It began serendipitously with an email I wasn’t meant to get.

A long-ago neighborhood friend I hadn’t seen for seventy years, and with whom I had corresponded only occasionally, would be passing through his old Michigan haunts on his way to Colorado. Might a few of his high school friends, he wondered, be around for an evening?

I wasn’t one of them, having left our shared community when I was only eleven and he only five, but I had somehow popped onto his email list. Still, we agreed when I wrote him back, why didn’t we try to meet up as well and roam a bit through our old terrain and our collective memories? And so we did on a recent Sunday afternoon.

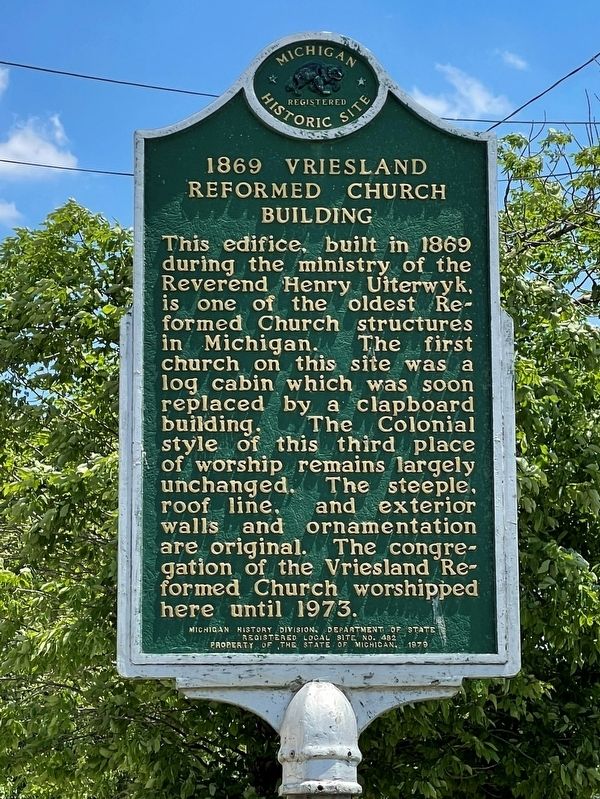

constructed in 1869

We met in the parking lot of the country church on either side of which we had lived, my father the pastor and his the part-time janitor. Tree-climbing being the soul of youth, the conversation turned quickly to remembered trees. The beloved mulberry tree in back of his house was no longer there, but the horse chestnut tree next to the house still was, having now grown enormous, its yearly time of white, foot-long clusters of spring blossoms apparently just past, but promising more than we had ever known of those green, spiky autumn capsules that made a mess of the ground and we split open for the conkers inside. That landmark beech tree a mile or so away in “Doc’s Woods” was still there too, my friend had assured from an earlier visit, a gnarled, much-initialed eminence in what is now a public park named for the Van Zoeren family, longtime local residents, one of them a building-named donor to Hope College.

Not, of course, to forget the allurements of a different order provided by “Fred’s Dump,” that smelly sprawl of scavenger promise to the east, also named for the person on whose farmland it lay. And what about our memories of those surreptitious trips—first crouching, then crawling—through that culvert under Byron Road and finally, after a righthand turn, coming blessedly out at Hank Van Haitsma’s pond, our early lesson in looking for light at the end of the tunnel?

And, speaking of streams, what about our summer-afternoon cane-pole fishing in “Swamp Ditch,” just to the west of town, the muddy stream home to numberless shiners but also to the (very) occasional lunker carp, no thing of beauty but providing a bobber-diving jerk and pull thrilling enough?

The donum superadditum of our Sunday rendezvous was an unexpected tour of the house in which I had once lived, now no longer a parsonage but privately owned. Would we like to come in, the owner asked, when we encountered him in his backyard and I explained our intrusion. Indeed we would, and he and his wife, to whom he quickly introduced us, seemed as eager as we to learn what might have changed over the decades. Very little, I was delighted to see.

That enclosed but unheated front porch on whose imagined runways my model DC-3 had made so many hand-held landings was still ready for any boyhood flight. And, yes, those grand, oak pocket doors were also still sliding smoothly on their rails, one of the doors closing off what had been our “Music Room,” so named for the Steinway upright on which my father picked his way through Beethoven sonatas and on which my own lessons were already offering little promise of a concert career. The “Music Room” was also the family room, in which, on a week night, the Arvin table radio brought forth the Lone Ranger galloping up on Silver, his “fiery horse with the speed of light,” and on Sunday evenings, at sabbath close, the domestic joys of Fibber McGee and Molly and the stentorian reassurance of Mutual Broadcasting’s Gabriel Heatter: “There’s good news tonight!”

