Last time, I posted an appreciative—and appreciated—reflection on Pope Francis. This time, I’m taking up quite a different figure. We’ll see about the appreciation.

Becoming the Wizard

In June 1944 a tornado ripped through the farm of Anthony Schuller near Alton, Iowa. Amid the utter devastation, 17-year-old Robert Harold Schuller, home for the summer after his freshman year at Hope College, might have called to mind The Wonderful Wizard of Oz. Its author, L. Frank Baum, summered near Holland, Michigan and Judy Garland had recently led her ragged troupe down the yellow brick road in the film version of the story. Oh, to have been swept away to the land of Oz, Robert might have mused, instead of being stranded in the ruins of “nowhere” Iowa.

Well, if you believe fervently enough and steel your will with dauntless determination, the story will come true. Such was the gospel Schuller picked up from Norman Vincent Peale during his, Schuller’s, first pastorate, in suburban Chicago. His land of Oz turned out to be Orange County, California, and there Schuller did not find but built his Emerald City. Its temple would be a Crystal Cathedral all glimmering with glass and splashing fountains, advertised to the world by a 250-foot Tower of Hope.

Schuller turned out not to be Dorothy with magic red slippers but Oz himself, with a relentless million-dollar smile.

Sins of Self-Doubt

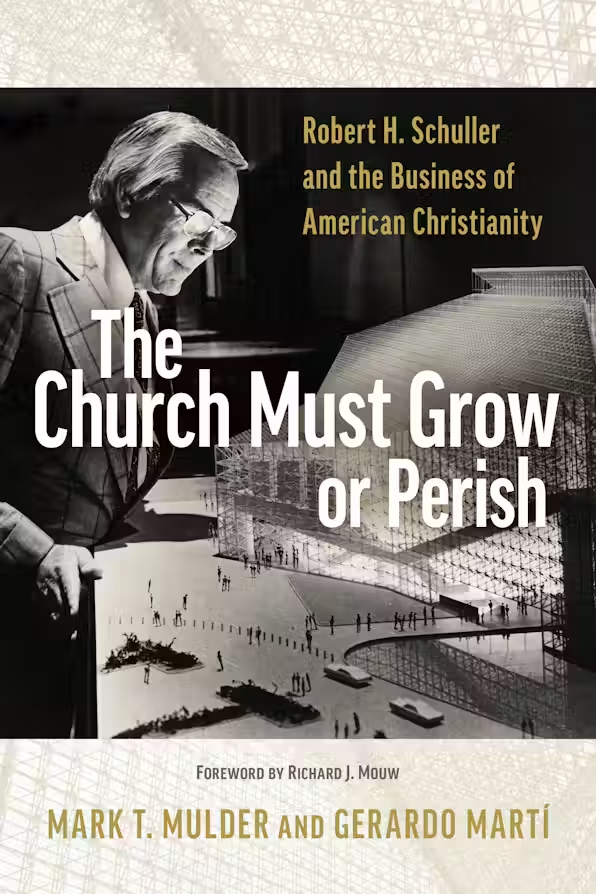

It was not always so. As sociologists Mark T. Mulder and Gerardo Marti show in their excellent new biography of the man, The Church Must Grow or Perish: Robert H. Schuller and the Business of American Christianity (Eerdmans, 2025), young Robert was something of a Cowardly Lion: pudgy, non-athletic, and undistinguished until he discovered his gift for theater in high school. He debuted by playing the female lead in drag. Courage indeed.

Yet the Cowardly Lion ever lurked. Schuller was a legendary builder and fundraiser, but professed to hate the latter as much as he loved the former. He was “periodically consumed by his own fear of failure,” say Mulder and Marti, and when his latest project teetered on insolvency, he might suffer panic attacks and even entertain a death wish (195). For all his Peale-ite nostrums, he “wrestled with an inability to master his own doubts” (200). Then too, while he avoided his rival televangelists’ public falls into lust (Swaggert, Bakker), Schuller struggled forever with gluttony (210-12).

Inventing the Megachurch

But private this all remained. His public face was ever shining, his building projects as successful as they were spectacular, his television ministry the largest, his celebrity guests A-list wannabes. Schuller went one step beyond Peale’s “positive thinking” to build his own brand of “possibility thinking.” Indeed, he announced the coming of a “new Reformation” that would dispatch the gloomy depths of sin and guilt of the original for the sunny uplands of self-esteem.

