It happens in cycles, this nostalgia for the past.

I remember wearing some flare leg jeans and my mom remarking that she wore something similar in the 1970s. To be fair, digital age trends rise and fall so quickly now that it’s hard to discern the significance and length of something to be deemed a trend.

The early aughts (early 2000s) seem to be trending, especially among American youth. As a millennial who has young kids and teaches college students, this focus on the early 2000s is as perplexing to me as my interest in the 1970s fashion may have been to my mom in the late 1990s.

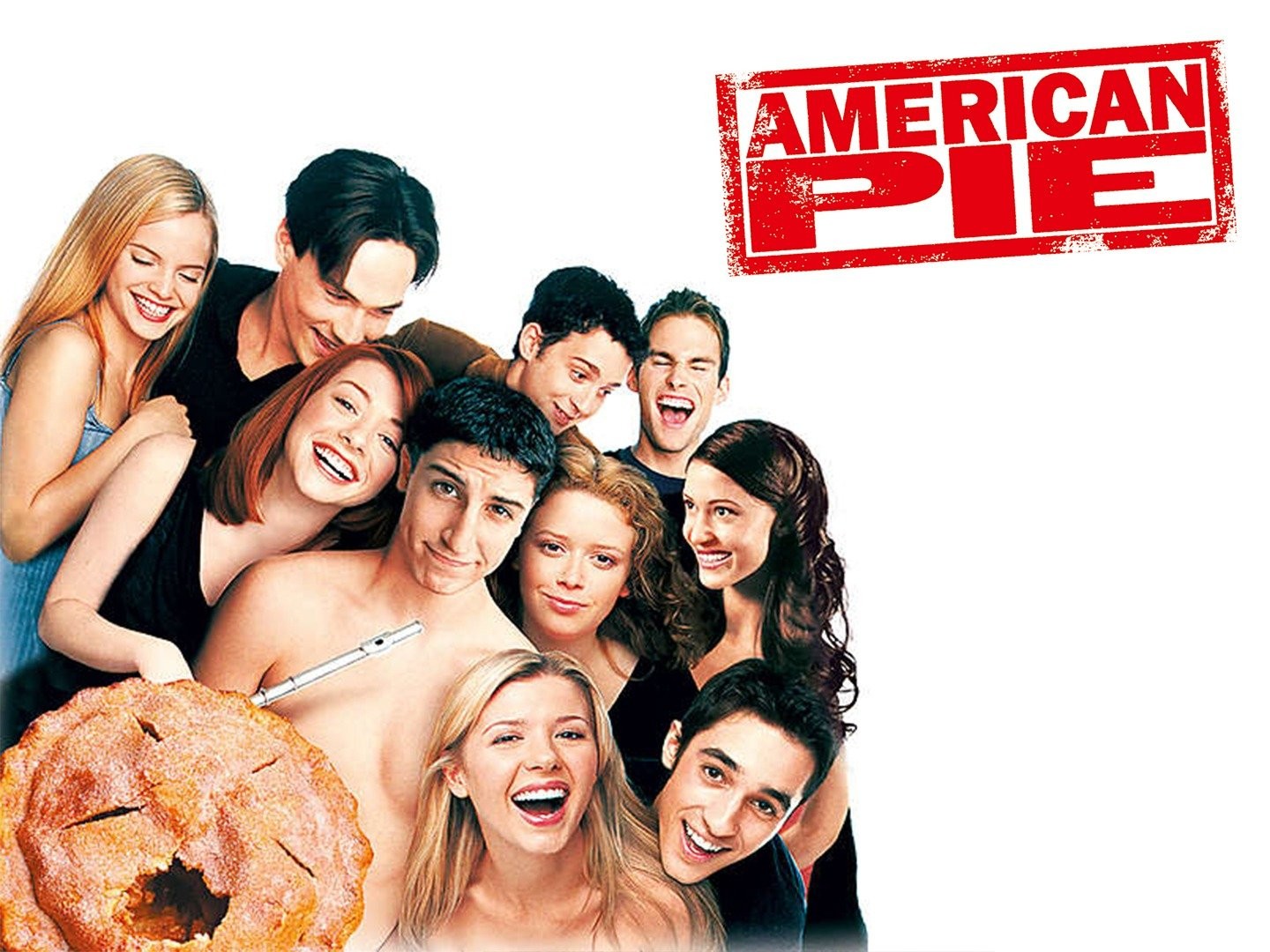

As a teen and young adult, I realized I did not like the late 1990s versions of popular comedies. With a few exceptions, I found the cultural conversations around American Pie, and all the teen, frat-boy humor comedies that followed that film to be, well–ridiculous and not very funny at all. There were more than a few instances where I voiced my opinion about this and I was dismissed as prudish or someone without a good sense of humor. As someone who has always loved a fart joke and thought I did have a good sense of humor, I was puzzled.

