Among dozens of executive orders issued by President Trump immediately after Inauguration Day was an abrupt suspension of all processing of refugees. Families fleeing from civil war who had followed all the rules and waited months for their scheduled hearings were turned back at the border. Civilian workers for US forces in Afghanistan, in hiding from the Taliban, holding both their admission papers from the US and their plane tickets, were told to stay home. Setting aside its obligations under international law and United Nations conventions it had approved, the United States slammed the door.

A few months later, however, a narrow door opened. White South African farmers, the president claimed, are victims of brutal racial violence and oppression. Their land is being seized, Trump claimed, and Black thugs murder them at will while the government looks away. After the Trump administration announced the opening of the gates to these hapless victims of state-sanctioned violence and state-initiated land theft (“white genocide,” in his words), the first 59 applicants for refugee status were quickly approved, flown to the US in a government-chartered plane in May, and warmly welcomed to the White House. Thousands more applications are in process, report State Department officials.

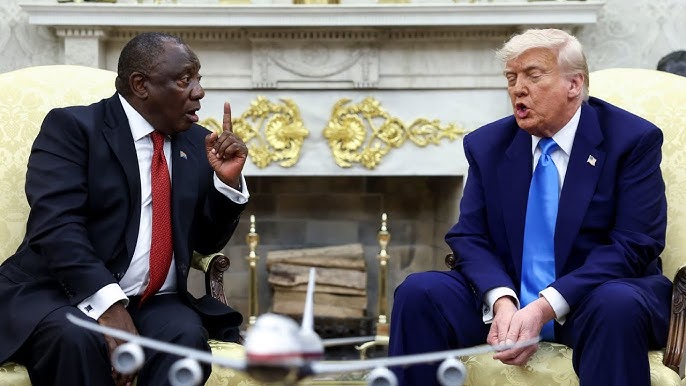

A week later, President Trump invited another South African to 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue: South Africa’s President Cyril Ramaphosa. What began as a conversation became a one-sided rant. The evidence of racial bias and violence against white farmers that Trump put forward—waving photos toward the news cameras, while his guest tried to see what they were—was mostly fake. “Look at all these white farmers’ bodies,” he said! The image was actually of civil war victims in Congo. Trump cued up a video of former African National Congress firebrand Julius Malema stirring up a crowd with a song whose lyrics condone violence against “the Boers.” That video is ten years old, and shortly after the rally seen in the video Malema was expelled from the ANC. “Look at the thousands of graves of white farmers in this photo of a funeral procession,” Trump said to his guest! News media tracked down this photo: it was taken at a 2020 funeral for one murdered farm couple, and the white crosses by the roadside were simply route markers, not graves.

In the real world (not the MAGA world) is anti-white violence really killing thousands? In 2024, Fareed Zakaria reported on CNN, 26,000 South Africans were murdered. Thirty-one of them were farmers. Most of the murdered farmers were white, no doubt: the seven percent white minority owns 72 percent of South Africa’s private farmland. The Black majority, about 80 percent of the population, owns just 4 percent. Is “white genocide” occurring in South Africa? Only in the fevered imagination of the American president and the right-wing pundits who shape his worldview.

A particular target of Republican rage—and a reason cited by the president in cancelling all humanitarian aid and other assistance to South Africa—is a 2024 expansion of eminent domain laws under which the government can claim private land for public purposes. Laws like this exist in almost every country. Owners receive compensation, but the new South African law allows compulsory seizure without compensation in some cases, subject to court review, if owners will not come to terms. No such transfers have been made, however.

My wife and I spent several months in South Africa in 2006, seeking to understand how the nation ended white minority rule and created a multiracial democracy without large-scale violence. During four years of constitutional debate from 1990 to 1994, white soldiers and paramilitary militias had faced off against the guerrilla fighters of the African National Congress, and civil war seemed imminent. Each time the representatives of the ANC and the Nationalist government came close to agreement, another roadblock, such as land reform, composition of the legislature, and criminal liability for past acts of violence on both sides, would bring negotiations to a halt. A peaceful end to 42 years of brutal racial division seemed forever out of reach.