Yet fear drove this project too. Only such a Reformation could save the church from obsolescence, Schuller warned. Modern society was becoming ever more secular, and churches needed to “become more secular to defeat secularism.” (215) Away with the trappings of traditional religion (except for his preacher’s robe); enter the techniques and findings of market research to determine what people’s “needs” were and address them directly. The needs were inward, so the message was therapy with a minimum of theology and even less Bible exposition.

The Perfect Time and Place

We are so familiar with this now-outworn model of seeker-sensitive megachurches that it’s easy to forget that Schuller forged the template and could boast of remarkable success. Certainly, his location was perfect. Orange County from Schuller’s arrival in 1955 to the completion of the Crystal Cathedral in 1980 was the epitome of white suburban sprawl, with ever more people, freeways, big malls and strip malls and the great theme park of Disneyland. The whole was built around the automobile and television; hence the ample free parking at every stage of Schuller’s building expansion and the rise of his Hour of Power to international reach, and his chief revenue stream.

The times fit too. The 1950s saw religious affiliation hit its all-time peak in U.S. history, along with its public reputation and deference. The entire population was low-hanging fruit for the religious entrepreneur. Yet as Will Herberg demonstrated in his sociological classic of 1955, Protestant, Catholic, Jew, this piety was appallingly ignorant of Bible and the most basic theology. Secularism indeed! Schuller’s strategy was not to resist but accommodate the condition, to win people for “church” with something of a covert Christianity.

Retooled “Religion”

Schuller saw his audience as “intelligent, educated unbelievers” (206); Marti and Mulder demur. Intellectual doubts about the faith would not likely be relieved by therapeutic taglines. Rather, Schuller spoke to white middlebrow migrants from the heartland who were scrambling for success in the strange new world of perpetual sunshine, haunted by its shadows of rapid change and rootlessness, its demands of family building and commercial competition. To such, the sanctification of the market, the bolstering of ambition, and the model of St. Horatio Alger gave encouragement when strength lagged and self-doubt arose.

Thus, original sin turned out to be lack of self-esteem, with pride its cure, not Augustine’s curse. There was no social ethic here beyond the Protestant ethic. No encounter with race and racism at the peak of the civil rights movement. No reconsideration of patriotism during the Vietnam War. No doubts about consumerism. This was a self-centered religion with few restraints against self-centeredness but family obligations and business honesty.

We’ll see how it all came tumbling down in a minute. But first a note of lament about a lost opportunity. What if Schuller had not whistled past his own anxieties but put them out on the table and wrestled with them in front of people who doubtless had their own? What if he had tied them explicitly to biblical testimony and a theology of human frailty? It might have produced true healing for himself and deeper faith for his listeners.

The Crash

It also might have retained young people, who have proven to be just as immune to glib assurances as to fire and brimstone. Instead, as Christian Smith details in his new book, beginning in 1991 the rising generation started leaving the church in droves. Smith’s title is Schuller’s nightmare: Why Religion Went Obsolete: The Demise of Traditional Faith in America (Oxford University Press, 2025).

The year is particularly significant for in 1991 Schuller suffered a serious brain injury in Amsterdam and with it, per family and staff members, a creeping loss of command. He was 65 years old and might have left the stage. Fatefully, he held on until 2010 the same year his entire enterprise filed for bankruptcy.

What went wrong? First, he indulged his edifice complex one time too many. A new $47 million “Welcoming Center” was (as always with Schuller projects) heavily leveraged, and pledges fell $25 million short when the dot.com bubble burst in 2002. A new “Glory of Creation” pageant to match the proven winners of Christmas and Easter failed in 2005, with a $5 million loss. Donations to the Hour of Power, which had long carried the church budget, fell 24% in the wake of the stock market crash of 2007-09. Bankruptcy found the enterprise $48 million in debt.

Nepotism

Why this fateful compulsion to build? Because, Schuller insisted, only grand enterprises could galvanize new membership and higher levels of giving. To grow you had to keep growing. That paradox was matched by another. Schuller insisted that ministry be fresh, adaptive, and nimble, but his was ensconced in a huge, costly, fixed physical plant.

And administered by a huge bureaucracy too. Embarrassing enough for a critic of traditional denominations, but much worse in that his bureaucracy was liberally seeded with family members. His four adult children and their partners all had prominent staff positions with perks to match—at the end, twenty family members were pulling down nearly $2 million in total compensation (261).

