In our family, I am the vacation planner. We decide as a family where we want to go and what we want to do, but I am the one who goes to work making travel arrangements, figuring out accommodations, and determining the daily itinerary of activities and attractions.

My itineraries are masterful — designed to maximize our experiences and ensure we take in all the sights at our various travel destinations. The problem: I often fail to build in enough time to eat. Instead, we are often scrambling to grab food when we can, supplemented by the stash of granola bars I keep in my bag. No time to sit down for a meal . . . We’ve got a world to explore!

Now that my kids are older, this has become a running joke in our family. “Are we going to eat this time mom or shall we prepare to starve?” To be fair, it can be challenging to find places to eat when you are in remote regions of a national park or when you are trying to catch buses, trains, ferries, or planes.

Still, I’ve begun to question my approach to vacations, wondering why I feel the need to jam our time together chock full of activities, why I inadvertently measure the success of our vacations by the quantity and quality of our experiences, and why our vacations leave us feeling not only spent but, in the end, more disconnected from the world around us and from others.

About ten years ago, I happened upon Walter Brueggemann’s Sabbath as Resistance, a short book that provides a piercing analysis of our current socioeconomic culture through the lens of the Exodus story in Scripture. In it, Brueggemann describes how an economy like ours of endless production and insatiable consumption shapes and conditions how we think about ourselves as human beings, reducing us and our sense of worth to what we do, what we accomplish, and how much we have.

Reading this book was like looking in a mirror . . . I recognized so much of my own anxieties, fears, and distorted perceptions of myself in his description. What became so painfully obvious was that I had so thoroughly absorbed the fallacy that we are what we do, that I had turned our vacation time, our opportunities for sabbath rest, into a list of experiences to consume. Instead of concerning myself with how to create an environment that encouraged deeper connection with each other and with the created world, I was focused on how to fit in one more hike or one more attraction.

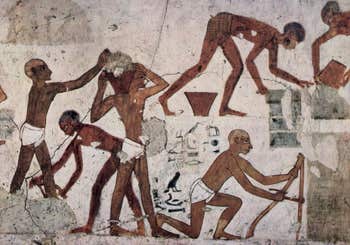

Brueggemann’s analysis of the biblical exodus as a rejection of Pharaoh’s rat-race economy of production and consumption was my “aha” moment. In calling his people out of Egypt, God was inviting them into a whole new way of thinking about their relationships with each other and the world, into what Brueggemann refers to as an economy of neighborliness.

In an economy of neighborliness, we are not reduced to what we do, acquire, desire, or build. Instead, we can be who we were created to be, who we truly are, that is, lovers of God and lovers of others. An economy of neighborliness is based not on the endless accumulation of personal wealth but on communal sharing and mutual responsibility. In such an economy, resources are not commodities to be exploited for personal gain but gifts to be received with gratitude and shared.

At the center of an economy of neighborliness is not frenzy, fatigue, and fear, but gratitude, rest, and trust, attitudes and postures that are cultivated through the practice of sabbath. Sabbath provides the necessary framework, or as Travis West argues in his new book, The Sabbath Way, an organizing principle for a life devoted to love of God and love of neighbor.

Sabbath rest reminds us that God is in control, not us, allowing us to let go of our to-do list and teaching us to trust God. Sabbath rest gives us time to spend with our neighbors in ways that foster deep connection and disrupt attitudes of covetousness and competition. Sabbath is the alternative to a soul-crushing culture of insatiable accumulation that has left us tired, empty, and alone.

We live in a nation that has lost a sense of neighborliness, of communal sharing and mutual responsibility. Neighbors near and far are perceived as a threat to our own well-being rather than friends and companions in mutual flourishing. Human beings are treated as collateral damage in the quest for power and wealth. Neighborliness seems like a quaint practice of years gone by. None of this feels good. So how do we resist being conditioned and shaped by such a system? How do we say no to reducing our lives to what we accomplish or what we acquire? What does it look like to be liberated from Egypt?

For Israel, the sabbath became a sign of the covenant that God established with his people (Exodus 31:13). The practice of sabbath marked Israel as God’s people and signaled that Yahweh was Israel’s God. Observing the sabbath became the alternative to insatiable productivity and consumption and ushered Israel into a different way of doing life together.

