Editor’s Note: While Amanda Benkhuysen’s series of reflections on the work of Walter Brueggemann continues to run on Sundays, we present this personal remembrance of a friendship with Walter.

A sermon Walter Brueggemann preached saved my life.

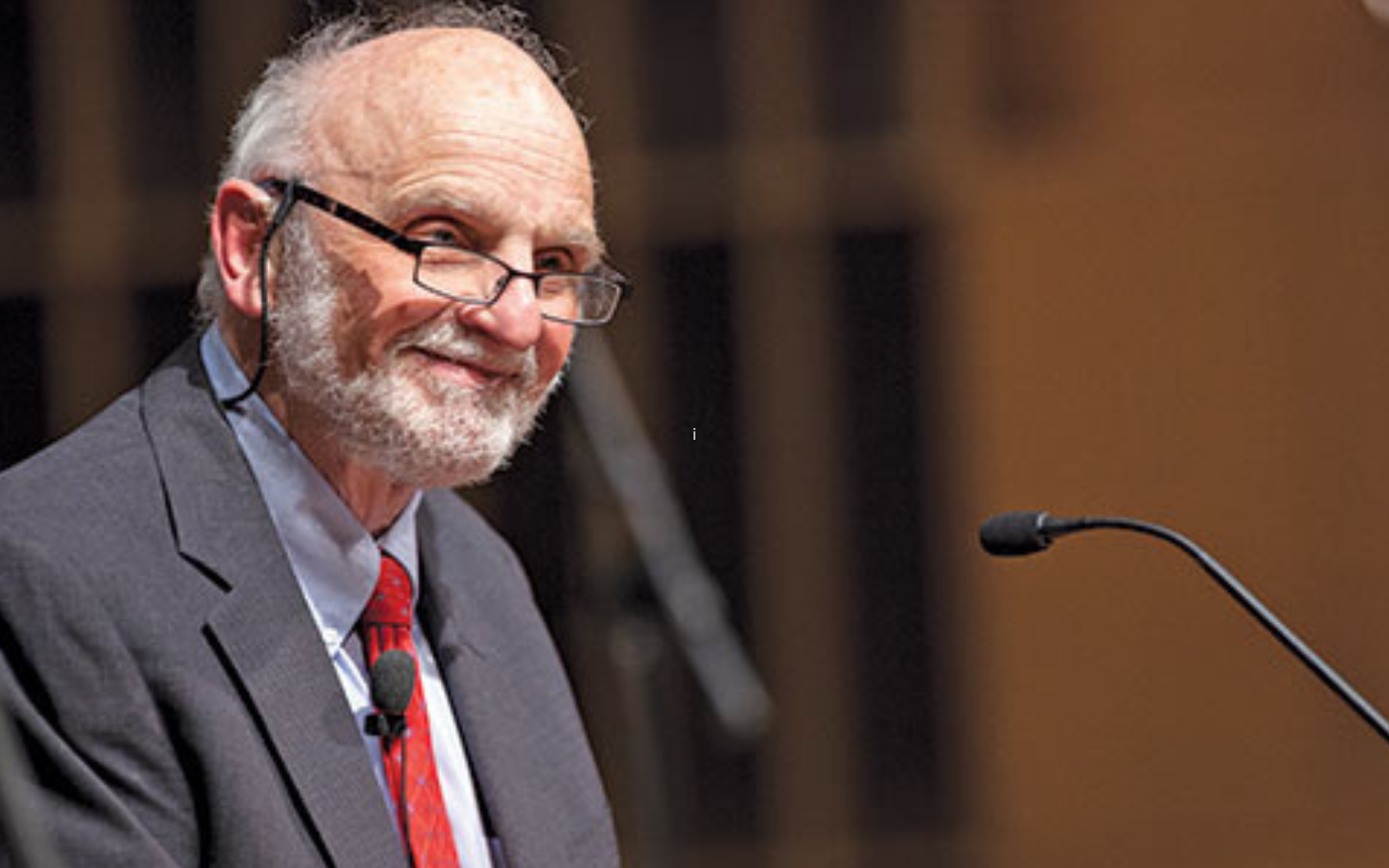

That sentence is neither a quip nor a figure of speech. Ironically, the sermon was entitled, The Secret to Survival. The text was Jeremiah 20. It was May 2002 at Fourth Presbyterian Church in downtown Chicago. Walter did not just preach from Jeremiah that day, he was Jeremiah. At the intersection of Walter, the text, the context of a preaching conference, and the Holy Spirit, my parched bones were reassembled and my spirit revived. For the first time in years of pain, light outweighed my darkness.

