Not from the “American” pope, Leo XIV, but from his recently departed predecessor, Francis I. We all need some hope these days. Certainly, I do.

For me last week started with a five-alarm fire at Calvin University set off by the Christian Reformed Synod of 2025; should the blaze go unchecked, it will ruin much of what has made Calvin worthwhile as a center of learning. The week ended with the president of the United States recommitting the country to war in the Middle East for little more reason than his need to get in on the cool optics of Israel’s assault on Iran.

In that mood I noticed the title of Francis’s autobiography, Hope.

Hope in the Face of Evil

Hope needs a lot more grit than mere optimism because, unlike the latter, it registers the full scope of pain and evil in the world. Francis’s family history put poverty and war front and center. His grandparents were among the hundreds of thousands of Italian immigrants who fled to Argentina from the hopeless economy and fascist aftermath of their country’s foolish, feckless participation in World War I. Unlike some, Francis’s parents did not pull up the ladder behind them but instilled in their son a deep compassion for all subsequent immigrants, from whatever quarter. As pope, Francis preached that message tirelessly around a world facing an ever-rising tide of refugees.

As in his grandparents’ case, the refugee tide is redoubled by wars within and between nations, and Hope reverberates with denunciations of their folly, waste, and futility. Francis walked where he talked too, visiting the killing fields of Sudan, the Congo, and Palestine, while bearding the Russian ambassador in his den to press for Vatican mediation of the conflict in Ukraine. That none of this “worked” did not negate the importance of his witness, Francis insists. It was listening to the victims of war, encountering their pain in the flesh, showing tenderness up close and personal that models the change of heart that can alone break the chain of violence.

The Teachers of Hope

A very hopeful scenario, flying in the face of “reality.” Where can this hope be grounded? How can it be nurtured and spread? For that matter, what are its essential ingredients? Francis lays out his answers one by one, tracing the development of Jorge Mario Bergoglio from the barrio of Buenos Aries to a priesthood in the Jesuit order to an ascending scale of offices in the church. The offices as such he dismisses; it’s the work one can do in them that counts—teaching high schoolers, helping fellow priests, giving pastoral counsel, and always, always keeping the poor foremost.

Likewise, it wasn’t the curriculum as much as the teachers and mentors that made his education, and these came from the humble more than from the learned. His grandmother and sister. His parish priests. His neighbors. The nurses who tended him through grave illness. Above all, the radical and non-believer Esther Ballestrino de Careaga who led a massive protest by mothers against the Argentine dictators’ practice of “disappearing” dissenters. Again, apparently futile—Esther herself was swept away—until the dictators themselves were overthrown.

The What and How of Hope

From this saga we can glean hope’s core ingredients and preeminent fruits. Besides the above-mentioned compassion, sympathy, and tenderness, there are the predictable humility and gratitude but also the less predictable humor, play, and joy. Above all, the art of listening and the practice—and acceptance—of forgiveness.

The list adds up to a (1) deep trust in God as ever present, ever welcoming, and ever loving, and (2) persistent attention to our neighbor, all our neighbors, as children of God, however far they may have wandered from the paths of piety or propriety. Those last two are not the same, Francis repeats by means of many examples, poignant, hilarious, and sad by turn.

Where and how are these nurtured? In the church, and more often by its ordinary members than by its officials. Francis’s pages persistently jab at clericalism as well as at the sticklers for traditionalism who mistake it for orthodoxy. (“What’s the difference between a terrorist and a liturgist,” he recalls Archbishop of Canterbury Justin Welby joking. “You can negotiate with a terrorist.”) A church that remembers it is God’s house and not man’s (gender specificity intended). A church that therefore has room for all, including the divorced and non-heterosexual. Likewise, a church that is frankly “female,” that—as in his own life—having derived abundant wisdom from women, gives them more roles and rostrums. (177) You see why Catholic theobros like J.D. Vance and Ross Douthat got their Jockeys in a twist over the man.

Hope for the Newly Homeless

So what are the messages that the readers, and the obsessions, of this blog can hear from Hope? Let’s put Francis in the role of John at the beginning of the Book of Revelation.

To the angel of those disaffiliated from or disillusioned with their native denomination write: yes, discard traditionalism but hold fast to tradition, for people without roots tend to be “sick” and “lost.” Roots give “strength to move forward, to bear fruit, to blossom.” (11) Citing Gustav Mahler: “Tradition is not the worship of ashes, it is the reservation of fire.” (91) For only by—but then necessarily out of—memory can we muster “courage to open new spaces to God.” (114) In a word, “tradition means moving forward.” (203)

Hope for Calvin University

To the angel of Calvin University write: “to educate means ‘to love the questions’ [Rilke], to let them live, to let them wander. Those who are afraid of questions are afraid of the answers, and this is the characteristic of dictatorships, of autocracies, or of empty democracies, not of free children. To educate is not … to deliver a pretty parcel tied up with a ribbon with a message saying: ‘Please keep this exactly as it is.’ Instead, it means … to transform dreams that are received, to carry them forward, and to dream them again.” (272-73)

Hope for the CRC

To the angel of the Christian Reformed Church write: “To confuse unity with uniformity is a diabolical temptation.” True unity is “reconciled diversity.” (46) Remember that “God forgives with affection, not by decree. If the Christan wants everything clear and certain, then he or she will find nothing. … Those who are always looking for solutions through regulations, who tend toward doctrinal ‘certainty’ … have a fixed and inward-looking vision” that turns faith into “just one of many ideologies rather than a living experience.” [114]

