On the church calendar it’s the Feast of Saint James. My church, St. James Episcopal, is over 160 years old. We’ve celebrated another anniversary. The benediction pronounced, we stream into Parish Hall.

Smells of vegetarian stew and focaccia bread waft in the air. School kids butt in line behind old men with walkers. Moms corral toddlers. A teenager swipes an appetizer of brownies. Two women share secrets and giggle. We fill our plates—hummus and veggies, Norm and Sarah’s 5-cheese macaroni. Gotta love a church potluck!

We find a table and crowd around. Jenna and I, both divorced and remarried. A husband and wife fortunate to be in love for 35 years. A lesbian pair raising two kids. A happily married woman at church on her own. Conversation turns to how we met our partners. At a college dance. On e-Harmony. During church summer camp. There’s laughter. There’s affirmation. There are tears.

What there isn’t . . . is judgment. Instead, we’re all accepted. As equal people with a common human need, who found sustaining love. People who are safe and valued as we are. Like St. James’ open communion rail, everyone is welcome at the potluck table too.

Jesus proclaimed inclusive community by word and deed. Through banquet parables where everyone’s welcome (Luke 14:15-24). The poor. The marginalized. The disabled. Through table fellowship where everyone’s welcome (Matthew 9:10). Lepers. Prostitutes. Tax collectors. Outcasts. It’s that dream that still draws me, despite disillusionment with institutional Christianity, to Jesus. To, among other things, his vision of inclusive community.

While often controversial, philosopher Peter Singer is spot on in describing “the expanding circle.” He paints with a broad and optimistic brush, arguing that over the course of history, Western societies have widened the circle of people whose needs and interests count equally. Modern democracies don’t consist of family and tribe, but encompass—in theory at least—all human persons. All identities.

In my college classes students often ask why a Canadian like me chose to become an American. So I tell them. What still attracts me, 40 years later, is America’s dream. Not the economic dream of opportunity, but the moral dream of equality. At the start of our national experiment, Thomas Jefferson penned astonishingly inclusive words: “all men are created equal.”

Of course, he didn’t really mean all people. He meant white property-owning men. Certainly not women or slaves or indigenous pagans. But over the last century America has tried, by fits and starts, to live into the unqualified meaning of “all.” The suffragette feminists widened the circle to include women. The New Deal and Great Society include the poor. The Civil Rights Movement includes Blacks. The Americans with Disabilities Act includes people with disabilities. Marriage and gender equality laws include LGBTQIA+ minorities. America has been an expanding circle. With many flaws, many gaps, many exceptions—to be sure. But moving in the right direction.

Until now.

The moral calamity is that we’re backsliding from the dream of equality. Of inclusive community. The Trump administration desires—and is attempting to enact by force—a shrinking circle. One that excludes immigrants. Transpeople. BIPOC communities. Muslims. Women. The poor.

Republican leaders fancy a society that centers whites. Heterosexuals and cisgenders. Men. Christians. The wealthy. The Supreme Court is on board. So are many of our fellow citizens. The shrinking circle isn’t limited to Washington. Trump and company are aided and abetted by red state houses in Georgia and Louisiana, Texas and North Carolina and Iowa. It’s all abhorrent!

