Airline travel provides opportunities to meet people with stories to tell. Some travelers pray about those who will sit next to them so that they can have an opportunity to share the gospel or to encourage a fellow believer. I, however, pray that the person next to me will have an entertaining tale for me. As Chaucer demonstrated, interesting companions on a journey, especially a religious pilgrimage, can make travel a pleasure.

All That’s Holy is the story of Tom Levinson’s four-month pilgrimage to discover the nature of faith in America. Like the pilgrims in Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales, the characters and their stories in Levinson’s book are delightful and diverse. The result of Levinson’s work is a pleasing collage of companions who reveal the hues and patterns of American faith. Perhaps the most interesting companion is Levinson himself.

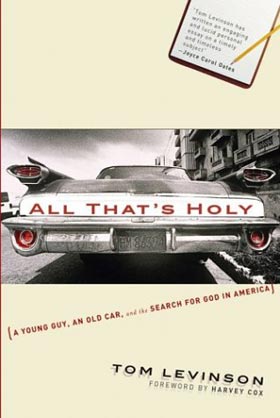

Tom Levinson set out on pilgrimage from Boston in August of 1999 in his “old car,” a 1994 Nissan Altima. He is a fourth-generation Jewish New Yorker, who, like so many in America, grew up uninterested in religion. After his bar mitzvah, he didn’t set foot in a synagogue again until the end of high school.  It was then that he took an elective course on the history of religion and was captivated by the Bhagavad Gita, the Gospel of Luke, and the story of the Buddha’s enlightenment. At Harvard, he became a religion major and, after graduation, determined to set out on this pilgrimage. (He quips that he could have become a tele-rabbi. I think he made a wise choice.) The journey becomes as much his own story of deepening faith as it is the story of faith in America.

It was then that he took an elective course on the history of religion and was captivated by the Bhagavad Gita, the Gospel of Luke, and the story of the Buddha’s enlightenment. At Harvard, he became a religion major and, after graduation, determined to set out on this pilgrimage. (He quips that he could have become a tele-rabbi. I think he made a wise choice.) The journey becomes as much his own story of deepening faith as it is the story of faith in America.

Pilgrimages are usually defined by their destinations–Canterbury, Jerusalem, Mecca. The destination of this pilgrimage was not a place but rather conversations about faith. He printed up business cards that read, “GOD IS: AN ORAL HISTORY OF FAITH IN AMERICA, Tom Levinson . . . Project Director.” It was a Tocquevilleian journey to discover the nature of American faith, what makes religion in America tick; and the journey was accomplished by talking with interesting people.

The traveling companions we meet along the way would have made Chaucer envious: A Branch Davidian in the Waco, Texas compound. A homeless woman practicing the I Ching with a library copy and coins secreted in an Altoids mint container. A fundamentalist Christian at Liberty University. Muslims in Toledo. A Cambodian Buddhist in Boston. The owner and resident theologian of a post-modern worship center and coffee shop, the “Coffee Messiah,” with a sign out front that says “Caffeine Saves.” A Hare Krishna. A Mormon. A “Cafeteria Catholic.” A civil rights activist who describes himself as both a Muslim and an African Methodist with Holiness leanings in a Baptist Church. A 102-year old former pastor of an Apostolic church she planted and pastored for 55 years until she turned 94. A death-row inmate with a convincing conversion story interviewed nine days before his execution, and the inmate’s ordained mother interviewed six weeks after. Though the journey was only four months long, the stories reflect America’s history and diversity.

Levinson’s journey provides insight not only into faith in America, but into Levinson’s own faith. One perceptive insight comes as Levinson recounts an exchange with Mike Holton, another unforgettable character, who is the church administrator of Wedgwood Baptist Church in Fort Worth, Texas, where six weeks earlier a deranged gunman had opened fire in the church, killing seven people before he killed himself. During their conversation, Holton learned that Levinson was a Jew and so proceeded to share the gospel with him.

Levinson acknowledges to Holton that “I certainly consider myself Jewish. But if being saved is about taking Jesus into your heart, trying to know him, trying to have him influence your life, do I also consider myself saved in some respects? Absolutely. . . . And what I’m realizing is that you can be both . . . And it doesn’t make you less of the other.” He then laments that Jews have generally rejected Jesus, one of their own rabbis, who would undoubtedly be in the Jewish Hall of Fame (if there were such a thing). All the Christian pilgrims he met on the journey, he says, can “consider me saved . . . . Except I’m going to make that mean something else, something new, something my own–not to diminish the way you know it, but to expand the way I do. In the process of reshaping and retrofitting Jesus to make him both applicable and appropriate for my life, wasn’t I engaging in a most American form of interpretation” (pp. 239-240)? Indeed, he was, as evidenced not only in Levinson’s story, but also in that of the Coffee Messiah, the Christian-Muslim activist, the Cafeteria Catholic, and so many others. Faith in America is what each person wants to make it.

At the beginning and the end of the book, Levinson draws a connection between his work and the work of Casy, the ex-preacher in John Steinbeck’s classic The Grapes of Wrath. Casy gave up “preachin'” and determined to listen to people, to understand how and why they live the way they do and why they do the things they do. Though he’s a talker, Casy gave up preachin’ because “Preachin’ is tellin’ folks stuff. I’m askin’ ’em. That ain’t preachin’, is it?” He wants to understand the ordinary stuff of life, “All that’s holy, all that’s what I didn’t understan’. All them things is the good things” (quoted on pp. x, 396). As Levinson likewise avoids the “preachin'” and goes about the “askin'”, he does reveal the good things we might otherwise miss, the holy things we might walk right past. Levinson points them out like a good preacher who has done the needed work of listening first.

Throughout Levinson’s pilgrimage, he wandered into fascinating locations and encountered unforgettable people, mostly without any prior planning or preparation. In Seattle, a postponed appointment on a rainy day leads him to the basement dining hall of a Methodist church where he met the homeless I Ching practitioner. Still in Seattle, the need to pull over to find a place to relieve his bladder leads to the discovery of the Coffee Messiah. Some of his stops are planned, many just happen, and some take strange turns.

An attempt to hear the Dalai Lama in New York’s Central Park results in his being on the fringe of the crowd, sitting with a man named Elvis, too far away to hear much of anything that the Dalai Lama said. He reflects on the moment and notes that it must have been a similar scene at many of the great moments of religious teaching: Moses’ farewell speech to Israel, Jesus’ Sermon on the Mount. In reality, he suggests, most people in the crowd couldn’t hear what was being said. When the speaker told the crowd to remember what was said, it was really “a recognition that folks in the bleachers needed some help to know what went down. This struck me then as an important point: most of us don’t find ourselves within earshot of Moses. And in the absence of front row seats and first-rate speaker systems, we need to be in earshot of one another” (p. 31). We need to tell and retell the stories. That’s what Levinson does for the reader. He retells the stories he heard so that those of us in the bleachers, and those of us who can’t take the time for such a pilgrimage, can learn what’s going down. He retells the stories of those who journey in faith with us in America, introducing us to fellow pilgrims. Being in earshot of Levinson isn’t as good as being in earshot of Moses, but it does offer rich treasures–and tales that are as satisfying as Chaucer’s.