One way or another, probably all of us are pondering the possibility of hope these days. Some days we “feel” hope, some days we “do” hope, and some days hope is elusive. We try not to calibrate our hope to the daily pummeling of “wins” and “losses”—but it’s hard not to. And we wonder what kind of hope our faith affords in this tough moment.

Fortunately—if you care about this sort of thing—the sociological literature on hope is a growing field. Can a bunch of sociologists offer us some insight on hope? I was recently part of a lively conversation in which we tried to figure that out.

I serve on the Research Advisory Team for the BTS Center, a group of incredible people whose mission is to “catalyze spiritual imagination with enduring wisdom for transformative faith leadership.” In particular, they help faith leaders and faith communities explore how to respond to the crises of our time, especially climate change. Studying the research—and doing research—are part of their mission, too, which is why the Research Advisory Team got together a few months ago to explore the research on hope.

We read a series of articles, all of which offered helpful insights. We talked about “constructive hope” and “false hope,” “constructive doubt” and “fatalistic doubt.” We talked about “pathway thinking” and “agency thinking.” But we ended up focusing especially on a 2015 working paper by one of our members, Dr. Susanne Moser, and her collaborator, Dr. Carol L. Berzonsky.

We found especially helpful how this article presents a kind of taxonomy of hope (some of it based on the previous work of P. E. Stokes). As we discussed each variety of hope, we observed that people of faith have their own theological language to express each type. We might find each kind of hope, for example, within the Christian tradition, in our theological ideas and scriptural witness. What do we do with these varieties of hope? Let’s explore.

Pollyanna hope

This kind of hope says, “Everything’s gonna be fine! I don’t have to do anything about [this problem]!” The Christian version of this might be a simplistic but sincere declaration of Providence: God is in control! God is sovereign!

In Pollyanna hope, however, beneath those assurances about Providence can lurk two distortions: 1) denial or ignorance of difficult realities and 2) one’s own privilege: “I’m fine, so I don’t have to worry about it.” Or: “God will make sure everything is fine for me.” Another variation might be one of my late mother’s favorite phrases: “They’ll think of something.” Maybe God will “fix it,” whatever “it” is, but through other people, not me.

If we had to find a biblical expression of this one, I might choose good ol’ Jeremiah 29:11, “I know the plans I have for you, declares the Lord, plans to prosper you and not to harm you, plans to give you hope and a future.” More precisely, I might choose a common out-of-context citation of that verse. (By the way, if you want to hear a great sermon on this verse and how it’s used, check out Dr. Betsy King-MacDonald here.)

Active or heroic hope

Active hope says, “It’s gonna be fine, but I’m going to have to fight to make it happen.” We see this kind of hope commonly expressed in more optimistic activist spaces. This hope has confidence in a good outcome, eventually, but understands that good outcomes require human work. Let’s do it!

In a more theological mode, we might recognize a social justice inflection of faith here. “The moral arc of the universe is long, but it bends toward justice,” for example. With this kind of hope, we understand that God uses people to bring about redemptive purposes. So we work with God, confident that good will win out over evil.

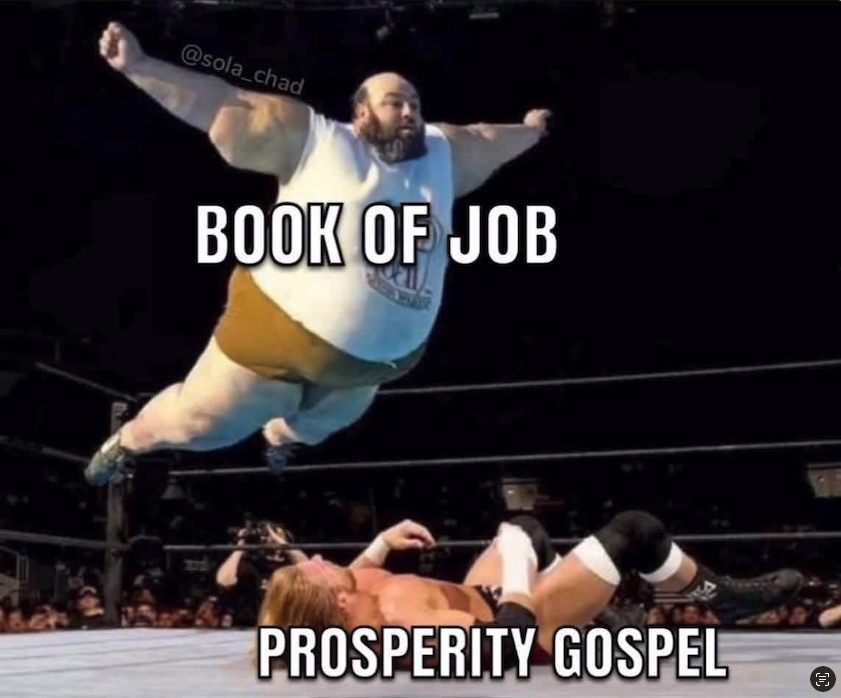

This one can detour into works righteousness or even prosperity gospel mode. If I’m “good,” then God will bless my goodness with success for my cause or even with prosperity for me. Name it and claim it. And if things aren’t going well, perhaps we need to adjust our technique or programs or behavior? If we can just get it right, God will bless our cause.

