Many moons ago when I was still serving in campus ministry, a student commented to me that the way God had been described to him in church and in catechism classes made God seem distant, detached, and disconnected from us and from this world.

God was characterized as holy other, transcendent, omnipotent and omniscient, standing safely above and apart from God’s fallen and sullied creation. The impression given was that this God would not, even more, could not be close to us, present to us, unless sin was dealt with first. Our being made righteous and our purity was the key to God’s active love and care for us.

“I’m really struggling with what it means to love such a cold and distant God.” the student said. “But more than that, I worry about what veneration of such a God who prioritizes purity and righteousness over relationship would do to me. How this belief would shape my heart, my own approach to faith, and my attitude toward relationships.”

No doubt at the time, I fumbled through a response, probably highlighting other attributes that nuanced this stark picture of God and likely pointing out that Jesus is God in human flesh, entering our world in all its messiness in a radical act of love for humanity.

Since that moment, I’ve wondered about this question — how our view of God impacts and shapes our hearts. How it impacts our understanding of what faithfulness looks like. How it shapes our attitude and approach to relationships with others. I mean, if our primary image of God is one where we need to reach a certain level of righteousness, where we need fixing up before God can be present and in relationship with us, it would make sense that we would put enormous energy into policing our behavior and the behavior of others out of fear of displeasing God and driving God away. Right belief and right practice, as determined by the individual believer or by a community of believers, would surpass relationship. The quest for purity would take priority over people.

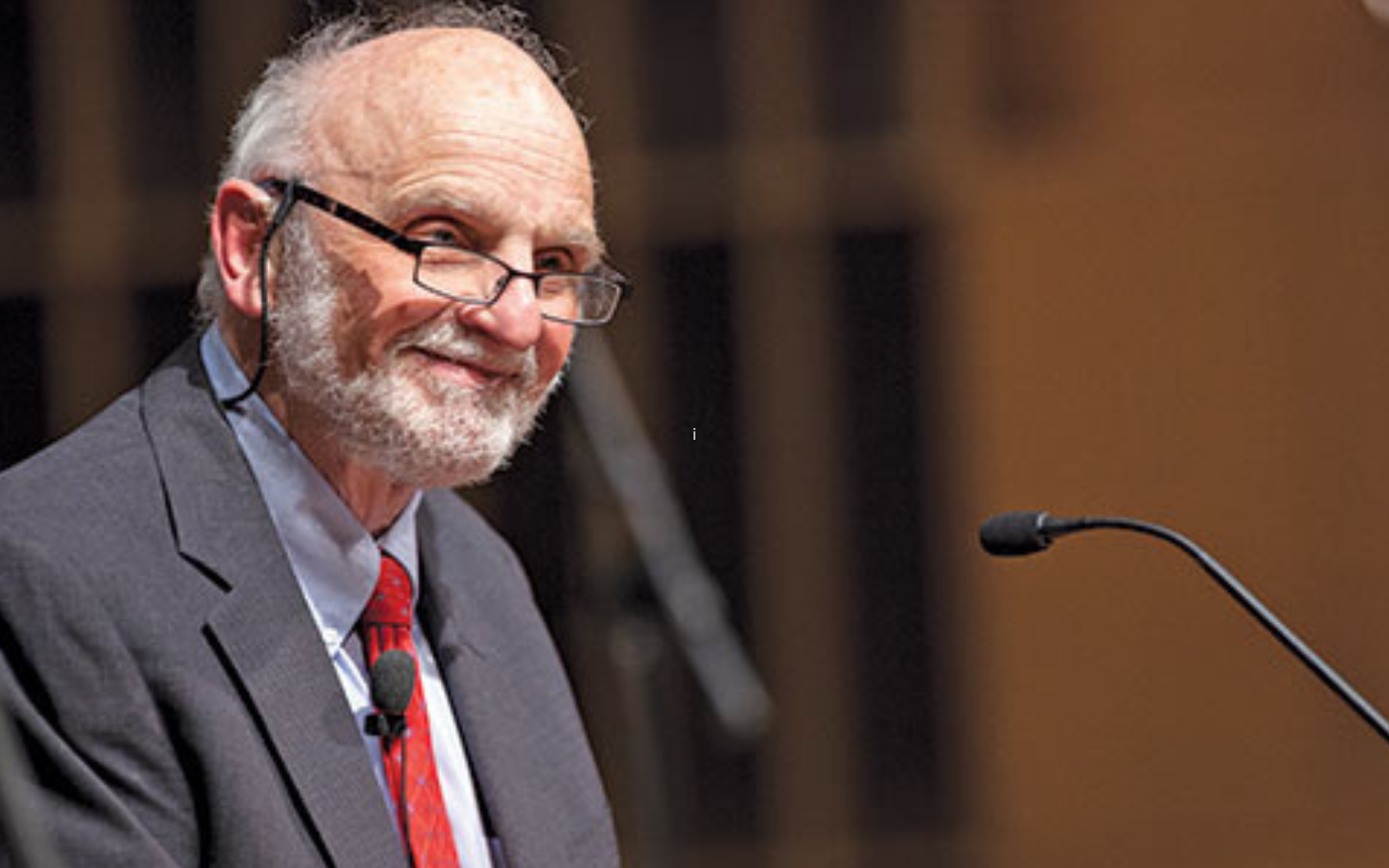

But what if, as biblical scholar Walter Brueggemann suggests, the primary category and organizing principle for understanding the nature and character of God is not transcendence or holy otherness or omnipotence, but covenant relationship? How does that change the way we think of God, what it means to be faithful, and our attitude and approach to relationships with others?