The message was quintessential Brueggemann: “Tell the truth of your pain to God, do not bear false witness, do not hold back, give it to God. Voicing pain is where all emancipation begins. Once spoken, don’t be surprised if you hear a voice say, ‘I am with you’.” I can still feel the breezes that meandered into that sanctuary; I can still hear the Chicago traffic so indifferent to what was going on inside.

The previous three and a half years had been a ministry nightmare. During that time, I had done 47 funerals as my congregation and community had multiple sudden tragedies including accidents, violent deaths, suicides, and murders. The nation was freshly coping with 9/11 and I was also dealing with two significant losses in my own life. It was all too much, and I had decided it was time to be done—not just with ministry, but with everything. Walter’s sermon saved my life.

At the end of the service, I waited in line for a private moment to talk with him. I didn’t want his autograph; I wanted to thank him. When I did, his cadence made his words sound like they were reluctantly rolling through a gravel driveway: “Well… it’s nice to know some of this stuff makes a difference ONCE in a while.” Up to that moment, I had not articulated the depth of my dark despair to anyone, including God. Walter had said that voiced and articulated pain, heard by another, would bring freedom. It did.

For the next several years, we stayed in touch. I participated in small retreats he sponsored, we corresponded, and we talked regularly on the phone. Over time, Walter was less the idealized sage-on-a-stage and a very human friend. He would ask about my children by name, track their progress in school and Little League, and be available for personal or professional calls. I knew things had shifted in our relationship more than a decade ago when he began calling me.

Walter would stay in our home when speaking in our area. My kids knew him merely as a friend of their dad who was kind and slept over while in town. Their teachers and professors were dumbfounded when my children would cite conversations with Walter Brueggemann in their papers. For the last decade or so, Walter would send me copies of his most recent books and I would tease him about giving our mail carrier a hernia. He would joke “It’s the same old stuff, just with a different name.” He was not afraid of self-deprecating humor nor was he ashamed of his shame. Shame was his chief fuel for being so prolific. Walter knew this in part, of course, but learned of its depth when Sam Wells wrote in the foreword to Walter Brueggemann’s Theological Imagination: A Theological Biography: “Walter retains the abiding shame, inhibition, and ambiguity attributable to the desire to please a mother impossible to please and a father he never wanted to feel small. Most people who’ve read his books or attended his lectures or sat under his sermons see Walter as a towering figure, missing only sandals and a crooked finger to be hectoring prophet the Old Testament. . . . Walter is very much a human being with his own family systems to experience and endure, all too aware of offering one’s true identity to a public that only wants to see you as a warrior for its causes.” (His father, August Brueggemann, was a pastor of the Evangelical and Reformed Church, a forerunner of the United Church of Christ. Brueggemann was born in Nebraska but the family moved often while he was child as his father moved from pastorate to pastorate.)

When he first read what Wells had written, Walter responded with astonishment and fury. However, after lingering for some time and talking with trusted friends over Wells’s insight, he embraced these initially unwelcome deep truths. To Walter’s credit, he not only signed off on the publication of Wells’s assessment for the biography but had a new hermeneutical lens for reading his own narrative. Walter’s son once shared with me “My dad was always peddling hard. There was always another degree, position, book or project to work on.” Rather than making Walter distant from his son, though, he added, “The crazy thing is that he was always someone I looked up to and he was always available to me.”

Walter was one who lived at his own crossroads of shame and grace, light and dark, brokenness and redemption. In Jungian terms, he befriended his shadow. In fact, Walter didn’t just embrace his shadow; he was pals with it. His living relationship with his own shadow deepened him and made his relationship with God both risky and urgent and filled with dynamic tension. Walter was impatient with those who preferred boxes for him, for themselves, or for God. Instead, he invited—and summoned—others to an edgy life in the tensions, juxtapositions, and paradoxes of Christian living.

Walter referred to himself as a “liberal Calvinist,” a moniker that frustrated liberals and conservatives alike. He was fluent in both conservative and liberal Christianity and fluid and oppositional when either group overly claimed him. When critiquing any strand of Christian tradition—whether on the left or right—he often said what others may have overlooked in an argument: “Jesus of Nazareth is still the guy.” As for what he ultimately believed, we once had a conversation about the resurrection of the body and he told me, “First and foremost, I believe the gospel in that regard. Second, I don’t believe there is anything in me worthy of resurrection as if I am somehow entitled to it. Therefore, I entrust my life and future life possibilities to God.”

I first read Walter in seminary and felt his writing made something come alive in me. When I shared my gratitude with the professor who assigned the reading, his response surprised me. Instead of saying something positive, he gave me a warning: “Be very careful with him, he comes from the higher critical school of interpretation. You need to use caution.”As a first-year seminarian, I had no idea what that meant. What I knew was that something and someone had stirred my imagination using scripture in a way that enlivened me. What I needed in that season of my life was not a warning but an opening and widening. Walter’s work did that. My professor’s cautions felt like a narrowing that was cutting me off from some of the life and energy I needed both personally and for ministry.

