Jesus promised Peter that he would be the rock upon whom Jesus will build his church, and the “gates of hell shall not prevail against it” (Matt. 16:18). This assurance does not mean, however, that the church will not face painful, disruptive change.

Yup, and here we are in the midst of painful, disruptive change, not only in the little denominations RJ readers know, but across American expressions of the church. As we weather these disruptions, we hear a lot about “decline.” For many across the spectrum of Christian traditions, decline means empty pews and aging membership and budget struggles and buildings that desperately need a new roof which we can’t afford. We try to blame ourselves or blame each other. Not enough zazz in our worship services? Not a cool enough youth group? Too strict or too loosey-goosey in our positions in the culture wars? Are we the faithful remnant or the ones who finally blew it?

Some churches might boast they are actually growing because of their [pick your preferred virtue here]. And I would argue that membership numbers are not the only measure, either of decline or of thriving. But overall, if you want to define decline in terms of numbers, American churches are “declining” across the board. Why?

We can attempt to answer that question any number of ways, but sociology can offer some helpful insights. I read Notre Dame sociologist Christian Smith’s new book, Why Religion Went Obsolete, earlier this summer, and I found it breathtakingly explanatory for much of what I’ve witnessed in my own experience across the past six decades.

Smith’s title is provocative, but Smith is a Christian himself; he’s not trying to rejoice over decline, only to understand what’s happening. He begins by accounting for what we term as “decline,” using some traditional measures of religiousness: affiliation and church attendance, among other things. The data is clear: “each successive generation born across the twentieth century was noticeably less strongly affiliated with religion than the next older generation. We can see a total decline among those reporting strong or somewhat strong religious affiliations from roughly 65% reported by the Lost Generation down to about 20% by Generation Z.”[1]

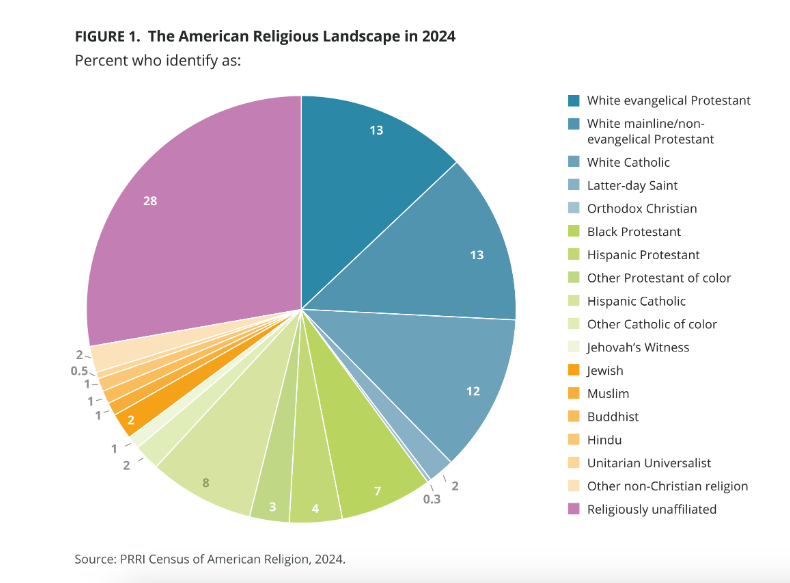

Other indicators show similar results: The Millennials, born 1981-1996, started out less religious than their elders and declined from there. Gen Z, born 1997-2012, even more so. “In sum,” writes Smith at the end of this section, “traditional religion has been losing ground among Americans, especially younger ones, no matter how you measure it: affiliation, practices, beliefs, identities, number of congregations, and confidence in religious organizations have all been declining.”[2] Surveys done in 2023 and released in 2024, after Smith’s book was in production, confirm this trend. The religiously “unaffiliated” now comprise 27% of Americans. That means people unaffiliated with a particular religious group make up the largest segment of Americans, now double the size of each of the three next-largest affiliated groups: White Evangelical Protestants (13%), White mainline/non-evangelical Protestants (13%), and White Catholics (12%).[3]

What’s happening? Well, Smith’s argument is 373 pages long, plus footnotes, so: it’s complicated. These declines in numbers are not the result merely of the church’s failures, nor can we blame vicious secular humanism promoted by those liberal university professors peddling wokeism. That’s not it. We see in the data that a lot of people who have left traditional religion still believe in God and consider themselves spiritual. Instead, Smith argues for a complex of reasons, most of them not the church’s fault (although some are). In essence, he argues, we’ve experienced a major zeitgeist change, resulting in a massive cultural mismatch between traditional church and the way people imagine themselves, their world, and how to get through life.

Smith examines numerous major sociological trends since World War II, but some of the most interesting ones to me had to do with “triumphant mass consumerism,” “intensifying expressive individualism,” and “declining participation in face-to-face membership organizations.” Also with the rise, especially since the 1980s, of neoliberal economics and a massive transfer of wealth to the super-rich. Surprisingly—or maybe not—church decline has a lot to do with economics.

These trends and others, taken together, have shifted our very anthropology: we now think of ourselves and behave, largely, as consumers with preferences. At the same time, regular people have had to struggle more and more to make it economically. So in each successive generation, we work harder and longer, we move around more, we have fewer children because children are expensive and how will we pay for childcare? We just don’t have time for church or volunteering. Meanwhile, the digital revolution has intensified our consumerism and further diminished our face-to-face connections. All of this, Smith observes, constitutes a “habitat loss for religion as a species.”[4]

In sum, we have reached a fundamental cultural impasse, Smith writes. Because all traditional religions “despite their vast theological differences, would agree that the neoliberal view [of human nature] is not only wrong but also delusional. For traditional American religions, humans are divinely dependent and socially interdependent creatures who inhabit a morally significant universe in which they are on a quest to realize, with divine aid, their spiritually and morally higher selves, the aim of which is to enjoy flourishing lives in communities of peace and love that reside under the governing care and judgement of God.” However, neoliberalism reduces us to “efficient producer, rational exchanger, and desiring consumer.” It’s tough to inhabit both these worldviews at the same time.