We can find this outlook supported throughout scripture, too. Psalm 1, for example, in which the righteous one is blessed and the wicked one blows away like chaff. Or Psalm 121, in which the Lord “will not let your foot slip.” As long as you are on the right side, what you do will “work.”

Stoic hope

“I’m not sure about the outcome, but I’ll take whatever comes. I’ll ride the wave and be OK.” Transposing this form of hope to a Christian mode, we might describe this as a more resigned view of Providence. We acknowledge that God is in control, but we do not assume God will make everything okey-dokey for us or others. We might also add an addendum, “God won’t give me more than I can bear.” (By the way, as you probably know, this idea is not found in the Bible—1 Cor. 10:13 is about temptation, not suffering.)

I might suggest that Romans 8, especially verse 28, expresses this view: “in all things, God works for the good of those who love him.” We acknowledge that our life in God includes suffering, but somehow we will be OK. God will turn that suffering to good.

Grounded hope

Here, “a person is realistically informed about the state of affairs, and thus skeptical of a positive outlook, but chooses to do whatever she or he can to bring about the best possible outcome, because standing by is an unacceptable and unethical option” (Moser/Berzonsky, p. 9).

This version strikes me as the way most activists actually organize their hope, even if their public persona sounds more like the Heroic version. In Grounded hope, the outcome is not at all certain, but our task is clear: we work for the cause or outcome because it’s the right thing to do. Philosophers would describe this as virtue ethics.

Joanna Macy, the Buddhist philosopher and activist who died this past month, was a famous proponent of Grounded hope, especially in her 2012 book with Chris Johnstone, Active Hope: How to Face the Mess We’re in without Going Crazy. I see this version expressed among many Black activists, too, including Austin Channing Brown and Ta-nehesi Coates, who write about the inevitability of “the struggle.” Grounded hope does not have to be grim: the great Ayana Elizabeth Johnson, author of What If We Get It Right?: Visions of Climate Futures, seems cheerful and optimistic, but she knows the score.

In a Christian mode, this form of hope might sound like, “Well, God calls us to be faithful, not successful.” We might acknowledge the power and pervasiveness of sin and injustice. We might look to scriptural passages like the ones in which Jesus instructs us to “take up your cross and follow me” (Matthew 16:24).

This form of hope recognizes that full redemption, the renewal of all things, complete shalom in the garden city—all that is our ultimate hope, not necessarily our proximate hope. “In this world you will have trouble,” says Jesus (John 16:33). That’s the reality we experience. The “I have overcome the world” part seems to glimmer on a distant horizon.

I wonder if this is the kind of hope Job feels amid his terrible suffering, when he nevertheless declares: “Though he slay me, yet will I trust him” (Job 13:15).

Radical hope

In this form of hope, a good outcome is not guaranteed, nor are the means to get there clear. Dr. Moser offers her own image for this kind of hope: a crew of rowers. They’re working together, pulling hard, but sitting backwards in the shell, moving toward a goal they can imagine but cannot see.

This version, I think, dwells more in the mystery of God. God does not always reveal everything we want to know, least of all the specifics of the future. “My thoughts are not your thoughts,” says the Lord (Isaiah 55:8). Our efforts, however well intentioned, do not always succeed. The people of God often suffer, sometimes for no apparent reason. This one is about humility before God and trust in guidance for today even if things look grim. Even though we can’t see our way through, we do the next right thing as best we can.

Hebrews 11:1 helps us here: “Faith is the assurance of things hoped for, the conviction of things not seen.” I wonder if Ecclesiastes might be the signal book for radical hope, with its deep sense of our human limitations and the mystery of God, along with the wisdom both of work and pleasure in life.

What to make of all this?

I don’t want to draw a simple line from “immature” Pollyanna hope to “mature” Radical hope. I find in my own inner turmoil, I shift around that spectrum (if it is a spectrum) all the time, and maybe that’s OK. I would, however, want to resist the passivity of both Pollyanna and Stoic hope, for reasons along the lines of “faith without works is dead” (James 2, also Matthew 25). Passivity, moreover, can often amount to complicity in systems that benefit ourselves though they may be harmful or disastrous for others. Passivity, in other words, can be a failure to love one’s neighbor (and/or the earth, I would add).