What made it possible to come at last to agreement on a new constitution, widely recognized as one of the strongest in the world in its guarantees of civil rights, due process, and electoral accountability? A major factor was the extraordinary moral leadership of the ANC’s new leader, Nelson Mandela (1918-2013), who after 27 years’ imprisonment eschewed retribution in favor of reconciliation. Also essential was the readiness of National Party leaders to take their place as participants but not bosses of a new order—so long as their economic dominance was not threatened. And the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC), an innovative non-legal forum created to bring the horrors of the past to light and facilitate healing, played an important role. The TRC captured the attention of the country and the world, a bold venture in morality, politics, and, inescapably, religion. Its hearings, with their ritual solemnity, channeled the Christian faith of South Africans of all races into a spirit of forgiveness. (For more background see my article, “Truth, Reconciliation, and Human Rights: A Reflection on South Africa’s Transition to Multiracial Democracy”

And yet the dawn of multiracial democracy in 1994 did not bring a bright new day of fairness and equality. The nation has seen both remarkable progress and persistent stagnation. The poorest slums now have electricity (when it is working) and potable water. Black and mixed-race South Africans are no longer barred from shopping or working in white enclaves. But economic development has been slow and sporadic. Rates of murder, rape, armed robbery, and carjacking are among the highest in the world. South Africans of every ethnic identity plan carefully where and when they travel, and every supermarket and office car park posts armed guards. Corruption infects every level of government. What changed in the post-apartheid era, one commentator has observed, was only the color of the skin of those sitting in the back seat of government limousines, accepting bribes through the window.

South Africa is by no means a peaceful or healthy nation today, dashing the hopes of so many at the time of transition. And white South Africans do indeed face greater risks than in the days when Blacks who ventured into their neighborhoods, except gardeners and servants, were likely to be arrested. Nearly every white South African we met had been the victim of a car theft or a house break-in. So had many Blacks, Indian immigrants, and mixed-race South Africans.

Today every major South African corporation showcases its Black managers, but nearly all of them still report to white owners. International Monetary Fund figures show that income inequality, already high in 1990, is now much higher. The wealthiest 20 percent of South Africans now receive 70 percent of income, a gap 50 percent above the median in developing economies. Today there are far more wealthy Black South Africans than ever, to be sure. But youth unemployment is shockingly high—over 50 percent—and it affects the Black and mixed-race population far more than the white minority. In the first quarter of 2025, the unemployment rate for white South Africans was seven percent. For Blacks it was 34 percent.

Perhaps the rest of the world should not be overly concerned about a few dozen white South Africans who pretend to be fleeing a nonexistent race war. Most Afrikaners tell journalists they are bewildered as anyone by Trump’s claim that they must flee for their lives. They only want to live in their own country in peace, they say, recognizing the situation isn’t what it should be and that change takes time. On a recent trip to the Netherlands, we met a family of white South Africans now living in Europe. They said they left their homeland to seek better economic and educational opportunities abroad, not because they were victims of anti-white prejudice. They laughed out loud when we mentioned Trump’s allegations.

Let us not forget the sources of the violence that has ravaged South Africa for so long, both in the brutally repressive Nationalist regime from 1948 until 1990 and in the disruption and disorder of the years since. The system of strict racial segregation known as apartheid was created in 1948, drawing inspiration from the Jim Crow laws of the southern US. A deeper and more pervasive motivation was the conviction of the ruling party that Christian principles—specifically, the Calvinist tenets of the Dutch Reformed churches where Afrikaner elite worshiped—demand racial separation. Whites are destined for leadership and authority, blacks for manual labor. Whites and Blacks need to live in their own separate communities. From Reformed pulpits across the length and breadth of South Africa, white preachers assured their white congregations that their Black neighbors are happiest when they live in their own designated areas, receive the limited elementary-level education suited to their intellectual abilities, and work in factories, mines, and fields under the supervision of white owners and managers.

Having guided his nation through the tumultuous years of transition, Mandela became a hero to the entire globe. Another hero, far less renowned abroad but no less influential in bringing about the end of white rule, was the Reformed pastor Beyers Naudé (1915-2004). His pastor father was a founder of the Broederbond, a secret society of Afrikaner Calvinists that held wide influence in the Nationalist party, and his son was a member of that group in his early career. But after the Sharpeville massacre of 1960, Beyers came to the conviction that the apartheid system was both morally and theologically indefensible. For the rest of his life—continually under house arrest, prohibited from circulating his writing, barred from meeting with more than one person at a time—Naudé sought to persuade fellow Christians to repent of their tragic misreading of scripture.

Unlike in South Africa during the apartheid years, those who promote white nationalism in the US do not usually claim an explicitly Calvinist rationale for their denigration of immigrants and people of color. Instead they rely on fear and fantasy: migrants are criminals, asylum-seekers are fraudsters, diversity hires are incompetent, and so on. But they are drawing from the same well of racial discrimination and mistrust that sustained the apartheid government of South Africa for three decades. And they too claim that God has called them to stand up for white people in the face of relentless persecution by people of color and their allies.

Ideologies advocating white supremacy are seldom voiced in South Africa today, at least in public. And I believe we should let the few dozen white South African farmers enjoy their new life in America. They pose no danger to the rest of us. But the narrative of “white genocide” and black criminality—the president’s rationale for welcoming them while rejecting everyone else—is not only false but dangerously so. And the principle that is implicit if not explicit in recent executive actions—white people are good, Black and brown people are bad—is an egregious affront to our nation’s most cherished values.