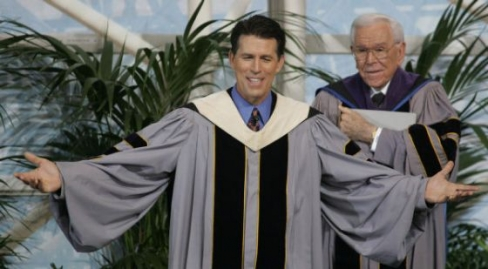

The succession scenario didn’t need the TV show to make it predictable; televangelists Oral Roberts had shown the way and Jerry Falwell would follow. Son Robert A. Schuller inherited his father’s mantle only to alienate the rest of the family by purging them, with all their conflicts of interest, from the board. Daughter Sheila Schuller Coleman took over and mounted an abysmal failure of a capital campaign to salvage the operation. And so was fulfilled the old joke: people who preach in glass churches should not stow thrones.

Peale’s Other Heir

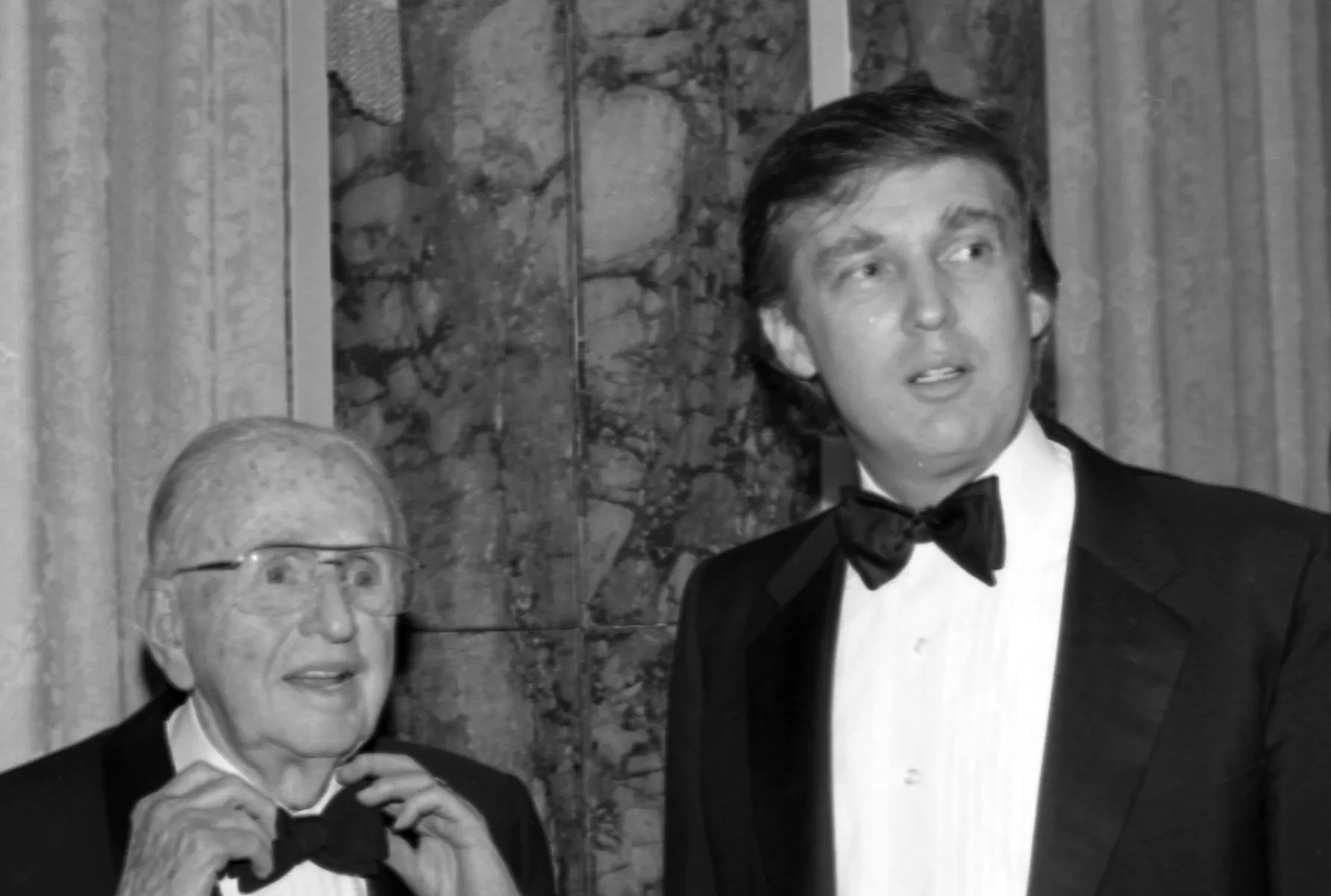

Chapman University and the Roman Catholic diocese of Orange got in a bidding war to take over the Cathedral, with the latter winning at $57.5 million. The grand old man died shrunken and destitute on April 2, 2015, at 88 years of age. Just two months later Donald Trump descended his golden escalator in Manhattan to announce his candidacy for president. This was the other true heir of Norman Vincent Peale, a pure pagan preaching the surly side of self-help that Peale usually, and Schuller always, kept hidden.