The church across the parking lot—connected in my time to the “Music Room” with a transmission line and a single earphone rigged to enable my weekend-visiting grandmother to hear her son preach—was built in 1869, the third edifice (after a log and then clapboard structure) of the Vriesland Reformed Church. Now occupied by the Zeeland Church of God, the building still stands white and tall over whatever the intervening developments in the countryside, a registered Michigan Historic Site visible from the I-96 expressway.

The church’s founding Frisian congregation, part of the 1834 Secession from the established Dutch Reformed Church in the Netherlands, had formed in October of 1846 in Leeuwarden with the express purpose of immigrating to America. The first contingent of twenty families and thirteen single persons, accompanied by the Reverend Marten Ypma, left from Rotterdam on April 7 of the following year, and arrived in Holland, Michigan, in June. A smaller Frisian contingent left six weeks later from Amsterdam, followed eventually by groups from Flakke, Gelderland, and North Holland.

The first wave had arrived in the Holland area at approximately the same time as a contingent from Zeeland, whereupon an amicable agreement was made that the Zeelanders would settle to the west of the aforementioned swamp and the hardy Frisians would farm the clay soil to the east.

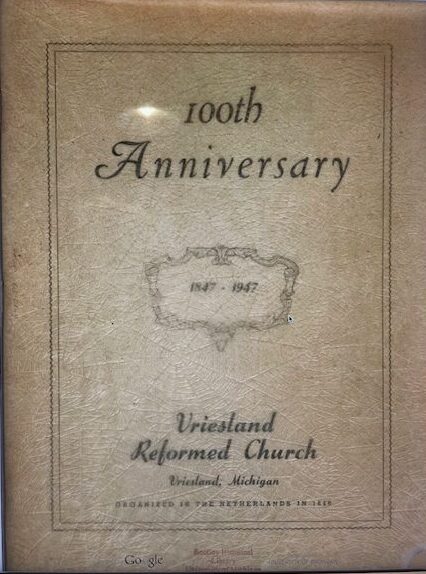

1810-1863

In their first year, according to the 100th-anniversary volume published by the church in 1947, the Vriesland community endured much suffering and death. Twenty-seven members died, including three entire families. The Reverend Ypma suffered with them, receiving no salary, his only income coming from whatever preaching he did in Grandville and Grand Rapids. “Many were the times,” says the anniversary history, ”when he walked to Grand Rapids,” nearly twenty-five miles each way. And during his five-year Vriesland pastorate, until he left in 1852 for a church in nearby Graafschap, he and his wife lost their only child.

My memories of this church are idyllic—bespeaking, no doubt, the innocence of youth but also a sunnier and more stable time. Paging online through the anniversary book again after the many years was a delight. There on page 10 is the 1947 Consistory I could in almost every case still identify by name, a uniformly arms-crossed block of rectitude and formality whose suits and ties belied their bib-overalls weekday work on tractors and in the barn.

And there on page 35 at the organ console, looking as regal and accomplished as I remember her, is Ms. Eileen Schermer, daughter of my beloved elementary school teacher and already at nineteen or so on her way to a long and distinguished career of her own as an elementary teacher. She was named, I see from her obituary, Michigan Rural Teacher of the Year in 1956. And, not to miss the fun, there on page 28 is the full church sanctuary with its rear gallery, the ideal height from which to launch a paper airplane during Sunday School while David was busy with Goliath.

Humor, but enduring poignancy too. There, on page 39 in the front row of what would shortly become my own Sunday School class, sits Freddie Ter Haar, tragically killed only two years later by an automobile on M-21, all we elementary school classmates led sensitively and solemnly across the road from the Vriesland Public School to pass his coffin in the church. Sad loss, too, was to be gently but sturdily acknowledged in the nurture of the child.

