Mom is standing at the white double sink with drain board in a Leave it to Beaver kitchen. I want a drink, and I’m looking up at her, unable to see the bloody meat she’s working with, cracking it apart so it will thaw faster and she’ll be able to get supper on the table at a reasonable hour.

“Be patient, Grampa Hank!” she hollers down at me. “You’re just like old Gramps—you’ve gotta have it right now, dontcha!”

I stomp my foot. I do want a drink, I’m thirsty, but she’s just turned this moment—the simple need of a child dying of thirst—into a double bind: choose death or align myself with my wicked hypocritical grandfather.

Grampa Hank, I know at the earliest of ages, is the name of the man whose dry, still house we go to Sunday after church, where the conversation is oppressed by long silences and Dad looks like he’s being interrogated for crimes he didn’t commit and Grampa hollers from his chair at Grandma for this and that.

“Mary! Get me a cookie!”

“Mary! Bring me that bulletin once!”

“Mary! Open the curtains!”

Not done quickly or to his satisfaction, he begins to raise himself against his immobility, cursing in Dutch under his breath.

Now, this man, Mom is saying, is me.

Even as I weigh the dilemma, being like Grampa or dying of thirst, my heart beating in my chest at the prospect, she’s washed her hands and gotten the water. “Here—here’s your water. Impatient, just like Old Gramps! That’s what I’m going to call you—Gramps!”

After that moment, whenever I got impatient with her, Mom indeed called me Gramps and that insult began its drip-dripping on the rock that was my nature.

Dad’s strategy was different. He turned to fishing.

Those were the Jimmy Carter seventies. With prices down and interest up, the banks said to borrow-borrow-borrow because everything would come back. So Dad did. He put up a freestall barn, future site of his state-of-the-art milking parlor. Then he bought a new, modern tractor, a closed-cab John Deere 4440. He and I took pictures on it one Sunday in church clothes, me standing high on its hood, he holding me so that the roaring south wind wouldn’t blow me off, one picture with formal smiles, one with Dad cringing, as if he were thinking, “Dear God, what am I doing?” The dairy was brimming and the farm buildings were flush with life and we were tractor-tire-deep in debt.

And I was king of all I surveyed. Mornings, I’d wake up and farm the green shag carpet of the living room with a full array of toy John Deere implements, make a hundred bank shots on the basketball hoop nailed to the garage, hit whiffle balls into the lawn and maybe pet the cats. Half an hour later, I’d nag mom, “I’m bored—what can I do?” Rinse, repeat. It drove her batty.

And so, I got a special invitation to the fishing party. For Christmas one year, I unwrapped an orange and white Snoopy fishing pole complete with plastic plug to practice casting. Casting that plug into the lawn and fantasizing about reeling in crappies and walleyes got added to the morning repertoire.

A half hour later, back to nagging.

As the nagging increased and Carter stretched into Reagan, Dad hatched a plan to take me fishing, just him and me.

“He’ll never have the patience for it—he’s got too much Hank in him,” Mom told Dad in confidence, so that I could hear perfectly. The idea that I might somehow have Grampa Hank in me got my attention. It terrified me.

When we left the yard for the first time in our always-dirty Scottsdale pickup, ten-year-old Heidi forgotten somewhere in the house, I could feel Mom’s doubt: “Good luck! We’ll see how long he lasts!” I steeled myself against it.

Dad insured his wager with a safety net: he promised we’d always catch something; he bought snacks to eat while we waited; he promised (an unspoken promise) that if I would be a good fisherman (patient and not a complainer) I could spend hours away from home with him, just him and me.

Lake Shetek itself added to the magic. The rock-lined road with water on both sides was like the path of the Israelites through the Red Sea. We parked on the islands and walked back out to sit on the rocks and bobber-fished away the afternoon.

I memorialized that first trip in my earliest elementary school writing: we went to Lake Shetek; while it rained, we had our lunch of chocolate milk and powdered donuts; we caught a perch and a crappie.

*

Bobber fishing—Dad always called it a dobber—is good discipline, biceps curls for your patience. Dad set up my Snoopy pole with a dobber, split-shot weight, and a gold hook. We always used a fixed pencil bobber with a fire-red tip, yellow shoulders, and white underbelly, swelled out in the middle like a pencil had swallowed a marshmallow.

My job was to watch this thing. So on the puzzle-pieced rocks on the south side of the second dike on Lake Shetek, in the dry, still afternoons, I watched it.

As it slid almost imperceptibly up and down the bank. As it bob-bob-bobbed on the waves of a southeast wind. As it sent out almost imperceptible blips on the water.

“Dad, I’ve got a bite.”

