I’m not a numbers person.

As an English teacher, literacy consultant, and writer, I spend most of my time turning over words and their meanings. But this back-to-school season, I find myself puzzling over math instead—trying to make sense of a few problems that won’t leave me alone.

Before we begin, I want to offer a bit of context—something my best teachers always said could be helpful. Twenty years ago this fall, I stood in front of my very first eighth-grade class. I was nervous, spoke far too quickly, and felt a little like I was still just “playing teacher,” the way my sister and I used to do for hours in our basement. Yet as 25 to 30 middle-schoolers filed in each hour, found their seats, and turned their eyes toward me, I became acutely aware of the trust that had been placed in my hands.

Two decades later, I still work in education, but instead of a classroom teacher, my primary responsibility is to work side-by-side with educators who care deeply about their students—as both humans and learners. From that perspective of supporting teachers and honoring the hard, important work they do, I offer these story problems that could use our collective thinking to solve. Especially from those who identify as followers of Jesus, because how we approach these problems reveals not just our math skills, but our understanding of love, justice, and the kingdom of God.

Problem 1:

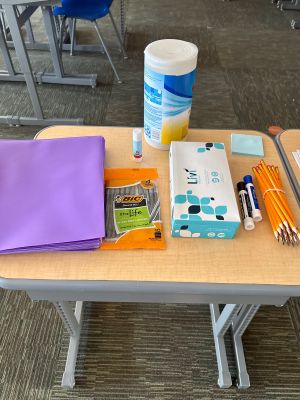

A friend, let’s call her Samantha, teaches middle school science in a nearby urban district. As she reported to her district professional development meetings a couple of weeks ago, she was given her supplies for the year: a handful of pencils, two dry erase markers, one pad of post-its, one box of tissues, a package of pens, one glue stick, one container of disinfectant wipes, and a handful of folders.

She has 132 students.

According to U.S. News & World Report, 62.5% of the students in her district are economically disadvantaged.

Question: What does it say about our society that our schools with families that report the lowest socio-economic levels often are given the fewest resources? Do we expect teachers in these districts to subsidize the cost of meeting students’ needs? What, as Christians, might be our response?

Problem 2:

In the state of Michigan, where I live and work, a state budget has not yet been passed. Although the state has a statutory July 1 budget deadline, there’s no penalty for missing it, and the final hard deadline isn’t until September 30. As a result, while lawmakers continue to negotiate, schools are forced to begin the academic year without clarity on their funding, making it nearly impossible to plan responsibly for staffing, programs, and resources.

Adding to this complication, as of last school year, Michigan was one of eight states to provide universal meals to students — all students, regardless of economic status, had access to free breakfast and lunch. It’s commonly understood that students learn better when their stomachs are not growling. Research also shows that universal free lunch is more effective than the usual free and reduced-price lunch model because it takes away the stigma, better addresses food insecurity, and ultimately saves money—by cutting down on school paperwork (chasing down parents to pay their kids’ hot lunch bills) and lowering food costs for all families.

The Michigan School Aid Fund was 24.3 billion dollars in 2023/2024. The cost to provide free breakfast and lunch to any students who chose it was $200 million, or 0.82% of the total budget. That’s equivalent to taking a family out to dinner at a restaurant, having a bill of $100, and having 82 cents itemized on that bill as the charge to feed the children at the table.

Failure to pass a new state budget by the end of this month jeopardizes funding for Michigan’s universal free school meals program, potentially forcing districts to stop providing free lunches to all students starting October 1, as funding from the state is crucial to continue the program beyond that date.

Question: If it costs less than 1% of a state’s school aid budget to ensure no child goes hungry, what might be the arguments for withholding it? What, as Christians, might be our response?

Problem 3:

I was a college student when our nation was stunned by the news of the Columbine Massacre. Thirteen years later, my oldest son was in first grade when we watched in horror as first graders were killed at Sandy Hook Elementary. I wept as I imagined being their parents, being their teacher.

For years afterward, I taught in the first classroom off the main hallway of my middle school. During lockdown drills, I couldn’t help but worry that if the unthinkable ever happened, my room would likely be the first to be targeted.