That invitation to sabbath rest is one that God freely extends to us as well. Together, as communities of God’s people, we are invited to embrace sabbath rest as an act of resistance to a life that leaves us tired, empty, and alone. To cultivate communities of goodness that serve as an alternative to an economy of insatiable production and consumption. And to welcome the gift of connection, community, and rest.

Soon I will start planning our next vacation. It’s slow-going, but I’m learning to let go of the to-do list, to build in more opportunities for simply being together, and to trust that God will bless our time together in ways that I can’t begin to ask for or imagine. So who knows? Maybe on this next vacation, we will have opportunities to linger over good food. Maybe we will even take a few naps. And in our sabbath rest, I pray we will rediscover in our life with God and with each other, God’s gifts of goodness, gratitude, and grace.

Header photo by Frankie Cordoba on Unsplash

Arc de Triomphe photo by Mika Baumeister on Unsplash

To-do list photo by Glenn Carstens-Peters on Unsplash

11 Responses

May I add a companion book, _Sabbath, by Abraham Joshua Heschel? He presents a similar vibe as he challenges post-war ’50s modern culture to just.slow.down.

https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/345500.The_Sabbath.

Agreed! Heschel’s work is such a beautiful introduction to Sabbath as a divine gift, a spiritual refuge, time to commune with God. Thanks for mentioning this!

Sabbath is the new civil disobedience.

This is so good! I continue to learn from your Brueggemann quotes and this idea of slowing down. I remember a work trip years ago with fellow CRC staff that included training for small group leaders – and when we began the trainer announced that we would now take about 3 hours to rest. Rest?? We hadn’t even begun. But we had all come from hectic schedules and travel, and that gift of time to relax and rest was amazing. I believe it made a difference in our time together. Another favorite book that I have in my library on Sabbath is “24/6: A Prescription for a Healthier, Happier Life”, by physician, Dr. Matthew Sleeth.

Thanks for the book reference, Diane. Looking forward to reading Sleeth’s book on Sabbath. Also, what a restorative way to begin a staff training!!

I relate to this, Amanda. We’ve learned some parameters for our family vacations as well. Our primary teacher has been our son with Down syndrome. There is no rushing that kid. He has no sense of time or urgency, for one thing, and when he’s tired he just sits down and won’t budge. We used to be able to throw him in a backpack carrier and keep going, but now that he’s 14 we just have to stop with him. I haven’t read Brueggemann’s book, but I imagine that living with our son would make many of his ideas seem a bit intuitive to us. Thanks for sharing.

Thanks for sharing this, Marie! I could learn a lot by hanging out with your son.

Thank you, Amanda. I know about overplanning, but since we’ve lived in Canada I’ve come to appreciate holidays as holy days, not merely vacations to veg out, but to savour: rest, ride, paddle, cook fun meals. Also, I’ve long been tickled by the odd etymological relationship between tavern and tabernacle. That came to mind the first time I heard Kris Kristofferson’s “To Beat the Devil,” in which he sang,

“So with a stomach full of empty and a pocket full of dreams

I left my pride and stepped inside a bar

Actually, I guess you’d call it a tavern.”

Love the closing lines of stanza 3:

“I ain’t sayin’ I beat the devil, but I drank his beer for nothing

Then I stole his song.”

Yup. Praise and worship in the tabernacle of a tavern.

Love this, Jim. Thanks for sharing. We too are learning to savor but boy, does it take discipline to stay in the moment.

Love this, Amanda!! Brueggemann’s book has been deeply formative for me as well. I remember how you encouraged me to give it a second read several years ago when I was initially creating my sabbath class, and I hadn’t connected with it the first time. His chapter on resistance to exclusivism shaped a really important part of my class and subsequently an important part of the book. So thanks for that!

Also, I was reminded a bit of Wendell Berry’s poem “Vacation” while reading your post. He doesn’t lament the thing you’re talking about directly, but it may at least give you some encouragement to slow down and be a bit more present the next go around. 🙂

Maybe we would rest more if we read the fourth commandment in Deuteronomy 5 instead of in Exodus 20. Instead of being based on God’s creation, the second time it is based on salvation history. It has a social and humanitarian motivation. Rest is a symbol of our freedom which is extended to slaves, aliens, animals, even the land elsewhere.