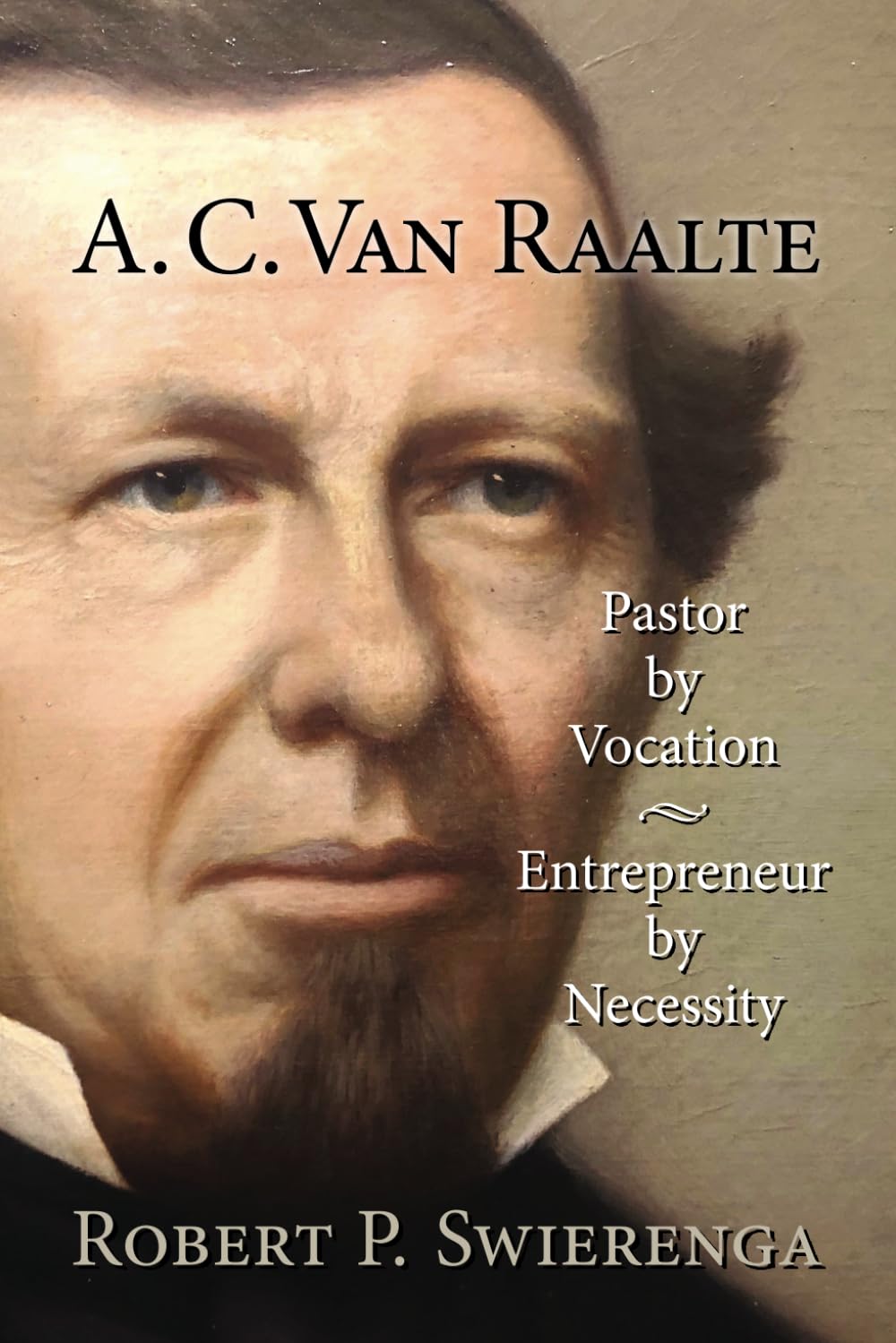

But whatever the recollected stability and tranquility of my own country life, to know the story of the Vriesland church is to know also its part in the factionalism and schism in the early Midwest Dutch settlement, beginning with the 1834 Dutch Secession itself and the subsequent migration. As Robert Swierenga puts it in his definitive and handsomely written biography of A. C. Van Raalte, founder and leader of the Holland, Michigan, Dutch Kolonie,”conflict came in the baggage of the immigrants.”

Having left an established Dutch Hervormed Kerk they thought had strayed from true faith and piety, many of the immigrants were almost from the start wary of their Dutch Reformed compatriots who had been in the East since the time of Peter Stuyvesant and the Dutch settlement in New Amsterdam and had formed what came to be called the Reformed Protestant Dutch Church (RPDC)—eventually, in 1867, the Reformed Church in America.

This Eastern church, under the leadership in particular of Isaac Wyckhof, wanted to reach out to their newly arrived kinfolk in the Midwest, and Van Raalte and others were eager for their support, especially financial, in a community struggling to create a new life in the wilderness. Wyckoff traveled west to Holland, even riding out on horseback to the neighboring villages like Vriesland.

In 1850, Van Raalte, in a decision reached mainly with fellow clerics rather than parishioners, formally affiliated Classis Holland, including the outlying towns, with the Eastern RPCD. The decision was arguably premature. Already by 1853, complaints were arising in the Kolonie that the theology and practices of the rapidly Americanizing Eastern church—among them failing to preach regularly from the Heidelberg Catechism, substituting mere Sunday school for rigorous catechetical instruction, singing humanly written hymns rather than strictly the Psalms written by God (some of these hymns, moreover, tainted by revivalist Arminianism), and countenancing membership in Masonic lodges—reflected more the slippage of mainline American Protestantism than the faithful church they had wanted to be in the face of the established church in their home country.

And thus was born, in 1857, only seven years after the union with the RPCD, yet another secession, this one forming the True Holland Dutch Reformed Church, to be merged in 1890 with the True Dutch Reformed Church, an even earlier dissident group that had left the RPCD. The result of this 1857 merger was the Christian Reformed Church.

