It’s time for another edition of books I just can’t stop talking and thinking about.

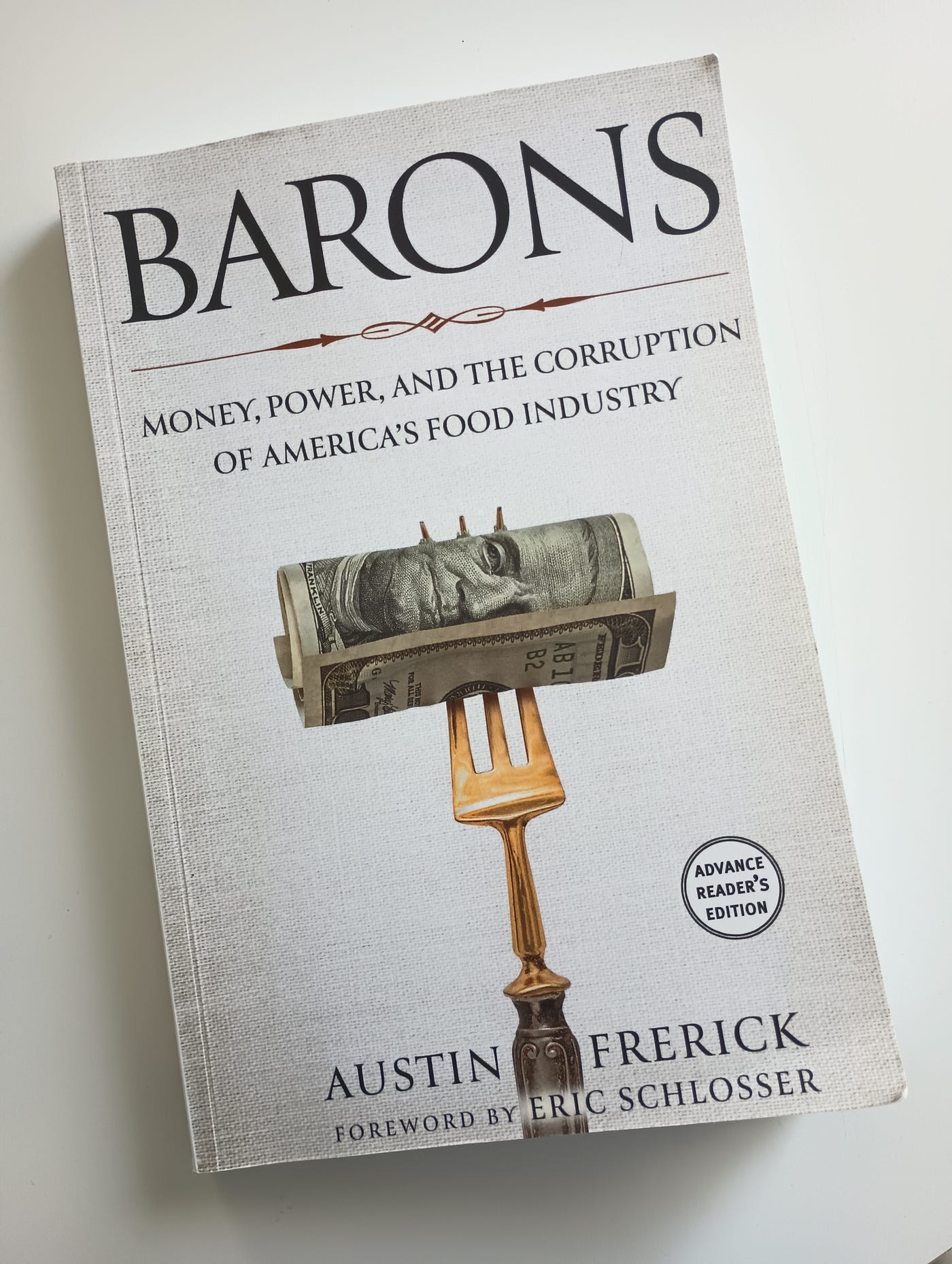

This month that book is Austin Frerick’s Barons: Money, Power, and the Corruption of America’s Food Industry. I may be a bit biased–it’s always great reading a fantastic book written by a fellow Iowan–but Frerick’s account of the American food industry and the few wealthy families and individuals that control large portions of it might be one of the best books I’ve read so far this year.

In the book, Frerick uses seven “titans of the food industry” and the respective sector they control as case studies to examine the way unchecked power and greed corrupt the system and harm the vast majority of Americans.

There is a chapter on the Driscoll’s berry empire, on Walmart, on Fairlife milk, and on various families involved in the meat, grain, and coffee industries. The book addresses industrial farming, consumer choice, government regulation and its limitations, economic inequality, labor issues and working conditions, the struggles of rural communities, and much more. For a short text (only about 200 pages), Frerick packs so much in.