To be clear, it’s not that Brueggemann eschews other attributes of God like God’s holiness or omnipotence. It’s just that he contends that what primarily defines God as Israel’s God and by extension our God, is covenant fidelity, rooted in God’s faithfulness and steadfast love. Other attributes that describe God — goodness, power, holiness, justice, etc. find their significance and meaning in relation to this fundamental quality of God as a relational God who binds himself to his people and his world in an act of covenant fidelity.

This is not to say that God is okay with sin as if it doesn’t matter. Throughout the Bible, God is described as being hurt, disappointed, and outraged by Israel’s covenant violations (hardly the image of a detached, disinterested God). But the Bible also describes God’s love and compassion winning over his anger again and again, compelling God to renegotiate and reestablish the covenant with Israel in ways that create a radical newness for a future together (Eg. Exodus 34, Jeremiah 31:31-34).

Sin doesn’t end the relationship because God is God, making a new way where there seems to be no way. A way wholly dependent not on Israel being righteous enough or pure enough, but on God’s own commitment and love for Israel. Consider Hosea 11. What starts with a litany of Israel’s sins and God’s profound frustration with his wayward child quickly turns to

How can I give you up, Ephraim?

How can I hand you over, Israel? . . .

My heart is changed within me;

all my compassion is aroused.

I will not carry out my fierce anger,

nor will I devastate Ephraim again.

For I am God, and not a man—the Holy One among you.

Hosea 11:8-9

God knows that Israel will violate the covenant again and yet, continues to invest in the relationship, continues to turn his face toward Israel, continues to choose love, a posture which ultimately leads to the cross, to God giving up everything for the sake of relationship with us and the world.

It’s not hard to imagine how this characterization of God might shape our hearts, our faith, and our relationship with others. How God’s commitment to relationship, God’s covenant fidelity might cultivate in us a greater connection and love for God, a more profound understanding of grace, and a deeper response of gratitude to a God who is for us and who is actively present to us, holding us in his care.

I imagine it would also encourage in us a posture of love, grace, and neighborliness toward others, relieving us from the task of policing right belief and right practice and freeing us to model commitment, patience, and long-suffering in relationships. To reach out a hand or hug even to those who hold beliefs with which we disagree.

Maybe in this season of polarization and division, this feels too hard. But God’s covenant fidelity toward us ought to provide us with hope not just for a world where God is with us and for us, but where we can be with and for each other.

9 Responses

“God knows that Israel will violate the covenant again and yet, continues to invest in the relationship”

What a beautiful way to interpret his Mercy and Grace. A model to try and live out.

Thank-you Amanda,

I love the call to recognize God as a God of relationship and the call for us to emulate that in our own lives, to be that for others.

I also really appreciate that you have used God as the pronoun for God throughout the essay. God is bigger than the limits of the English language.

Amanda, thanks for your elaboration of God as a God of relationship, of “God giving up everything for the sake of relationship with us and the world” (as in John 3:16, for God so loved the cosmos.) I believe these two vertical relationships of God to humans and God to the world also define the two horizontal relationships of humans to humans as one of love and service, and of humans to the world as one of stewardship and caretakers of the world. Both are being challenged in our present self-centered and power hungry world.

Thank you so much for highlighting this fundamental conviction of Brueggemann and the huge difference it makes in not only how we see God but also how we live with our neighbor. I often ask myself when dealing with a difficult moral question, What do I fear more when I stand before God in that day of days? That God will say to me, Duane, why didn’t you do more to call sin sin and keep the church pure and keep the world out? Or that God will say to me, Duane, why didn’t you do more to help this marginalized person or group who were suffering at the hands of the church and society? What about my love for the outsider wasn’t clear enough to you?

This is great. I learned to view God relationally when I was a teenager in the Jesus movement days of the early 70’s. It has been a tremendous fertile soil for my faith in God, and it’s why I gravitated toward Barth and Brueggemann as I grew in understanding.

I’m 3/4 of the way through the book “A Gentler God” by Doug Frank, and he writes about this topic in a powerful and moving way. I took a break from that reading and found reading your post a wonderful serendipity.

I think one of the first things God says about Godself goes something like, I am the God of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob.” Seems like a relational God to me.

Thanks Amanda

I appreciate this understanding of God , but what about Hagar and Ishmael and Esau? I don’t know what to do with that part of the story.

Desmond Tutu says, “There is nothing you can do to make God love you more and there is nothing you can do to make God love you less. God’s love for you is infinite, perfect, and eternal…” It’s all grace and then our gratitude.