“That might just be your minnow. You’ve got a lively one on.”

As I waited, hands braided to my Snoopy Pole, I was the paragon of patience. Or obsession-compulsion. I didn’t throw rocks or wander up the bank or ask to go home. For hours and hours I sat, baited by the promise.

And prophesy. “It’s only four o’clock sun time,” Dad would say. “In another couple hours the walleyes will start coming in to shore.”

That prospect redoubled my determination to watch. And pray.

“Please, please, please let me catch a fish, please,” was easily my earliest and most earnest prayer. Still is.

Then I made up rhymes. “Wall-eyes, wall-eyes come to shore, so my life won’t be a bore.”

I watched and prayed, chanted and incanted through the long afternoon. Mostly, my dobber prayers met silence. But I just kept asking. When it bobbed in with the waves, I casted again. And again and again and again.

I got false positives: when what looked like a bite was actually a snag. I endured suffering: when my reel wouldn’t cast and Dad undid the front cover only to find a rat’s nest of tangles inside, and it seemed like I’d never cast again. I met despair: when the thought arose that we were fishing in an empty puddle and the cars going by on the road were all laughing at us, that there were no fish and there was no God.

No, against this, I simply had to believe.

And endure. I endured through the long afternoons—because He wants this. So I determined to be the longest endurer.

Because with endurance did come answers. The down periscope bite, a submarine slowly submerging. The bob and weave bite, slight bounces this way, then that. The staccato bite of sharper ups and downs. And most unnerving of all, the dead man’s float, when a bobber comes up instead of going down, a prayer sent back to you so you might reconsider.

“That’s a crappie bite,” Dad would prophesy, “get ready—tighten your line.”

And just like that it would dive, as if to the abyss itself, as if God had just been teasing you, God, the creator of the teeming fishes of the deep.

“OK now, set the hook!”

And I’d reel in a madly flapping crappie with a plastic, dainty mouth. Dad would poke the stringer up through the slot on its gill, toss it in the water, and there it was, my own fish that I could always check on—check on as proof. There was a God.

*

Maybe half a dozen trips into Dad’s wager, we got skunked for the first time, and that meant everything was being tested.

Like Dad’s benevolence. “Sorry, Pal,” Dad said. “We’ve never got skunked before, have we? I usually get you to catch a fish, don’t I?”

“It’s not your fault, Dad,” I said but didn’t mean. I was trying my best not to pout, which is to say I was ready to go all blubbery-fist-pounding tantrum. I could almost accept his offering, that he was somehow to blame.

“Not even a bullhead!” Dad said, and it was the most frightening line of all. I felt the lack of even that universal devil-fish as great injustice, as if something was working actively against us. Or someone.

As if it were predestined.

Skunked.

That word and how I felt about it dredges up the whole apparatus of how I thought the world worked then.

On the one hand, there was Grampa’s God.

Every Sunday at Leota Ebenezer and afterward in my grandparents’ living room, even if the conversation was about the weather, commodity prices, who got a new car, the air was dense with theological principles: providence, depravity, election. It was a confined and confining world, where everything happened by the hand of God and the only real option was nose-to-the-grindstone diligence.

The God of Grampa’s living room was dour—though, to be fair, the light that poured in through the picture window—that illuminated the whole scene—had a name, “grace.” You just didn’t know exactly what to do with that grace. It never quite translated into unrestrained joy for Grampa, and certainly never into any kind of bacchanal: at Grampa’s birthday, when we gave him a bottle of Mogen David or King Solomon wine, he closed the curtains before he partook. Then, in a surprising move, he poured everyone a small glass, even us kids.

When confronted with this God on Lake Shetek, earnest prayer became a way to somehow move him to action, convince him you were worthy. He was out there, this otherwise-preoccupied Father was—hadn’t he done enough already?—and you were asking him, impossibly, to just take a little more time and tie a fish on your line. So you endured to prove yourself and to move God out of torpor and indifference and convince him to bless you with his hesitant hand.

But there was another God, too. This was the God of the brimful farm, of a spooked herd of bovine trampling through a fence. The one who sometimes overdid things, who multiplied flicker tails in the pasture till they became a plague that dug out rows of newly planted corn, a hole for every regular seed dropped from Dad’s John Deere corn planter. This was the fun God, the wild or even OCD God, the one who was busy tracking every loop de loop of all the iridescent barn swallows, who noted when even one of them was nabbed out of the sky by a tabby.

This was the crazy uncle God, who stashed away coins in the mouths of fish for a rainy-day fund. The God who would let you fish all night without catching and then show up on shore wild-haired and whimsical in the morning and say, “Oh, not catching anything?—here, hold my beer—OK, cast your nets on the other side of the boat—” and the waters would literally swarm with fish, to the point of creeping you out, to the point of terror.