So I avoided the frat boy humor marketed as rom-coms and kept my opinions mostly to myself. And yet I wondered–popular film after film had the same premise: young men behaving poorly, but claimed as lovable and good if they managed to get a hot, one-dimensional woman to love them.

Growing up in both Christian and 1990s American culture, I noticed my youth pastors and youth leaders talking about living a Christ-like life and how to cultivate the fruits of the Spirit. But they also talked about how great marriage was and celebrated the hotness of their wife. Was this just a cleaned-up, Christian way of doing American frat-boy culture?

Sophie Gilbert, writer for The Atlantic, and author of the new book Girl on Girl: How Pop Culture Turned a Generation of Women Against Themselves, understood the message of the 1990s this way:

What was obvious to me was that power, for women, was sexual in nature. There was no other kind, or none worth having. More crucially, the kind of power being fetishized in popular culture on the cusp of the twenty-first century wasn’t the sort you accrue over a lifetime, in the manner of education or money or professional experience. It was all about youth, attention, and a willingness to be in on the joke, even if we were ultimately the punch line.

There was a movement in the 1990s toward feminism’s third wave, a movement that tried to be more inclusive, sex-positive, and more hopeful about the future. But 1990s mass media culture worked to define feminism as an individual choice instead of a collective and all-embracing. Again, Gilbert, “instead of an inclusive movement that acknowledged intersections of race, class, and gender, we got selective upward mobility and rampant consumerism.” And it was consistently sold to American girls and women as empowering.

Gilbert cites Natasha Walter’s book, Living Dolls, that media “co-opted words such as liberation and choice to sell women ‘an airbrushed, highly sexualized, increasingly narrow vision of femininity’–one in which we were expected to choose a life of being both willing objects and easy targets.” Gilbert explores the music scene, the influence of the porn industry on film and fashion, the representation of fighting women on reality television, and the role of diet culture and the makeover industry. She also explores the role of the girl boss.

Enabled by social media and Instagram in particular, women “rapidly figured out all the ways in which they could turn the art of self-presentation into a lucrative side hustle.” Gilbert ends with a study of the women of power in our culture and they ways women are treated, discussed, and portrayed.

I am still chewing on Gilbert’s analysis. She is, of course, looking at our current cultural reality of 2025 and looking to the past to explain how we got here. As a teen and young adult, I didn’t thoughtfully analyze the 1990s cultural messages, but I certainly received those messages. In 2025, I see the current tradwife trends and the early 2000s nostalgia trends as, perhaps, ways to grapple with these troubling messages of masculinity and femininity that we received in the late 90s and early 2000s.

In the meantime, cultivating the fruits of the Spirit remains a humbling and worthy pursuit.

2 Responses

Amen. Thanks for your reflections here.

American Pie is a bad movie that does not cultivate our better angels. But it was nearly required viewing for West Michigan kids born between 1960 and 1980. The writer, Adam Herz, was a graduate of East Grand Rapids High School (East Great Falls in the movie). I met Mr. Herz’s father once, a venerated neurosurgeon at Blodgett Hospital. He bears a bit of a resemblance to the protagonist’s father, played by Eugene Levy (more famous as the dad in Schitt’s Creek). The lacrosse game in the movie was the blue-gold East Great Falls against their green-and-white clad arch rival “Central” (Forest Hills Central), a 50-year rivalry among wealthy schools that still exists. Other regional references include Dog Years restaurant (Yesterdog located on Wealthy Street), and renting a summer cottage in Grand Harbor (Grand Haven) on Lake Michigan after their first year of college in American Pie 2. Of course, none of it was filmed locally, but lots of regional references.