In terms of motivating people to act constructively in response to climate change, our group talked about the need for “reorientation” to the factual realities of climate change: causes, impacts, and mitigation/adaptation strategies. That reorientation can bring people into a period of despair, where their old versions of hope fall apart. The same could be said about any grievous reality, such as racial injustice. Getting through that painful reorientation stage requires inner work. Moser/Berzonsky write that the inner work “begins with having the courage—counter-intuitively—to go to hopelessness, to our own despair” (p. 9).

Fortunately, in the Christian tradition, we (should) know how to do that. We have the Psalms and so many other scriptures in which the people of God cry out in anguish; we have Jesus, the man of sorrows; and we have each other. Most of all, we have confidence in the goodness and faithfulness of God, in God’s long arc of redemption for “all things,” as Colossians 1 reminds us. But as our group observed, here and now we need active formation into mature hope. We can’t just get there willy-nilly. We need reflection, practice, allies. Ideally, our faith traditions offer resources to help immensely with all this.

Dr. Moser attempted to summarize mature hope as a combination of elements. Her presentation during our meeting concluding with this definition: “Standing on an ever-changing foundation of uncertainty and change, hope arises from the tension between a deep understanding of history and a bold vision of a largely unwritten future. It is a motivation experienced in the present, combined with an ability to see far, and a commitment to contribute constructively to building that future.”

Mature hope, in other words, requires a steely-eyed reality check about the present, a vision for the future, action in the present toward that future—and friends to work alongside us and keep us propped up when we feel weak.

My own version of this attempt at mature hope leans hard on Reformed theology. We profess a vision of an eschatological future in which God redeems all things through Christ. We insist on a humble assessment of our human efficacy—we do not save the world. And for better or worse—better, in this case—we nevertheless urge each other with Reformed determination to work hard right now in the vineyards of the Lord, as witnesses to what God is doing in this world—through us, despite us, completely apart from us.

As Dr. Moser suggests, we are building a cathedral whose towers we may never see in this life. We are not the Architect. But we follow the plan with our particular skills for this stone on that stone, right here, right now.

*******

The article I cite here is Moser, S. C., and C. Berzonsky (2015). Hope in the Face of Climate Change: A Bridge Without Railing ─ A Working Paper. Quoted with permission. Paper is available here.

Further work by Susanne Moser is available here. Thanks to Dr. Moser for her wisdom and for permission to quote.

9 Responses

Thanks for this gift, Deb: a thorough and thoughtful discussion of hope, and so necessary. Your closing image of the cathedral reminded me of Wendell Berry’s imperative, “Plant sequoias.”

Did you talk about nuclear energy?

That would solve the problem.

That is, if you believe there is a problem.

That is, if you want the problem, such as it is, to be solved.

Wow, you harvested the fruit of an indepth consultation for us and we didn’t even have to endure airports and a hotel. This is such a timely reflection. Your elaboration of “mature hope” in the last three paragraphs is pure gold. Thank you!

Amen to that!

Thanks for an instructive overview! I still prize the word “providence” as a dear vessel containing pretty much what you outline as “radical hope,” but, granted, perhaps you have to be a cradle Calvinist to cling with such visceral love to an old-fashioned theological term. 😊 Can we get a link to the sermon you mentioned by Dr. Betsey King-Macdonald?

Thanks, Cathy. Yes, the link is there now. I forgot to put it in when I posted last night!

I can imagine this as a framework for a sermon on Christian hope, ending with your reflections on “mature hope.” Not sure how to keep it at a length most people would accept, but I was deeply blessed and encouraged by the reading of your article. Thank you!

Thank you, Deb, for sharing this important discussion you were blessed to participate in.

It reminded me of the Benedictine principle; hope is expressed in our prayers – ora – yes.

And God’s response is not “leave it to me” but “get to work.”

Ora – et – labora.

The communities of faith and democracy have much work to do.

Thanks for these ways of thinking about hope. As you note, it would seem that hope can be found along various spectra (passive—active, joyful—lamenting, patient—impatient, realistic—unrealistic), each of which is in constant flux depending on our faith, temperament and situation at the moment. What can help keep hope more stable is one more distinction: the one between subjective hope (our thoughts and feelings about the future) and objective hope (the object or person in which we place our hope). Psalm 71 refers to them both: the subjective “But as for me, I will always have hope” (verse 19) and the objective “For you have been my hope, O Sovereign Lord, my confidence since my youth” (verse 5). Ultimately, Jesus is our hope (Colossians 1:27), and that hope stands no matter how much our subjective hope fluctuates about climate change or anything else.