The Vriesland consistory had affirmed Van Raalte’s 1850 union with the RPDC, but its congregation, too, included members with misgivings about the Eastern church and its ways, the winds of skepticism fanned by Gijsbert Haan, a polemical Vriesland elder who had come from the dissident True Dutch Reformed Church in the East and was bent now on bringing the same criticisms of the RPDC to bear in his new setting.

From Vriesland, after three years, Haan moved to Grand Rapids and continued his anti-Van Raalte critique from there. Though in the company other strong voices, Haan is often thought of as the father of the CRC. In the end, the dissidents in the Vriesland Church largely assimilated into the staunchly Christian Reformed Church in neighboring Drenthe, a few miles to the south, making for what I remember as a kind of twin cities of the Dutch Reformed tradition, RCA to the north and CRC to the south.

Against this complicated backdrop of Reformed schism, the Synod of the Christian Reformed Church will meet this week after yet another disaffiliation, that of CRC churches who could not in conscience accept the rulings of recent synods on human sexuality. An outcome for me, as a longtime CRC member of one of the disaffiliating churches, may turn out to be that in my older age I will come full circle and rejoin the denomination of my remembered boyhood of seventy years ago, a small irony that comes to mind now as I reflect on a recent Sunday afternoon.

11 Responses

My goodness, what a history to be gifted to read. This Sunday morning in the year 2025 when humans Dutch and not are wrestling still with the angels of how to make meaning among ourselves and others. Sending mighty thanks.

Thanks, Jon. This touching, beautifully written tribute captures the courage, devotion, and sheer bullheaded determination of those who came before us.

Small irony indeed! Loved the walk through your boyhood memories as well. So much forms us without our realizing it until much later. A gift that you could be reunited with your friend.

Beautiful reminisce of a time past, reminding us that it seems to be in the nature of our species to repeat the past in our quest for the ‘perfect’ whatever. Our inability to stay in unity reflects the broken nature of our world and ourselves. Thank you for the irony of much of it.

Thanks, Jon. A fascinating—and sad—bit of church history of mid-19th century schisms. The ironies continue. Both the CRC and the RCA have recently gone through schisms, the CRC over the ordination of women and the RCA over human sexuality. And now, after Synod 2024, the CRC is in the process of enforcing another schism in effect, church by local church, member by individual member, many of whom, like you, are joining the RCA. It appears we never learn from history.

Yup, Hugh… And thanks, Jon, as usual when you write. Please do so more regularly, OK?

I recently found a copy of the 100 year history you referenced. I’m happy to give to someone who would like to read it.

Thanks for this look back in time. As soon as I saw the picture of the parsonage, I immediately recognized it as the Vriesland parsonage. I grew up in Drenthe, two, miles south, but much of what you recall in the area is familiar to me. Also, Freddie Ter Haar was my cousin and I well remember that sad time.

Lynn,

I’d like to borrow that history. I was baptized in the Vriesland Reformed Church. The places name brought back happy memories.

Judy Parr

The pesky 5-year-old pipes up:

Jon, for those few hours together on that blissful Sunday afternoon we were young again, prowling the fields and woods and gullies (and the dump, of course) of Vriesland in the late ‘40s and early ‘50s. There were Frank’s plums, the carving of whistles from basswood twigs, pheasants, softall in the Drenthe grove, the two-room school house, and so much more. The more I reflect on those early years, the more special I realize they were.

Next time we will visit the cemetery. My great grandfather arrived in 1848, from Friesland in the Netherlands, settling of course in Vriesland Michigan, and he’s buried there. You’d recognize all the names there, too. You once wrote eloquently (redundant adverb) about how an interstate now separates the church from its cemetery, a symbol of “progress.”

Here’s more progress: Would you believe, that 100th anniversary volume celebrating Vriesland church is available from Amazon, for $23.99, printed on demand in Delhi, India! Leather bound, no less.

Go Vriesland!

Jon, Thanks as always from your wisdom , perspective, and such well-crafted writing. I just read a FB reflection from an RCA observer at current CRC Synod, where delegates declared that the “Pella Accord” was dead. A few remembered that this came from the joint CRC-RCA General Synod(s) which the late Peter Borgdorff and I managed to organized, and included some moving moments of painful memories and mutual confession. The Pella Accord was modeled on the Lund Principle, an ecumenical agreement in the 1950’s written in Lund Sweden, and unknown I’m sure to 99% of those in Pella, which stressed doing together all things possible except when “conscience” might prevent. We thought it was a modest step forward of healing from the legacy of dynamics described so well in your piece. But today, the voices which have prevailed, and the mood of mistrust and recrimination, echoes the stories which you recounted. The coming together of many CRC folks, like you and COS, leaving the denomination over their “conscience” and perhaps joining the RCA is warmly received by those like me, and yet, full of irony, heartbreak, and broken hopes.