Last week, a friend texted to ask how I was holding up after the latest shooting in Minneapolis. I’m embarrassed to admit I hadn’t made myself read or watch much of the news. I feel numb—tired of shedding the same tears and hearing the same familiar platitudes.

Since Columbine, it is estimated that there have been at least 488 school shootings in the U.S., resulting in thousands of deaths and injuries (Educational Fund to Stop Gun Violence). Between 2009 and 2018, the U.S. had 57 times as many school shootings as all other G7 industrialized nations combined (Canada, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, and the UK).

Question: If we truly want to address the issue of school shootings, what does action look like? What, as Christians, might be our response?

I am interested in answers to the three problems above, but am under no illusion that they can be solved with simple words or calculations. They deserve action.

And now, true to being an English teacher, I conclude with a brief, numbers-free story:

I recently attended a conference with the purpose of exploring how to make school more relevant and meaningful for students in middle and high schools. The most powerful part of the day was a student panel, when an auditorium of educators simply sat and listened to teenagers tell us about their experience as students.

The words of one student still ring in my head: “We don’t want teachers who teach a lesson and then sit down at their desks: if you want us to be engaged, you need to be engaged.”

Perhaps those words have a familiar ring because it’s a message I was taught over and over as a child: “Your actions speak louder than words” or “faith without works is dead.”

5 Responses

Thanks for this. The situation is even worse in Kenya where budgets are much lower and also not sent in full.

#1 Yes, we seem to expect teachers to spend their own money on school supplies, see this article from Huff Post: https://www.huffpost.com/entry/teachers-fall-spending-out-of-pocket_l_68a781d0e4b0ab862cb1a78e?origin=home-life-unit Most are spending several hundred dollars and a few spend a few thousand dollars.

#2 Why withhold the money for food? Petty partisan politics is probably the reason for not approving it on time.

#3 What would action on gun violence look like? Gun control like just about every other country in the world has.

As to what a Christian response to these issues would look like, that is a good discussion to have but looking at the list I don’t think a Jewish, Buddhist, Muslim or even a humanist response would be that different. Let’s just do it!

Dana,

Thanks for shining this bright light on these sad stories. Seems that the people in power, those with all the money, are much more interested in promoting artificial intelligence in schools rather than promoting the education and well being of actual children. Thanks for being a great teacher and educational leader, Dana. We need you!

Excellent, as always.

But I really don’t believe what you say: That you are not maybe so good at math! This is a smart, precise calculation of the hard numbers. You also possess the gift of pastoral precision in identifying and tracking the human heart, and a prophetic ability to reveal The System of things as relates to Christianity.

Thank you so much for doing this

Our daughter teaches art to elementary school students, most from non-privileged environments. The school is prepared for an assault by ICE. Daughter M needs supplies. She buys them, the money coming from her pay, and we save anything she might be able to make use of.

Dana, you have from day one in front of that class summoned the courage to teach each student, never an anonymous “class.” Your writing embodies that: we start to read and by the third sentence the words have disappeared and you are sitting beside us talking with us. Thank you. You are a gift to us.

Thank you for this excellent post. As a newly-elected school board member in our district, the reality of the numbers and how they impact students is really hitting home for me. I’m grateful that our state, New York, now offers universal meals to students, but as you’ve pointed out, most states don’t. And while our district for the first time this year is supplying K-8 students with all their school supplies, so many districts don’t or can’t. How indeed should we, as Christians, respond? One small part of the answer: our local suburban church has come alongside one of the urban schools to partner and provide donations, volunteers, and various forms of support throughout the year. What if every church were to do this? I’m sure it would have a significant impact. But ultimately, we all need to be voting for legislation that truly supports the needs of public school teachers and students. And it’s long past the time when we should have enacted gun control. The school shooting situation is tragic and mind-numbing. It’s more crucial now than ever that we not capitulate to the numbness, rather praying, acting, voting, urging others to vote, and protesting, all as we are able. Again, thanks for your excellent post!