Perhaps more on him next time.

19 Responses

You almost made it. You avoided mentioning the Orange Man until the very end.

Said in jest: you almost made it through an RJ blog without feeling the need to make a snarky comment.

In this case, surely the mention of DJT is relevant, if not inevitable. Both Schuller and Trump were deeply influenced by Peale, and both had a profound influence on an important segment of American Christianity. How could one not point that out?

Hardly … the Orange Man is linked to Orange County, to all the feel-good preachments of East Coast Peale, West Coast Schuller, and the magachurch preachers with their pop psychology and entertainment skills. It’s all connected, and woe to those who fail to see the connections, for they become easy targets of superstition, political and religious. And those who see the connections are the prophets who “trouble Ahab!”

Yeah…..read Suburban Warriors….and really any one of more than 10 books by reputable authors who chronicle the Orange County…..apostolic reformation…..project 2025……heritage project…….the family……etc connections. Hillary wasn’t totally unhinged.

I, too, held my breath.

On a family trip to California when I was in high school, I wanted to go to church at the Crystal Cathedral. I walked up to the sanctuary doors with my infant brother in my arms, and was told by the usher (aka guard?) that we would have to sit somewhere else. We were directed to a far off corner, where it was clear that anyone who didn’t look like a well-off, white parishioner was sent to stay off the TV screen. It felt pretty disgusting.

I came for the “St. Horacio Alger” and stayed for the “edifice complex” and “people who preach in glass churches should not stow thrones!” Thanks for this hilarious and sobering review.

Schuller and Peale both can, I think, be fairly and even a bit charitably observed as unintentionally committing the error of most heretics. They asked important questions in the attempt to speak to “cultured despisers,” but in their attempts to speak in the language of the culture they lost the edge of the gospel. Peale tried to speak to businessmen and became a man of business. Schuller tried to speak to anxious strivers and in the end was consumed by his anxiety. We all have a choice as to whether to lean into the charity or the condemnation.

Interesting trivia: both Leo IV and Schuller have Dolton, Illinois roots. Different cathedrals.

You’ve made it crystal clear that a tower of crystal is far inferior to one of ivory.

Christianity, by and large, ever since Constantine, has confused two energies: the first is our task to love one another … and the other, is that of Christ, to build the church … Christ builds, we love.

In America, we’ve taken on the task of building the church with American energy and innovation … with five easy steps, and the latest technology, a “successful” church, counts nickels and noses to the gleeful tones of praise music and lovely images. In the process, loving one another, loving God, loving neighbor, grows confused, and lost.

As noted here, in the most tumultuous of times, Schuller and his school were unable to address the realities of the day, and share honestly their own struggles. It all became victory, and humility was told to take a hike.

I went to the Crystal Cathedral before it was built, I found Schuller’s care for “the lost” to be a good thing; I read Rick Warren, and attended Willow Creek many times. There was goodness there, but in the end, growth becomes growth at all costs … everything costs, and the investment in steel and concrete, glass and glamor, soon becomes the master.

This looks like a good book; an important contribution to understanding how in the world we got to the place of White Christian Nationalism bowing the knee to the Beast in the White House (excuse me, did I just write that?).

Thanks for this review. Amen and Amen!

Great article! Another thing Schuller and the president have in common: an obsession with building towers. I have this book next to me that indicates a belief in the cosmic capabilities of large buildings is an old and not entirely unproblematic one. We should probably think about that more. I recall when a church I attended was embarking on a building expansion program and the finances were looking downright scary, folk responded, “But this will put us on the map!” assuring us the new building would attract new members who would then pay for it. Schuller’s career is a bright warning sign flashing red over that way of thinking. Jesus, after all, wasn’t a home-owner.

Thank you for writing this!

In my earlier life as a religion writer, I met and interviewed Robert Schuller many times. I would describe him as by far the most insecure person of renown I ever encountered.