While Walter’s work was refreshing in seminary, revitalizing in the pastorate, and a lifeline in my crisis, his friendship is something for which I lack adequate words. I tried—especially in 2013, when Walter turned 80 and his pastor and family invited some friends to share written tributes with him. This was my chance! I wrote a page and a half detailing the specific differences he had made in my life, told him how grateful I was not just for his work but for him, and told him I loved him and that I knew the feeling was mutual. I borrowed his words as an introduction to my own: “Now pay attention ‘cause I worked hard on this!” (and I did!), and told him, “Walter, you will always be part of my narrative.”

In early June, I was at his bedside a few hours before his passing. I reminded him of how my story with him began—a story that became ours. I reminded him how much he meant to me, how much I loved him, and how important he has been for the church and its pastors. I repeated many of the things I’d written in 2013, including telling him, “You will always be a part of my narrative.”

I marked the sign of the cross on his forehead, embraced him, and said, “God be with you until we meet again,” and then left. I wept for nearly half the drive home. Walter packed so much life into his lifetime and gave me, the church, and its pastors so much.

All of us who loved him and his work must lament. We must. Why? We must articulate the pain of the loss of Walter Brueggemann in order that freedom and the energy of emancipation might come as we attempt to carry on what he began. We cannot expect to mirror the energy, life, or vitality that he shared without acknowledging our loss. That’s what he taught us.

He would say to pastors, “Stay at your most difficult and noble work. Get at it, and stay at it—and keep pressing on!” Sometimes, he’d write those words to pastors, and when he did, he would sign it, “In glad solidarity with you.”

For myself, and also for that legion of pastors, I say thank you, Walter. We love you and miss you.

11 Responses

Great stuff, thanks.

Thanks for this, Marc. Very thoughtful, heartfelt, and instructive for those of us who live in carefully constructed biblical-theological-confessional-emotional boxes which restrict and imprison us more than we imagine. I like my boxes, but they need to have permeable walls – flexible walls. Reading Brueggemann has helped me to keep the walls of my boxes from stifling me.

Thanks again for your words.

Wow, Marc,

What a tribute to Professor Brueggemann!

Makes me want to meet you here in Holland and share our journeys.

I recall how revered professor Eugene Osterhaven loved Central Park RCA and inspired hundreds like Professor Brueggemann!

You are carrying on his ministry here and now. So exciting.

I met him only twice, but he also left quite an impression on me, especially the first time he spoke at a Bread for the World conference in Washington DC, leading the whole assembly in chants of “Dayenu” (it would have been enough or it is enough) emphasising that with God there is always enough of life, food, etc. for all God’s children. His academic books are essential reading but so are his books of sermons and prayers. Currently, my wife and I are reading a daily devotional, Gift and Task, that I would recommend for anyone who wants to try shorter samples of his writing that still contain tremendous insight, wisdom, and just plain common sense about God & God’s word.

So inspiring and uplifting! Thank you, Marc. Gospel, scripture, grace, doctrine, imperfection, faith. It is all Dayenu. The sufficiency of God deserves more emphasis.

I’m glad to hear God has appointed you to serve at Central Park – I was there in the 2000’s. Now I know those good people had at least two pastors influenced by Walter Brueggemann’s perspective on Scripture. May Jesus bless you in your work and in your rest.

I love this SO MUCH, Marc. When I saw the title, it crossed my mind that I might see that Marc Neleson wrote this. Glad I was right. What a great piece this is.

Grateful thanks to you, Marc, for this poignant and powerful testimony. It brings back strong memories of the one time I met Walter Brueggemann when he spoke on the importance of the lament psalms at Calvin in 1993; “The Friday Voice of Faith” was so important then (and now!) for worship that we provided a summary in Reformed Worship (RW 30).

As a congregant under both Dave Landegent and Marc Nelesen at Central Park RCA, those who have ears to hear have been blessed with the unspoken influence of this prophet among us. As a late-to-the-party Brueggemann neophyte— thanks to Marc—it took weeks, nay months to absorb the depth and richness of his “prophetic imagination.”

In this Church teetering, “post-truth” era, we need more than ever his message to thunder down from our collective pulpets.

Marc, you could indeed be Walter’s “true son in the faith” much like Timothy was to Paul. I first learned of Walter through you, and your ministry reflects his. Thank you for this loving and powerful tribute.

Thanks for sharing about your personal connection and friendship with Brueggemann, Marc! And I’m so glad to hear that your friendship with him was restorative and healing for you.