Both the US and South Africa are multiracial democracies, and both face daunting challenges in overcoming past and present racial inequities and inequalities. Claiming a divine mandate to detain and deport nonwhite residents of the US whether or not they hold a green card, like appealing to Calvinist theology in support of apartheid, is worshiping a false god. The God of the scriptures demands that we love our neighbors and treat them justly—all of our neighbors, who are all made in God’s image—not just those whose skin is white.

9 Responses

Amen.

Thank you professor, for your reflections on South Africa, then and now.

I just finished reading Nelson Mandela’s autobiography “LONG WALK TO FREEDOM.”

What a journey he took. Those years after his release were torturous, with much bloodshed.

I found many parallels with how Palestinians are seeking a pluralistic government in Israel/Palestine.

Will there ever be “justice and liberty for all” in any country under the face of the sun?

What a long walk indeed.

Thank you for the concise history lesson and clear warning.

An excellent and insightful piece. Thank you, David.

Thank you for this. You identified and clarified so many important things. So necessary.

A few weeks ago on this site you people (😉) decried the racism that led people to leave Englewood, then Roseland, then South Holland. You’re all experts in “redlining” from the 1950’s (it sure didn’t work, did it?) but some of you have no clue about how the political power (including Obama) use housing laws and policies to move the undesirable poor black people out of valuable real estate areas of Chicago into suburbs, like South Holland.

Today, you decry the racing letting white South Africans in the US. Do you really think the power structure in South Africa doesn’t have antipathy (to put it mildly) toward these farmers? Do you remember Rhodesia? Perhaps some of you should move to Johannesburg. I’ll bet housing is cheaper there than even South Holland.

Suggestion for next week: Today Trump is attempting to stop violence in Washington DC. He won’t be prosecuting people like you. Will it be racist if he cleans up the city? Even if it makes life better for law-abiding people who live there?

Here’s my point: the battle over racism really isn’t between black people and white people. It’s between two groups of white peoples who disagree about everything else.

Marty

How about the powerful vs the powerless? We white dutch folks definitely hail from positions of privilege. Thanks Prof H for helping to inform our dialogue.

I appreciate your points, but I think you have overlooked some of the more recent history in South Africa. That one video may have been older, but the same guy who was booted from the ANC (Malema) then formed his own party and has held a seat in SA’s parliament for years. The New York Times was reporting on them as recently as 2023.

And, there is apparently an epidemic of violence against the farmers, if the Daily Mail is to be believed (which perhaps it often shouldn’t be): https://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-12576995/SUE-REID-Theres-murder-week-farms-South-Africa-year-race-baiting-Marxist-loves-singing-Kill-Boer-set-Vice-President.html. That might be a slanted article, but it seems to be pretty well rooted in fact. I for one am not quite as convinced that SA might not potentially have refugees due to racial violence, although I’m not sure what the standard is for that, and I’m sure Trump overstated the case.

Suffice to say there does seem to be a lot of very overt racial hatred and violence in South Africa of a type we do not see here in the United States. While there may be some overt racial hatred here, I cannot imagine any national level politician leading a rally to tens of thousands of people urging them to slaughter people because of their skin color (despite whatever underlying motivations we might want to ascribe to him). That this guy is in the SA national assembly and has been chanting to kill the white farmers with rapturous audiences cheering him on for DECADES is just wild. I’m just glad my ancestors landed here instead of South Africa!

Whether deporting people from the US is fair is one thing, but I don’t think it’s a very good analogue to South Africa. I suspect the deportation “looks” racially motivated because most people “eligible” to be deported happen to be non-white. They seem to be just going after anyone and everyone at this point, including a bunch of Irish and European visa overstays. Trying to focus on race risks distracting from a more interesting issue of what Scripture has to say about immigration and deportation, if anything…

David,

Thank you for this clear-eyed, factual, and balanced essay. I especially appreciated how you concluded: “The God of the scriptures demands that we love our neighbors and treat them justly—all of our neighbors, who are all made in God’s image—not just those whose skin is white.”

It’s that simple–which makes what’s happening today so sad, and so frustrating that so many Christians seem blind to the “racial inequalities and inequities” your essay makes clear.

I’m reminded of Mary Oliver’s prophetic poem, “Of the Empire,” where she writes about our culture: “We will be remembered as a culture that feared death and adored power, that tried to vanquish insecurity for the few and cared little for the penury of the many….the heart…in those days, was small, and hard, and full of meanness.”

Thanks for your conviction and your kindness here.