The book traces how each of the tycoons that Frerick chose as case studies took over their respective industry and the fallout of a single entity controlling such a great proportion of our food system. Frerick also exposes the ways these wealthy individuals and families exploit their workers, the environment, consumers, and the economy to grow their wealth.

For example, he details how the hog industry has poisoned many of Iowa’s waterways. And how the berry industry in California uses so much of the state’s water supply. In many of these industries, wealth is created for those in charge on the backs of exploited workers who are working in horrible conditions. Tycoons gut rural areas and small businesses to solidify their control of the food industry and further enrich themselves and their stakeholders.

As a Midwesterner, I appreciated his deep dive into the impact of these industries on their local communities. Frerick, himself an Iowan who still has family connections in the state, has a way of bringing that local impact to the forefront of his analysis throughout the book, and when it’s relevant, references the many ways some of these industries impacted his own family–their jobs, livelihoods, and health. He also reflects on the changes he witnessed from the Iowa of his childhood–with more family farms, local businesses, and thriving small towns–to Iowa now with its massive industrial farms, gutted small towns, and poisoned environment.

The book is an exposé of unchecked power and an indictment of the extremely wealthy. But equally it is an indictment of government that promotes policies deregulating various food industries, while also empowering politicians who have much to gain from these industries. The already very wealthy industrialists and the politicians profit, while ordinary people suffer. Our food quality suffers. The workers picking our fruits and vegetables or packing our meat suffer. Our environment suffers. Our communities suffer.

Perhaps my favorite part of the book was how masterfully Frerick writes about the interconnectedness of our food systems with so many other aspects of our lives. By exploring and explaining the food system in the United States, Frerick’s book is also a story of economics, politics, immigration, labor, and more. Food is such a basic and foundational part of our lives; therefore, we can’t divorce the way our food system works from the impacts it has on our broader society and on us as individuals.

In demonstrating this interconnectedness, Frerick’s message is ultimately one of hope and solidarity–since we all have to eat, we are all impacted by our food system. We are all in this together, regardless of where we live, who we vote for, and what we believe. And the choices we make as a society about our food system–how and what we eat, how we treat the people who work in the food system, how we decide to regulate our food industries – have the power to reshape our lives and our communities for the better.

8 Responses

Thank you, Allison. The current crop of barons make the robber barons of the 1800’s look like small change. I am encouraged that despite the sleight of hand distractions from this truth, there are courageous voices speaking up clearly. Hopefully we are waking up.

Shocking! It would be difficult to describe the surprise I experienced this morning when I glanced at the topic of today’s blog. “farming”!! The name of the author revealed she could have grown up on the quarter across the section. As she laments in the article farming certainty has changed. On my way to the coop’s lunch room for coffee I will evaluate my growing corn. Grandpa’s yard stick for a prospective bumper crop was “knee high by the 4th”. I will be concern if my corn is not shoulder high . While drinking coffee at the coop I occasionally initiate conversation by sharing –Trump’s trade policies affecting the grain market, recent Synod’s decisions etc. but this morning; a blog in the Reformed Journal! Visser must have “Farm Journal” and” Reformed Journal” mixed up.

Thank you, Allison for stimulating my interest in reading “Barons”. I must check the community libraries and the two colleges between which I farm.

Excellent review. Definitely adding this to my TBR pile. Thank you.

Thanks Allison for this review. I look forward to reading the book. It fits well with two o5her books I have read the past couple months, both dealing with the impact of the hog industry and the water and air pollution from the farms.

The one is by Sonya Trom Eayrs: Dodge County, Incorporated: Big Ag and the Undoing of Rural America. Its focus is on the impact on Hormel Food and its contract farmers in Southeast Minnesota.

The other book is Wastelands: the True Story of Farm Country on Trial, by Corban Addison. It reads like a mystery trial and is focused on Smithfield and its contract farmers and the air pollution impact on the poor largely black neighbor population of the contract farmers.

They are both r3cent publications, 2024 and 2022 respectively.

You might also appreciate The Swine Republic:Struggles with the Truth about Agriculture and Water Quality by Christopher Jones, (2024). He was a research engineer at the University of Iowa but behind-the-scenes big ag had his university-based blog shut down and then he resigned from the school.

Steve,

Thanks for this tip. I assume the author also deals with the millions of dollars DesMoines has had to spend over the years to purify its drinking water it obtains from the rivers that are polluted by agricultural runoff. Another example of economic externalities that agriculture continues to push off on to the public.

$16,000 per day for the city of Des Moines to remove nitrates from agricultural runoff. DsM Waterworks has the biggest such equipment in the world. Still, we’re currently in a “no lawn watering” order. Not because of drought or low rivers, but because they simply can’t remove the nitrates fast enough.

Hmmm – beer barons and robber barons — maybe I should change my name lest I be counted among them? Thanks Allison and Frerick….😏