been given. Created in the image of God, yes—but living a life that is messily human and beautifully unfinished.

I was recently in a middle school sharing about my book, Enemies in the Orchard, when a 7th grader asked, “But, like, what’s it really about?”

I struggled more than I should with that question because it’s easiest to respond with a pat, moral statement: “The story is about really getting to know people, especially those we’ve been preconditioned to hate, before we judge them.”

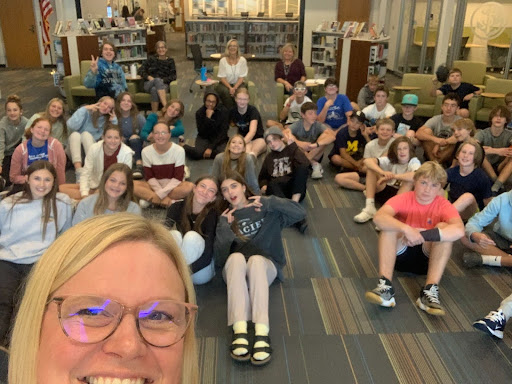

I’m still asking myself days later, how, in that crowded library with a bunch of 13-year-olds sitting on the floor—some listening, some daydreaming, some distracted by the friends sitting around them—I could have better summarized a story that what took me hundreds of pages to tell.

If I had a do-over, I might say: “I was trying to tell a story about World War II—but even more, a story about our human tendency to expect the worst from people. A story about harsh world leaders who tricked a generation into believing that power, greed, wealth, dominance, and striving for excellence were better than openness and vulnerability. And they tried to make the kids believe that, too. They tried to convince teenagers like you that armoring up and telling yourself you’re better than anyone else, that being tough and strong would somehow keep you safe.

But the truth is, we’re going to get hurt, we’re going to suffer more when we open up to others, when we let our guards down, when we choose to live less defensively, more open to grace and suprise. And yet—doesn’t that still seem so much better than the alternative?”

But alas, I’m more of a writer, a wrestler with words, than a polished presenter and I babbled through something that I hope, at the very least, sparked a few more questions, encouraged them to read, to wonder, to be curious about the stories and people around them.

But unlike my French teacher, I’m not going to throw my hands up and storm away—I believe we can learn and unlearn what the world tries to convince us. We can hear the quiet of God’s voice over the loud lies of fear and self-protection. I believe we are called to more than expecting the worse.

Every day, I grow a little older—and while I know I won’t be leaping onto boxes forever, I don’t want to get stuck, bracing for impact, brittle with fear and cynicism. I pray for the courage it takes to fall softly.

5 Responses

Beautifully expressed. Thank-you.

The concept of landing softly as you develop it has a lot of really important applications to my life these days! I pray for “the courage to fall softly.” Thanks so much!

Lovely. Wise words–I am thankful that you are using your gifts, landing softly, humbly learning and unlearning when necessary. Thank you.

Dana,

You landed it, ever so softly, ever so gently convincing.

Thank you

Dana, your Landing Softly was aptly timed for this day when a number of CRC clergy and congregations in Grand Rapids will be officially disaffiliated from the CRC denomination.

That makes me think of being shoved out of a flying airplane by a crew that says “Get out, you don’t belong with us anymore.”

Gratefully, a Parachute has been divinely provided to insure a “soft landing.”