Editor’s Note: Jared Ayers’s book You Can Trust a God With Scars was released on September 9. We are happy to share this excerpt with permission of NavPress.

My wife, Monica, and I have very different tastes in film, television, and literature, and mine tend significantly darker than hers. One evening several years ago on summer vacation at the Jersey Shore, after tucking our children into bed, I suggested we give the award-winning crime-noir television series True Detective a watch together. She made it ten minutes or so before informing that if I wanted to continue watching, I’d be doing so alone.

And I did.

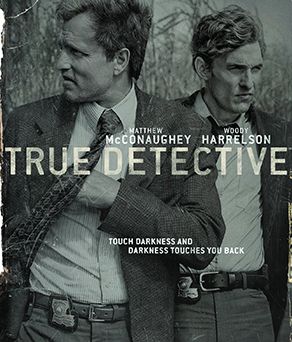

I binge-watched the eight episodes of True Detective’s inaugural season over the next thirty-six hours or so. Set in Vermilion Parish, a backwater precinct in rural Louisiana, the show centers on the relationship of state homicide detectives Marty Hart (played by Woody Harrelson) and Rust Cohle (played by Matthew McConaughey). Cohle is both intelligent and deeply troubled and has just transferred to the area after working undercover on a narcotics unit in Texas. His philosophizing and haunting nihilism immediately grate on Marty Hart, a lifelong local whose uncritical adherence to Bible-belt Christianity papers over his midlife restlessness, gnawing appetites, and marital infidelity. Harrelson and McConaughey’s chemistry create complex characters who over the arc of the series bristle at, cross, and eventually embrace each other.

One of my favorite moments of the series unfolds as Cohle and Hart set out to solve the murder of a young prostitute. As they follow leads, they stop at an outdoor revival service. Standing aloof at the edge of the tent, Rust Cohle surveys the crowd, scowling, and says: “What do you think the average IQ of this group is?”

Marty is confounded: “What do you know about these people?” To which Cohle, continuing to look around, deadpan, replies: “Just observation and deduction: I see a propensity for obesity, poverty, a yearning for fairytales. Folks putting what few bucks they do have in the little wicker baskets being passed around. I think it’s safe to say that no one here is going to be splitting the atom, Marty.”

They continue to argue under their breath at the edge of the crowd, and Cohle presses: “What’s it say about life that you’ve got to get together, tell yourself stories that violate every law of the universe, just to get through the day?”

They continue to argue, and before he walks away, Marty turns to Rust and remarks, “Well, I don’t use ten-dollar words as much as you. But, for a guy who sees no point in existence, you sure fret about it an awful lot.”

This is a book for those who see no point in existence.

This is a book for those fret about it.

And this book is for everybody who does some of both.

For much of my pastoral life, I’ve conversed in living rooms, at park benches, and in bars and cafés with people wondering about Christian faith, curious about what it would mean to become a Christian or struggling with whether they can stay one.

The questions we ask in the borderlands between faith and doubt are as old as humanity. And many of them are written right in to the text of the Scriptures. Listen, for example, to the ancient prayers set at the center of the Bible, the Psalms. Christians believe that Scripture is “the word of the Lord,” God’s discourse to the world in Christ Jesus. But the Psalms, uniquely, are both Holy Scripture and human praying—God’s Word to us, and our words to God.

And these canonized prayers gather up the big questions we ask and bring them to honest expression.

There are the anguished prayers of those who wonder if God’s forgotten them:

How long, O LORD, will You forget me always?

How long hide Your face from me? (Ps. 13.1-2)

And there are invocations that name the cruel unfairness of life—how it is that the corrupt enjoy lives of ease while good people suffer:

I envied the revelers,

I saw the wicked’s well-being:

“For they are free of the fetters of death,

And their body is healthy.

Of the torment of man they have no part,

And they know not human afflictions.” (Ps. 73.3-6)

There’s even the canonized cry of someone who feels forsaken by God entirely, who screams their supplication up at a silent sky and hears nothing in return:

My God, my God, why have You forsaken me?

Far from my rescue are the words that I roar.

My God, I call out by day and You do not answer,

By night—no stillness for me. (Ps. 22.1-3)

It is this derelict outburst that Jesus himself prays, in fact, as he comes to his end on the cross: “My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?” Jesus, who we Christians believe to be the human embodiment of the God we pray to, prays this very outburst of honest anguish. In his life, the masses flocked to Jesus for answers; but at the end, Jesus died asking our questions.

