When I completed my Ph.D. in European and Russian history at the University of Maryland in June 1972, I was offered a position at the Department of State through my mentor’s connections with its leaders. While I thoroughly enjoyed my research and writing job, especially my work on U.S.- Soviet relations, I decided after four years to pursue a teaching job, which had been my career goal since high school. The decision to leave the Department of State was an easy one when the Christian College Coalition invited me to establish the American Studies Program.

After 20 years of work, which included the opportunity to develop off-campus programs in the States and overseas, the president of the newly renamed Council for Christian Colleges & Universities asked me to take charge of the Russian Initiative. This program was created in response to a request from member schools for the Council’s assistance in developing exchange programs with Soviet universities. I eagerly accepted this invitation and traveled to Moscow for the first time in October 1990. As I stood in Red Square looking at the Kremlin and St. Basil’s Cathedral, I remember thinking, “What is a guy from Chicago doing alone in Red Square—the heart of America’s Super Power rival?”

One year later, in 1991, another remarkable invitation came my way. I received a letter from Mikhail Morgulis, the director of Project Christian Bridge. Morgulis was a Russian émigré with extensive experience in the publishing industry and numerous ties to Russian authors and some Kremlin officials. His letter stated that Mikhail Gorbachev, Boris Yeltsin, and leaders of the Supreme Soviet, were inviting a delegation of “influential Christian leaders” to meet with high-level Soviet government leaders. Most of the 19-member American delegation were evangelical pastors and missionaries or heads of Christian nonprofit organizations active in the USRR. I found out later that I was included in the list of invitees because of my work with Christian colleges and universities, with whom the Soviet leaders wanted to develop student and faculty exchanges.

This was another shocking moment for this Chicago boy. I had never met either of the two Senators from Illinois, or the mayor of Chicago, or even the mayor of my hometown, Cicero, and now I was being invited to Moscow to meet Mikhail Gorbachev, Boris Yeltsin, and other Soviet leaders, the leaders of a country that had persecuted Christians for decades.

We were being invited into the middle of a complex battle for power in Moscow. Mikhail Gorbachev’s resignation as General Secretary of the Communist Party on August 24, 1991, following the collapse of an attempted coup, made a dramatic statement about the failure of the Marxist-Leninist system, but he continued as President of the Soviet Union. Boris Yeltsin, the hero of the resistance to the August coup, bolstered his position when he became the first popularly elected president of the Russian Republic, the largest and most powerful of the fifteen republics in the USSR. In the months following the attempted coup, Yeltsin and Gorbachev battled with each other over the control of the government in Moscow.

Our invitation included a letter from five members of the Supreme Soviet, led by Konstantin Lubenchenko, whose visit to the Washington earlier in the year prompted our invitation. The letter said: ‘In the difficult, often agonizing, transitional period that our country is experiencing in moving from that of a totalitarian system to parliamentarism, a market economy, and an open society, spiritual and moral values acquire a great, if not paramount, significance in their ability to guarantee us against confrontation, civil conflicts, the erosion of moral foundations, and the lowering of standards.

“We know the role which your Christian organizations are playing as you follow the great words of Christ: ‘Faith without works is dead.’ You are able to assist in the social development of a country, and you are able to establish friendly relations with other countries, including the Soviet Union.” Their letter concluded with asking for assistance and noting that the Russian people “are devoted to the moral values of Christianity.”

In response, our delegation sent a message to the members of the Supreme Soviet that read: “We are not coming to promote Americanism or capitalism, though we appreciate our country and are aware of the benefits free markets have provided.” The letter then summarized our purpose for coming to Moscow as: “First, to encourage understanding and facilitate cooperation between American Christians and the governments of the USSR, Russia, and Ukraine; second, to promote Christian ideas and values as a means of positively influencing family life, social problems, business ethics, education, democratic structures, humanitarian venues, and charitable activities; third, to support understanding and cooperation between Protestants, Orthodox and Catholics; and fourth, to promote religious freedom and equality of rights for all religious groups.”

As our delegation held discussions in advance of the trip, we urged each other to avoid any tone of triumphalism and to approach the Soviets with respect. We also decided to be honest about the weaknesses of our country and the American church in particular.