Back in the day the Wittenburg Door had a one page article asking what one could do with 15 million dollars. The answer was an amazing list of social justice fixes OR build one glass church. Perhaps that skewed sense of values is what reminds you of today’s politics. Perhaps even the One Big Beautiful Bill?

In the summer of 2006 I was asked to preach in the Cathedral. It was the height of the Lebanon War and Sally and I were living in East Jerusalem. I was not honored. I was petrified. But I said yes, because how could you say no to that. Well you could I suppose. None of the Schullers were there. I preached a message based on the Canaanite women with the ailing child. I pushed the edges as much as I dared. Some people got up and walked out. But at the end I got a standing ovation. Not sure if that meant I did a good job or didn’t do my job at all. I also had someone try to get to me between services — so maybe I did okay after all. I had a “bodyguard” throughout the morning. So did Sally who was sitting in the audience. Afterwards, an older man said to me “You are a dangerous man.” He probably did not consider that a compliment, but I kind of do — now anyway. That Sunday service did not make the cut for the Hour of Power. I expect it was too controversial. On the way to the airport the next morning, Schuller called and thanked me for coming. That was before he watched the video, I’m guessing. I don’t know why I’m telling you all this, except ego, but I also want to say that it was terrifying up to the point where I started to preach. Then everything slowed down for me. Whatever that was, and whatever role the place played in it, I’ll never forget it. Or him.

In 1983 I was called by the Synod of Michigan (now Synod of the Great Lakes) to start a church in the rapidly growing suburbs of northwest Columbus, Ohio. I had several who counseled me to wait, suggesting that I had the capability of pastoring a “good church.” I wrote to Bob Schuller, mentioning that I was considering this call. Bob kindly responded and said, “I believe that the greatest churches in America have yet to be started.” I accepted the call, moved to Dublin, OH in 1984 and retired from there in 2022.

As a New Church Development pastor (I still resist the term church planter), I can say that Bob Schuller unequivocally left his spiritual imprint on me and the church of which I am founding pastor. We corresponded and met in person over the years and he was always the encourager. Did Bob have his flaws? Certainly, as do we all. Still, I would not be who I am/was in ministry and the church of which I am founding pastor would not be who it is today, without the encouragement and guidance of Bob and Arvella Schuller. I will be forever grateful for and indebted to them both.

Jim, this article is excellent and I’m glad you did it. In my forthcoming The Soulwork of Justice, I share some thoughts about Bob Schuller in the chapter “From Grandiosity to Authenticity.” I knew him fairly well as he asked me to serve on his Board. Here’s what’s in my book. More stories could be shared, but best over coffee rather than in print,

“Taking a close look at admired and successful public figures you can sometimes spot the malignant growth of grandiosity. In my work as the general secretary of the Reformed Church in America, I had gotten to know the late Bob Schuller, known for leading the highly popular Hour of Power TV broadcast and building the Crystal Cathedral. Part of our denomination, Dr. Schuler’s influence was enormous, and global. Countless times in ecumenical travel around the world I’d hear from people thankful for the ways the Hour of Power had blessed and encouraged them in ministry.

When I first went to visit Bob in his California office, he showed me the framed baptismal gown hanging on the wall which he had worn as an infant when baptized at a small RCA church in Iowa. He has called that gown his most prized possession. But as he showed me the gown, tears welled up in his eyes. He admitted had never felt fully affirmed and accepted by his denominational family, and was wounded by that deficit, despite his world-wide fame and success. Something he clearly craved. I wondered why such a gifted person, who had achieved such enormous success, could still seek approval.

Over time it seemed to me that in his powerful, inspiring sermons about possibility thinking, he was often preaching to himself.

Dr. Schuller’s stellar career ended tragically. Like many highly effective leaders whose inward, unexamined fragile egos are protected by grandiosity, giving up power can feel mortally threatening. This is often seen with founding pastors of new congregations, inspiring leaders of social movements, countless politicians (including some recent Presidents), activists who have successfully built vital organizations, mega-church pastors who have spawned multiplying worship centers, and many others. What I saw in Bob, I also saw in myself. Perhaps that’s why I was so attuned to it. Maybe you can see this in yourself, too.

In Bob Schuller’s case, he was never able to transfer power, even to his own son. In a complex story of familial and organizational dysfunction, a 50-million-dollar ministry went bankrupt, and the Crystal Cathedral was sold to the Catholic Archdiocese of Orange to pay debts.

Success and achievement don’t diminish grandiosity. They inflate it. Our movement toward authenticity has to begin inwardly, away from the crowds. It requires detachment from the fruit of your actions. And that’s one definition of prayer.”