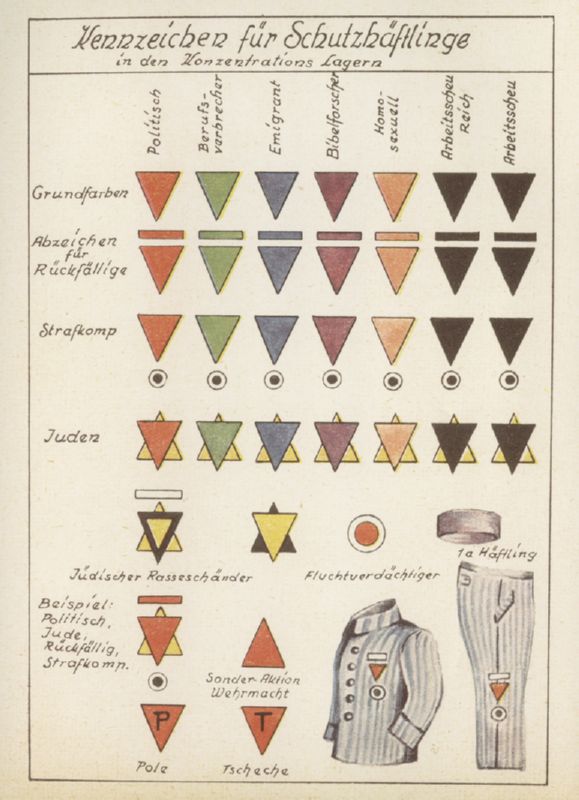

Historian Claudia Koonz offers insights that help explain this exclusionary shift. In contrast to Singer, she describes a contracting circle. It happened between 1933 and 1939. Instead of honoring universal human rights, “the Nazi conscience” separated people who deserved moral concern from those labeled less-than-fully human. Conscience, Koonz contends, isn’t private and it isn’t constant. It’s public and fluid. Removing Jews from the circle of moral obligation was carefully engineered.

In six years the outlook of ordinary Germans, who hadn’t been more prejudiced than citizens of other nations, extinguished neighborliness, respect, and compassion. Non-Aryans, sexual minorities, and the disabled were banished. Theologians helped advance this project. The anti-Semitic Gerhard Kittel, compiler of the authoritative Theological Dictionary of the New Testament, wanted Jews driven out of public life. While acknowledging the anguish this would bring, he calmed the conscience of Christians. Koonz’ analysis of the social mechanisms of ostracism is haunting.

The same shadow of exclusion is on display in America today. That’s why we who follow Jesus must defend the dream of equality. Of inclusion. We must do so at church. By setting a bigger table, not a smaller one. And, since faith isn’t confined to religious settings, we must do so at public gatherings as well.

The protest rally assembles at Federal Plaza in Chicago. Talk about plural representation—black lawmakers, white grandmas, powerchairs galore, pride flags too. I am one of the closing speakers. People are already pumped.

“Hey,” I call. “Y’all heard of the Pledge of Allegiance?” “Oh yeah,” the response comes back. “Well, it says that liberty and justice are for. . . ” “All!“—the raucous crowd shouts. “For whom?” “For all!” Repeat. Again.

I continue. “I’m sad to tell you that Republican lawmakers in Washington don’t believe the Pledge.” I hear boos. “They don’t believe in liberty and justice for all. They believe in liberty and justice for some.” More boos, louder now. “They’re pushing out folks they think don’t belong. Immigrants. Transpeople. Adults with disabilities like my son David.” The crowd hisses.

“But that’s not us. Is it?” Now I’m preaching! “Cause we believe in. . .” “Liberty and justice for all!” the crowd roars.

Indeed. Liberty and justice for all. For all. No exceptions.

A church dinner. A rally gathering. Jesus’ dream. Jefferson’s declaration. While not identical, they work in tandem. To envision an expanding circle. To enact a community where boundaries dissolve to make space for everyone. Everyone.

So . . . when’s the next potluck?

Header photo by Buddy AN on Unsplash

7 Responses

Amen! WE, the people.

“Of course, he [Jefferson] didn’t really mean all people. He meant white property-owning men. Certainly not women or slaves or indigenous pagans.”

I’m not certain that’s correct, and we should be especially wary of that “of course.” The conclusion would be that the American experiment was actually founded on not only a de facto inequality, but an embraced, approved, and desired inequality. It would mean, in fact, that Roger Taney was right, in his infamous Dred Scott decision.

This was actually at the heart of the argument between pro-slavery apologists, such as Stephen Douglas, and Abraham Lincoln, and featured prominently in the debates they held in Illinois in 1858.

It was the contention of Douglas and others that the Declaration’s assertion of equality was meant only to apply to elite white colonists in comparison with their peers in England, and that Blacks and slaves and women and etc. were no way in Jefferson’s purview. On that basis, they insisted that it was they, the pro-slavery party, that were the true Americans, holding to its original principles, and that the Republican Party–in their insistence on equality for all–were the innovators and deviationists.