When we landed in Moscow, we were met by a Soviet television crew. It was a signal that our visit was going to be a high-profile event, which was a new experience for me. The coverage emphasized that this was the first visit of Christian leaders to Moscow at the invitation of the Soviet government and was highlighted prominently on Soviet television.

In my journal, I noted that Moscow was “one huge traffic jam” and that every store was jammed with long lines of people—something I had not seen on my three earlier trips. We were taken to the Oktyabrskaya Hotel, which was formerly owned and controlled by the Central Party of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union but had recently been taken over by President Gorbachev’s staff. With its marbled corridors, impressive atrium, Persian rugs, and spacious wood-paneled suites, it was the most beautiful hotel in the Soviet Union. This was the type of luxury Communist Party leaders enjoyed while the average Muscovite suffered in sub-standard public housing.

After our arrival, our schedule changed almost every day, and we had a growing sense that the power struggle between Gorbachev and Yeltsin was part of the problem. We had a feeling that we might not get a chance to see either of these presidents. Halfway through the week, it was clear that a meeting with Yeltsin was not possible, but we celebrated when we got the news that a meeting with Gorbachev had been confirmed and would take place in the Kremlin on Monday, November 4—right at the end of our visit.

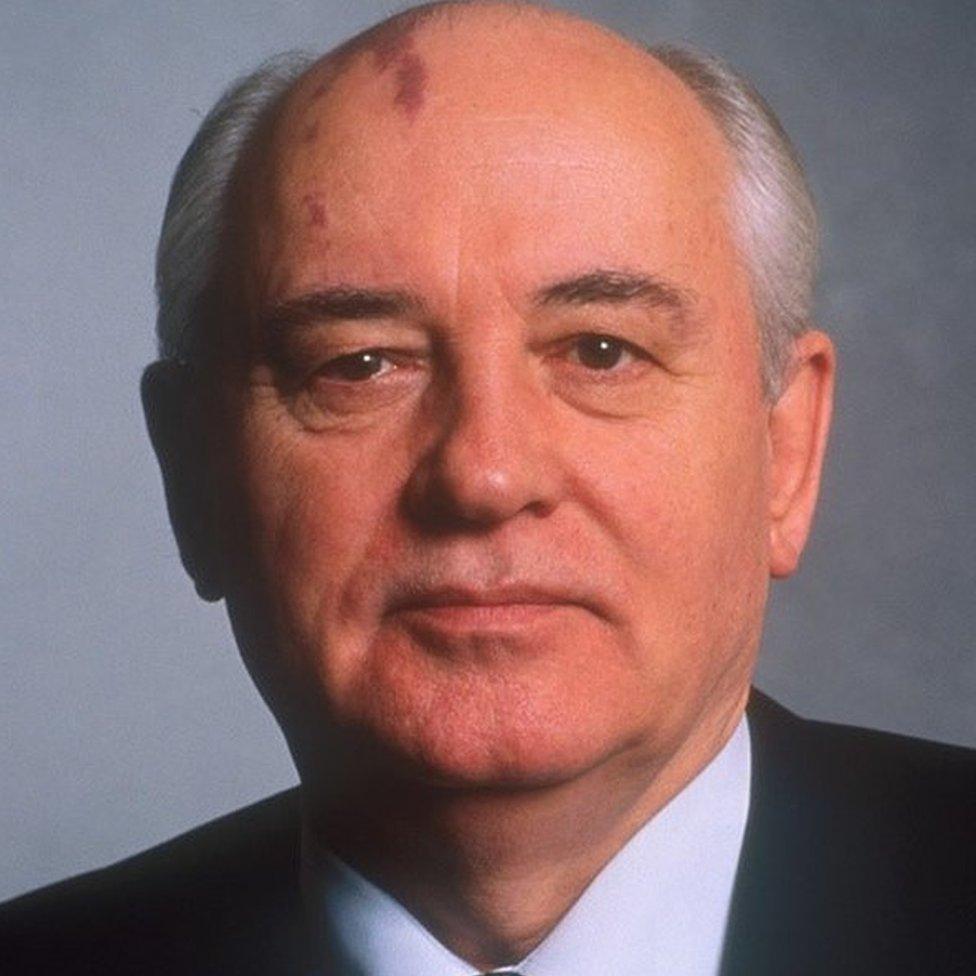

Philip Yancey, a member of our delegation, wrote a report on the meeting with Gorbachev that was superb. He graphically described our bus ride to the Kremlin, which was late as usual. When we entered the Kremlin through the red brick Spassky Gate, presidential assistants anxiously greeted us and encouraged us to quickly enter the presidential office complex located in an elegant hall built by the tsars. No metal detectors were used when arrived, and we were quickly escorted into a room where Gorbachev awaited us. He shook hands with each member of the delegation and directed us to our seats. Meanwhile, his staff of young men entered through a side door with plates of biscuits and cups of tea on state china. Gorbachev’s opening statement showed he had been well-briefed, and as he spoke, we felt his focus and desire to communicate with us directly.

“I have read your letter, and I thank you for it,” he began. “I found it very warm and moving.” He then openly shared that his country was going through a difficult time and said, “We are in a crisis, including a spiritual crisis . . . Civil strife and division are springing up everywhere. In the past, change in my country has come with a circle of blood; now we are trying to bring about change democratically.”