Doubt and disbelief are there, as well, from the earliest Easter beginnings of the Christian movement. In the Gospel accounts of the first Easter morning, a solemn parade of bleary eyed mourners make their way to Jesus’ tomb in the predawn blackness. In Luke’s version, several women arrive at the tomb with burial spices and embalming ointments, intending simply to offer their Teacher the dignity in death he was stripped of in his cruel crucifixion. But they don’t find what they expect (the body of Jesus), and they discover what they couldn’t have expected: two angelic figures, dressed in dazzling light, making the astonishing announcement that becomes the heart of the Christian gospel: “He is not here, but has risen!”

The women run, breathless, back to the eleven disciples who formed Jesus’ inner circle and who would go on to comprise the leadership of the Christian church. And what is their first response to the good news of Easter? “These words seemed to them an idle tale, and they did not believe them.” English translators are actually kinder to the disciples here than St. Luke himself is: In Greek, the language this part of the Bible was originally authored in, the word often translated in English as “idle tale” is lēros, which means something more like “BS.” The disciples, who became the first believers in the risen Jesus, were first the first disbelievers in Jesus.

Several years ago, someone stirred up controversy on Yale University’s campus by placing a cross on its grounds during Holy Week, replacing the Latin letters “INRI” traditionally found in Christian artwork (which mean “King”) with the letters “ROFL” (slang shorthand for “rolling on the floor laughing”).The cross created the predictable controversies about culture wars and free speech, but when I read this story, I was struck by the irony that this was actually closer to the initial response of the first Christians themselves to the Christian Gospel.

“Lēros.”

“BS.”

“Fake News.”

“ROFL.”

Black & Brew

In our first years in Philadelphia, my family lived in a two-bedroom, five-hundred-square-foot Trinity-style brick row house tucked into a narrow side street in East Passyunk. Our dog, Baxter, and our toddler, Brennan, occupied one bedroom, which left Monica and me, our newborn son, Kuyper, and our church’s “office”—my laptop, a home printer, and a few boxes of documents—to share the other room. Space was scarce to go over my sermon notes, so I’d begin many of my Sundays at a neighborhood café. In the stillness of Sunday’s early hours, I’d slide out of bed and attempt to tiptoe my way down our creaking stairs and across our old oak floors without waking one of our kids. After escaping through the front door, I’d walk the tangle of narrow South Philly streets east and south to the Black & Brew, which sat just a block up the street from the neighborhood square on Passyunk Avenue.

I’d enter as they’d open for the day at 6:00 a.m., and spread my notes, Bible, huevos rancheros, and an Americano with cream across my usual table in the back of the café beneath the bay window. Most of those Sunday mornings, there were just three of us in the Black & Brew as the sun rose and streamed across the dense, sleepy neighborhood: the woman working the early shift, barista and chef for the few customers who might wander in at that hour; me, nose buried in Bible, books, notes—and Daniel.

Daniel would usually sit at the bar, perched attentively over a plate of eggs Benedict and a cup of hot, black coffee, scruffy beard tracing a slender jawline that just barely escaped the shadow of his herringbone flat cap. He was finishing his Saturday night as I was starting my Sunday morning. On Saturday nights, Daniel would club his way up and down 13th Street, migrating from ICandy to Letage, or Dirty Frank’s, or the U Bar, or sometimes to a house party for drinks. When Saturday night was fully spent, he’d make a last stop at the Black & Brew for some eggs before stumbling up his apartment steps next door to sleep through the morning hours.

The first few Sundays that Daniel and I spent occupying neighboring tables, we each kept our faces buried in what was in front of us—breakfast and sermon notes in my case, and whatever copy of the New Yorker, Vinyl, or VICE magazine the Black & Brew had left out for customers to peruse in his. But one Sunday, I had a vague sense of his gaze wandering again and again to settle on my turned back, Bible, and shuffle of papers. After finishing his breakfast, he emptied his cup and plate into the dish bin near the door, opened it to step out into the chilly morning air, and turned to me as he left, inquiring: “Is that, like, a Bible or something?”

I told him it was, introduced myself, and asked his name.

“Daniel.” Then, after a short silence: “Are you some kind of priest or pastor?”