Hope for Donald Trump

And to the angel of Donald Trump write: bad news, compadre. That ingredient list above describes the exact antithesis of your character. More dangerously, your narcissism makes you not a “sinner” but one of the “corrupt people” closed in on themselves and thus closed off from the possibility of salvation. (115) Further, you could hardly help but go to war for, befitting your character, “war is not only a spectacle of lies—since it is always preceded and accompanied by lies”—but “war is a lie in itself.” (245)

Further yet, oh you without humor: where there is no laughter there is no genuine humanity but what Argentinians call “zizzanieri”—people who “move about in the shadows and spread the poison of malice and gossip,” multiplying “the evil from which they themselves suffer. They are people without hope; they are desperate people. And desperation doesn’t laugh, at worst it mocks….” (266)

The angel now looking up at America continues: mockery “is none other than the thermometer of a society that is depressive, self-destructive, that feels the need to destroy more than it builds, to encourage the instinct to die rather than enjoyment of life.” (267)

Hope as a Little Child

Choose instead, Francis enjoins, to follow “that steadfast lively child” (267) memorably portrayed by Charles Péguy in The Portal of the Mystery of Hope. Her name is Hope, and she scampers around the room unseen by busy adults but turns out to carry the day. And true religion as well. Faith and charity only see and love “what is. But she, she sees and loves what will be.” (254)

That little one “was my playmate as a child,” Francis concludes. “As an adult, on several dark days I lost sight of her” and thought she had “abandoned me, but it was I who had lost sight of her; and then I promised once more that I would follow her forever; because her heaven is already on earth.” (267)

Header photo by Ashwin Vaswani on Unsplash

18 Responses

BRAVO!!

Thank you!

Ah, James, thank you for this prophetically hopeful piece! And a bit of humor too.

Wow! I’ve read this over twice now and have tears in my eyes. I so appreciated the sharing of the little child called Hope who in the end turns out to carry the day. If she was Francis’ childhood playmate and stood by him all through his life, even though he on dark days lost sight of her occasionally, I so wish I could claim such familiarity.

Thanks, Prof. Bratt, for your words and for reminding us about where Hope might be hiding in plain sight. And thank you, Francis, for your example of how to lead a Hope filled, Heaven filled life!

I’m buying the book.

Right on! I was reading the NY Times this morning and finally quit, clicked, scrolled down and found you. What a compass to right my course! Thank you for being God’s mouthpiece.

Thanks, Jim. As always this is great.

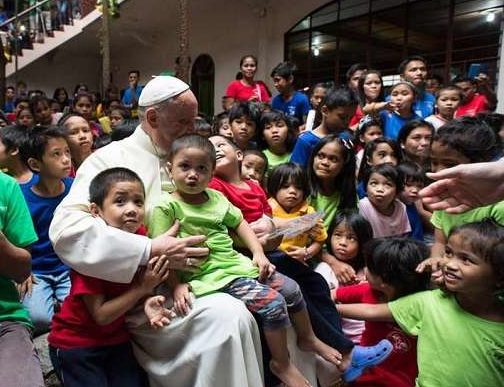

Sorry for this personal comment, but… I have to mention that, back in January, members of my family experienced the delight of meeting Pope Francis and seeing his delight with children.

Our son works in London, where he heads the office of Faith and Unity at the Anglican Commuinion main office. As such, it was part of his job to accept an inviatation to Rome during the Week of Christian Unity, at the end of January. Because he was offered a nice accomodation, his wife and 18-month-old daughter accompanied him. They were invited to the audience with the Pope, attended by hundreds of others.

Everyone was seated, mostly dressed in clergy black, or for non-clergy, dark suits or dresses. All expect my little granddaughter, Elizabeth, who was there in a white dress. When Francis came in on his wheelchair, he spotted the baby, who stood out in the sea of black. The Pope headed right over to her, and spent some time interacting with the family. Then he put his hand on Elizabeth’s head, and gave a personal papal blessing. Someone took a picture that will be a treasure in our family. But for those who were present, it was inspiring to witness Francis’ enthusiam with children.

Beautiful. Just what I needed…

Good for my soul and mind. Thank you.

Thanks, Jim.

Insightful and timely reflections.

For more on ecological hope (and courage),

see chapter 5 of my book “Earthkeeping and Character.”

Thank you, thank you, thank you for your (no, Pope Francis’) words of hope. I needed them. We all need them. I “hope” many are listening.

To the Angel of Calvin University write: Build more dormitories. Build more dining halls. Blessing and prosperity is coming, if you embrace my Word, seek Truth, and extirpate the old, decadent, foul intellectual rot. Compel the employees there to turn from their silly ways and ideas. Let their gravamina be smashed against to shoals of Truth, and let the lifeboats of orthodoxy bring them safely back to the shores of East Beltline. And, one more thing, go back to Calvin College.

Marty Wondaal, My ears are hearing, there is no reasonable explanation for me to believe that this tirade was heaven sent.

Trynette Brander

Protestant hope in Protestant (!) Pope.

is this truly a Reformed,Calvinist Journal?

what a laugh.

Andreas, your reply highlights the current divide in the CRC, some, like the author of this article believe truth should be embraced wherever it is found, this is part of having a liberal arts education. Others close their ears to anything outside of their inner circle, they prefer walls to bridges. To think that folks from one of the smallest and least influential denominations could not learn from the head of the largest, is scary at best. And don’t forget, one of the last things Jesus stressed both before his death and again to John on Patmos was that Christians need to stay together, they will know we are Christians by our love. If there was something in the article you found to contradict Jesus, point it out, if you have nothing but want to slam it anyway, attack the person.

Jim and Dan,

Well said. Thank you both.

Jim, Thanks for this timely blog. It’s a depressing time to be CRC and experience the thoughtless demands of the current “leadership.” I’m committed to LaGrave where I am nurtured and feel God’s love. I have no need to be part of the CRC. Please keep up your good work!