Lincoln disagreed: “All honor to Jefferson–to the man who, in the concrete pressure of a struggle for national independence by a single people, had the coolness, forecast, and capacity to introduce into a merely revolutionary document, an abstract truth, applicable to all men and all times, and so to embalm it there, that to-day, and in all coming days, it shall be a rebuke and a stumbling-block to the very harbingers of re-appearing tyranny and oppression.”

John, I think your analysis is a useful contribution to this discussion. Two additional items for those interested in this conversation to consider: one is that Lincoln’s use of the DoI is seen by many historians as rhetorical cover for his deviationist position and constituted a sort of historical revisionism to serve the needs of the present moment in the 1850s. (Side note: I love how even in the 1850s the deification of the Founders meant that proto-originalism was seen as the preeminent measure of an interpretation.) Second is that even the word “equal” is fraught with contention since some meant political equality, some meant social equality, some meant spiritual equality, etc.–this includes Lincoln. For a really fascinating deep dive into the history of the phrase “all men are created equal,” see this fascinating law review article by historian Pauline Maier, whose book on the DoI is equally thought-provoking: https://scholarlycommons.law.wlu.edu/wlulr/vol56/iss3/8/ (see especially pages 885–7).

Yes, indeed, there are those–many of them–without not only don’t think Jefferson meant what he said, but who deny Lincoln meant what he said, also.

This is too complicated a discussion to have here. I would only remind folk who embrace that–can we call it cynical?–position that that places them on the side of Taney and the most radical of the pro-slavery secessionists of the 1850s and ’60s. (There was a debate on the pro-slavery side about this: Alexander Stephens –the vice president of the Confederacy–and many others took the position that Jefferson did mean what he said, but he was simply wrong.)

That uncomfortable fact–that one is aligning oneself with Dred Scott v Sandford, the most notorious decision ever delivered by a Supreme Court in the US, at least as far as the original conception of what the meaning of America was–doesn’t mean that the position is wrong. It might lead some to want to inquire more deeply into the matter, however.

As to the claim that Lincoln was guilty of “the deification of the Founders,” as you put it, here’s Lincoln’s take on that, from his Cooper Institute speech in 1860, where he goes to great lengths to discover what the founders said about slavery: “let me guard a little against being misunderstood. I do not mean to say we are bound to follow implicitly in whatever our fathers did. To do so, would be to discard all the lights of current experience – to reject all progress – all improvement.”

Another article about DEI. I feel sorry for the progressive Christians as this topic appears to be the majority of what will be preached about and discussed. We are so blessed in the United States where Justice and Liberty are available, for the most part, in enough quantity for all people to have a decent and fulfilling life within our current situation. The problem, in my mind, is they don’t have the family, community and/or personal resources to find a way to thrive. Christians can help, not exclusively by “fighting for DEI” at rallies to call for more government intervention, but by working together to help individual families and people. At the end of our lives this is what we will be judged for. My next church potluck will include just ordinary people from my community, and I’m not concerned about DEI makeup of our group.

Your response saddens me. You’re missing the kingdom of God as both current and future reality. Encourage you to learn more about what it means to be a reformed Christian.

I like how you “out-patriotize” Republican lawmakers in your speech at the Federal Plaza, calling into question whether they really believe the Pledge of Allegiance. In general, I also like your contrast between those who are expanding the circle and those who are shrinking it, but I question whether speaking of the church as a place where no judgments are made is the right way to put it. I know you have to write within the confines of a short blog to make a point, but I’m guessing you do recognize that some judgments are needed. Your own article goes on to judge Republican leaders, Trump, the Supreme Court, various state governments, Nazis, and those who shrink the circle. Even in Jesus’ actions and parables, judgment happened at the table: In Matthew 22’s version of the Parable of the Wedding Banquet, the excuse-givers are killed, and even among the multitudes invited in their place, a man without the proper attire is cast out. Elsewhere Jesus eats with “sinners,” but rebukes the Pharisees who questioned him about that. At a dinner party with Pharisees in Luke 14, Jesus rebuked his hosts on multiple fronts. Even at the Last Supper, Jesus said that for one of the guests, it would be better if he had not been born. Even for those expanding the kingdom circle, exercising good judgment is needed.