I nodded, admitted I was, and divulged that I was looking over my notes for our worship service that day.

“Wow. Really?! . . . Well, see you next Sunday, I guess, Father.”

He breezed out the door. I listened to the thump of Daniel’s ascent up the steps on the other side of the wall to his second-floor apartment to end his Saturday night. I felt sure I had scared him off—that next weekend he’d surely find somewhere else to enjoy his eggs and coffee in peace, somewhere that wouldn’t put him in such dangerous proximity to a Christian minister.

But I was wrong. When I walked into the Black & Brew the next Sunday morning, there he was: same seat at the bar, same eggs Benedict, hollandaise spilling over the side of the plate, same flat cap. We exchanged a knowing nod as I sat down, placed my order, and arranged the contents of my bag at my usual table. To my surprise, after a few minutes, I saw a shadow across my right shoulder and turned to discover Daniel standing at the edge of the table. “So, what are you talking about this Sunday, Father?”

I don’t remember the text I was preaching on or the topic of the sermon for that Sunday, but I do remember staring at Daniel, then staring down at my notes, then staring back at him again, and having not the slightest idea what to say. Eventually, I fumbled around, attempting to relate whatever selection from Exodus or Isaiah or John we would attend to that day. We talked for a few moments, and then Daniel left as usual, thump-thumping up the stairs next door.

This bit of sermon discussion happened this way, at that back table, most Sundays over the next few years: several sips of an Americano, a few bites of breakfast, and then, “Hey Father, what are you talking about today?” It was the best preaching class in which I’ve ever enrolled. I’d taken courses to learn the Scriptures, courses to enable me to preach and teach them in the context of a church community, and courses to sharpen and hone my communication skills. But I had zero idea how to translate the gospel proclamations of these ancient texts for someone like Daniel—someone who knew almost nothing of the Christian story, whose cultural vocabulary didn’t include the insider speak of my faith, and whose life and family experiences only sporadically included entering a church building. Those conversations with Daniel forced me to wrestle with questions I had never seriously considered about Jesus, the Bible, and God; they compelled me to relearn the language of faith in a way that would be meaningful and jargon-free to someone like Daniel; and they ultimately helped me find my voice in conversing about life, death, and Father, Son, and Spirit to my many friends like Daniel who live their lives outside the decaying ruins of Christendom. Week by week, to this day, as I sit in my study with piles of books, that same Bible perched on a lectern, and scribbles of notes and ideas, prepping for the weekly work of preaching and teaching, I picture Daniel easing into the chair across from me to ask that same question: “What are you talking about today, Father?”

Think of what follows here as an extension of those conversations Daniel and I had, Sunday by Sunday as we sat in the Black & Brew. I’d love to include you in them. And I hope you’ll pull up a chair and bring with you your questions and puzzles about faith, your cynicism and pain, and your flickering inklings of desire or hope or joy.

4 Responses

That’s a very compelling story.

Thanks for this, Jared. I’m not a pastor, but I suspect that if someone were to ask me a question similar to Daniel’s, namely “What’s Christianity all about anyway?” I would have the same difficulty you had initially. In fact, I remember now talking with one of my Redeemer University students after class who said she’d lost her Christian faith and focused now on just living a good life, and that that would be enough. I remember trying frantically to remember what C.S. Lewis said about that in his book Mere Christianity. I remember being rather dissatisfied afterward at my not being more helpful to this student.

Thanks for this. I like your comment that the disciples would have initially dismissed the Easter message of the women as “fake news.” I noted that leros was used only in that Luke passage in the NT, and also found it once in the Septuagint in 4 Maccabees 5:11 when a pagan disparages the “philosophy” of the Jews as nonsense. I was wondering where you learned about its cruder connotations as BS. I like it when translations don’t try to clean up biblical language, but go with a cruder original meaning. It appears you feel the same that I do on this. As for part two of your article, it would be good for all pastors to think how they would phrase their message for someone who knows nothing of Jesus.

Your relationship with Daniel reminded me of the Ash Wednesday I stopped at the grocery store following our service (complete with the imposition of ashes in the shape of a cross).

A man stopped me in the juice aisle and asked what they “meant”…he had seen several people that day and had finally decided to ask someone.

How do you distill an answer (which for me would probably be too long-winded) into something which just might have some meaning for the asker.

This was a great post! Thank you for sharing.