Other trends have to do with trust. Especially since 1991, young people—all of us, but especially young people—have learned to distrust institutions of all kinds. Yes, the church is at fault here for its hypocrisies and scandals. One of the most grimly disheartening sections of the book is the five-page chart in the middle mapping a florid swamp of clergy and denominational scandals from 1985-2017. But Millennials are disillusioned with more than just the church. Millennials have lived through 9/11, the 2008 economic downturn, the “war on terror,” Iraq and Afghanistan, fights over LGBTQ+ rights and acceptance, the Covid-19 pandemic, #metoo, Black Lives Matter, the MAGA movement, and a planet heading toward climate collapse. One scholar refers to Millennials as “Generation Disaster.”[5]

No wonder young people are deeply suspicious of institutions, prosperity promises, any effort to control or police people. They just want to get through life, be decent to each other, and not get judged or controlled. I see this in my own children, and in myself. Born in 1965, I am the first cohort born among the post-Boomers. I have lived my life in institutions, but always with some hesitant distance. Ron and I have several advanced degrees, and we have both worked jobs all our lives to maintain roughly the same lifestyle that my parents achieved with high school diplomas and one income. My children and their spouses are Millennials or Gen-Z. They trust nothing. They struggle to make it economically, despite their excellent educations. Moreover, despite being raised by super-devout parents in a healthy religious environment, they do not go to church. They’re not hostile; they just … don’t. Many of our church friends say the same about their adult children. We all agonize over how we failed. But maybe we didn’t. Maybe we’re just swept up in a perfect storm.

In one of his more devastating paragraphs, in the section titled “Perfect Storms Converging,” Smith posits that traditional churches simply haven’t adequately perceived or addressed the feeling of doom that pervades younger generations. Our religious systems were built for a different era, and we haven’t adjusted. “Of all the institutions in the United States that possessed the internal resources to take seriously Millennials’ darkness, despondency, and semi-suppressed anger, it should have been religion. Who else owns the language of and has spent countless millennia wrestling with evil, depravity, brokenness, damnation, suffering, redemption, hope against hope, and a meaning to life beyond the horizons of the present?” he asks. Instead, young people observed overly cheerful megachurches, scandal, internal fights over issues they are long past (like LGBTQ+ acceptance), and more. Smith concludes: “Religion may have had a chance to connect, but it missed by a mile.”[6]

In case you’re wondering what Smith predicts for the future: he refrains. He does say that he doesn’t see indications in the data that these trends will shift dramatically anytime soon. However—and he says this—you never know.

I have been recommending this book to every pastor and educator I know. Smith uses sociological data to illuminate critical aspects of the American religious experience in the last 30-40 years, with a particular eye to younger people. Perhaps we could arrange an RJ blog-round-table of responses to Smith’s observations.

I’m not convinced that every period of change amounts to “decline.” Crisis can also lead to renewal. To discern where the Spirit may be leading the church right now, we need to observe soberly, patiently, and wisely where and when we are. This book can help.

Image source: Tony Cenicola/The New York Times

[1] Smith, p. 25.

[2] Smith, p. 34.

[3] https://refugianewsletter.substack.com/p/refugia-newsletter-75

[4] Smith 85.

[5] Smith, p. 211, quoting Karla Vermeulen.

[6] Smith, p. 214.

11 Responses

Thank you so much. Very helpful. In prior decades, Masterpiece Theater on PBS, which was considered high-brow television, with all those British imports, was sponsored in New York by the Syms clothing store chain. Their sponsorship ad was choice: “An educated consumer is our best customer.” PBS appeals to educated consumers far more than church does. Neo-liberal culture is the same thing as entertainment is the same thing as marketing.

Thank you for this, it’s interesting and thought-provoking. It makes me wonder whether there’s a connection between regular church attendance and active involvement in ministries such as food pantries, caring for the homeless, providing affordable housing, or delivering meals to those in need. If I were to guess, I would say there is. Does Smith agree?

Great question. Smith does not address this directly. I do wonder if churches have too long considered worship services the entry point, when what would actually bring people into community is opportunities to serve–outside the walls of the church, as you suggest.

Thank you Debra. This was very interesting and informative. Greatly appreciated.

Daryl Van Tongeren’s book “Done: How to Flourish After Leaving Religion” also offers some solid data on why people leave religion.

I can’t help wondering, beyond all the well researched sociology, whether the decline of institutional Christianity is not, in some sense, providential. Conformity to the crucified Christ, after all, cannot entail a church brimming with social, political and institutional power. It may be that such a situation as ours is what finally prompts the church to find its voice as an alternative to the “totalizing ideology” Walter Brueggemann called “technological, military consumerism.” Doing so however would necessarily entail letting go of our deep anxiety about “decline” and listening again the alternative voice from elsewhere found, you guessed it, in the Bible.

I agree completely, Tom. Thank you.

Thank you for this. Sobering and challenging. Not only pastors but also church council members should read the book and engage in focused discussions.

Smith specifically dates the cliff’s edge at 1991. Birth of the internet and end of the Cold War. The great European secularization also coincides with the demise of their empires in the 1950s-60s. Another factor worth exploring….

Thanks for this, Deb! This has been on my “to-read” pile for a bit, and this article is prompting me to insert it at the top 🙂

As a former Christian always find it interesting to listen to why people think so many of us left. I’ve yet to meet a pastor or any Christian giv3 q very good answer. If you want to know why people left you should ask them.