Gorbachev seemed vigorous, healthy, and fully in command of the meeting. In his opening remarks he said, “Let me be honest with you. I am an atheist. I believe that man is at the center and must solve his own problems. That is my faith. Even so, I have profound respect for your beliefs. This time, more than ever before, we need support from our partners, and I value solidarity with religion.” Later in the discussion, Gorbachev summarized his position with these words: “I must say that for a long time I have drawn comfort from the Bible. Ignoring religious experience has meant great losses for society. And I must acknowledge that Christians are doing much better than our political leaders on important questions facing us. We welcome your help, especially when it is accompanied by deeds. My favorite line in your letter is, ‘Faith without deeds is dead.’”

Both our delegation and Gorbachev and his associates obviously enjoyed the meeting. He took the time to shake each of our hands again at its conclusion. He also bowed his head and shut his eyes when Mikhail Morgulis offered a closing prayer. His departing words were: “It has been a long time since I met a delegation that came offering to help and not to criticize.”

Mikhail Gorbachev and Vladimir Putin: The “What Ifs” of History

After this trip, and during the 20 years of working with the Russian-American Christian University that followed, I often wondered what would have happened to Russia if Gorbachev had survived Yeltsin’s attacks and the decision to appoint as Yeltsin’s successor the unknown minor KGB officer, Vladimir Putin, had never happened. What would the world look like today if Putin and his cohort of KGB officials from St. Petersburg—who were preparing to take advantage of Russia’s chaos in the 1990s and seizing a large share of the country’s assets—had never been given the highest access to power?

Gorbachev Putin

Bring an end to the Cold War Replace the US as the global leader

Limit nuclear weaponry Become the dominant nuclear power

Democratic reform (Perestroika) Repressive domestic political life

Freedom of the press (Glasnost) Government controlled media

Freedom of religion Mono-religion – state-controlled church

Friendship with American presidents Hostility toward American’s world status

A personal footnote: I had the privilege of attending all the meetings during the days before the final session with Gorbachev. I knew when the trip began that if the meeting with Gorbachev was changed and moved to the end of our schedule, I would have to depart early for the wedding of my son Mark back in Washington, D.C., on Sunday, November 3. As it happened, I was able to be at both milestone events – and Mark was forgiven for his scheduling!

5 Responses

Thank you for that interesting outline when Russia welcomed Christian leaders into their country. Times have changed. Looking forward to reading your book.

John, My husband, Charlie Adams, and I have always held you up as someone who is doing God’s work in this terribly torn and sin filled place. Thank you to the Lord for equipping you.

Thank you for sharing your amazing experience in Russia, John. And thank you for your many years engaging Christian College students in the larger world. It was beautiful to see when they returned to campus how richly their understanding had deepened.

Thanks John,

Yours is a unique and essential calling. Your perspective is so valuable on the world stage right now. I have appreciated your books, classes, and lectures. Particularly striking to me here is the humble letter your delegation sent to USSR leaders and how it contrasts with today’s MAGA idolatry.

Fascinating. Thank you for telling of it.