This was Dad’s God. Rollicking and chaotic, joyful and unpredictable, profligate and dangerous.

He was manic.

That manic God was why you endured.

*

But now we were skunked; Grampa’s God was in charge.

And then, miracle.

As we came out of the trees along Valhalla Road to the open water of the first dike, the last piece of hope before the never-ending prairie, we saw three clumps of fishermen standing around the culverts that ran underneath the dike.

“What’s going on here? They must be catching something,” Dad said. We drove slowly past the first two crowds, looking along the water’s edge for stringers in the water, of which there were several, with long clutches of white bellied fish on each.

“Do you want to try it here, Pal?”

Naturally.

The farthest culvert only had one or two fishermen by it. Dad parked at the end of the road and walked back up to the culvert to ask if we might fish there. When he came back, he was excited.

“He’ll let us fish by him—he’s a real nice guy.”

I got placed right on the corrugated metal of the culvert, the prime spot. The water boiled out slowly beneath me, eddying and roiling in a way that was magic in itself. They were biting on black Mister Twisters, of which we had exactly none, but the guy—really a nice guy—gave us a couple.

They were like black licorice with yellow eyes. The lead head gave way to a body that was squishy, vinyly to the feel, tapering down to a fragile tail that flopped in the air and fluttered in the water. Genius. Gorgeous. Dad tied one on the Zebco 33, his rod and reel, and gave it to me.

“Here, I want you to catch one. You can’t use your pole for this. Go ahead, you can do it.”

And I knew I could because of practice on the lawn. I casted and reeled, pulling the Mister Twister through the water, watching its yellow eye and spinning tail the last few feet as it climbed out of the push of the current.

On one of the casts, true to the man’s promise, something grabbed it.

“Dad, I got one!”

Dad, incredulous: “Really?”

“Here, use my dip net,” said the man as the fish fought me across the current.

“Yeah, I forgot to bring ours along,” Dad lied.

Its side came up golden in the late evening water, its large eyes dark and blue.

“Yep, that’s a walleye.” Dad’s voice trembled slightly. I can’t see the second fish in my memory as it came in. It was smaller but still a keeper. Dad, feeling like we had intruded on the man’s territory—that we’d probably already taken advantage of the grace allotted to us—that his prayer had already been answered beyond what he could have asked or imagined—said we should go. When we left, the man and most of the crowd were still fishing. The sun had set.

“How was that? How’s that for getting skunked?!” he said in the pickup as we drove away, playfully slapping me with the back of his hand. “I told you we’d catch something.”

I couldn’t stop smiling.

We stopped at the bait shop, Pete’s Corner, where they weighed the fish, then snapped a Polaroid with us holding them, the weights of each fish written on a chalkboard behind us, something official, like 1 lb. 8 oz. and 3 lbs. 2 oz.

Considering the drought that came after, we should have framed that picture. To help us hold on.

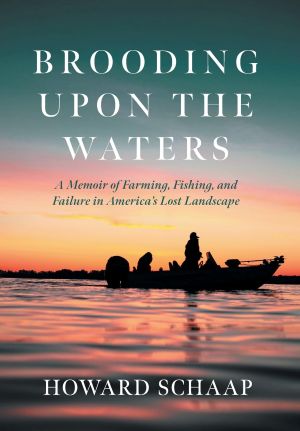

Excerpted with permission from Slant Books from Brooding Upon the Waters, which will be released on December 2, 2025.

*****

Kind readers and good friends, it is the week of the Reformed Journal‘s annual fundraising campaign. We ask for your support. Click on the purple box below to find out all the information and opportunities. Of course, we always draw your attention to our But Wait…There’s More! offer. Three, great new books sent to you in 2026 as a token of appreciation for your support. Click on the purple box for all the details and ways to give.

Thanks so much!

Reformed Journal is funded by our readers; we welcome your support. This holiday season, we call your attention to our “But Wait…There’s More!” deal—three new books sent to you in 2026!

For a gift of $300 or more between now and the end of 2025, or a monthly gift of $25 or more in 2026 and you’ll receive these books. (Canadians: due to shipping costs and exchange rates, we are asking for a gift of $450 (CAD) or $38 monthly.)

Click the purple button above for more details on this year’s special “But Wait, There’s More” offer—three new books by Reformed Journal contributors in 2026! You can use the same page to give an online gift of any amount or to find info on giving by check via mail.

Checks may be mailed to:

PO Box 1282

Holland, MI 49422

One Response

Delightful! I don’t fish but I was rooting for you all the way! Thanks for the smiles.