Bad joke alert! Brace yourself.

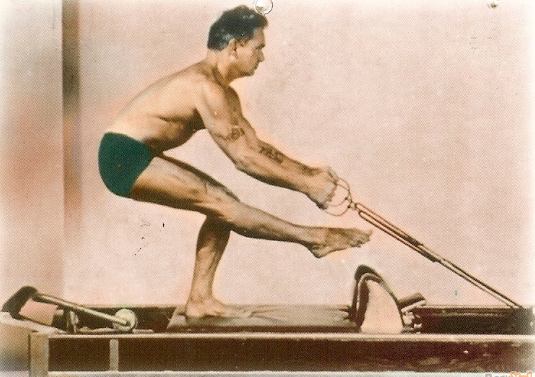

“So,” says the fitness buff to the pastor, “what kind of pilates was this ‘Pontius’ that Jesus suffered under?”

Groan. Sorry.

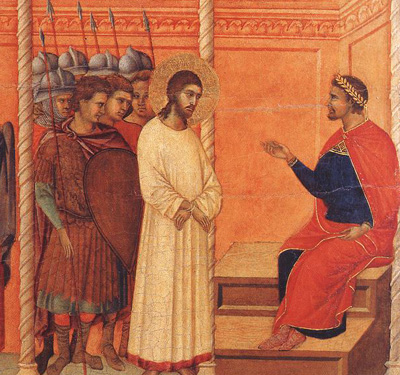

Perhaps it speaks of a world where people have no idea that Pontius Pilate is the name of the Roman Prefect of Judea who presided at Jesus’ trial.

I have never liked Pontius Pilate. Sunday School socialization works. That some Christians venerate Pilate and his wife as saints, based on apocryphal texts? That legend says he died in Switzerland, where, presumably, there was plenty of clean water for frequent hand washing—well, who knew?

I always resented Pilate’s presence in the creeds. He felt like such an inappropriate presence, a festering sliver, an interloper. There, in our brief summary of faith, where Peter and Paul and countless others receive no mention, Pilate intrudes week after week. It’s like the vice-governor of the Idaho territory being included in a brief bio of Lincoln.

Then one day I was reading Karl Barth’s Church Dogmatics. “The inclusion of Pontius Pilate in the creed means, inter alia, that the Church wished to pinpoint the death of Jesus as an event in time” (III.2.441). Barth then notes the insistence on precise times (cock’s crows, third hour, etc.) surrounding Jesus’ death as recorded in the synoptic Gospels. These particular and in-time details distinguish the events of Jesus’ death from the “once-upon-a-time” of classic myths or timeless ideals, such as “after winter, comes the spring” or “from the ashes, the phoenix rises.” Barth may have been poking at Rudolf Bultmann’s de-mythologizing project, but for me it just makes it easier to include Pilate in the creed.

I’ve always liked the suggestion, fanciful as it may be, that we should punctuate that line of the creed differently. Rather than professing, “He suffered under Pontius Pilate, was crucified, died and was buried…” what if we were to profess instead, “born of the virgin Mary, he suffered. Under Pontius Pilate was crucified, died and was buried…” The focus of Christ’s suffering would be shifted from solely under Pilate to his entire life.

It reminds me of Q&A 37 of the Heidelberg Catechism.

What do you understand by the word “suffered”?

That during his whole life on earth, but especially at the end, Christ sustained in body and soul the wrath of God against the sin of the whole human race.

That phrase—“during his whole life on earth”—always catches me. It is a small and surprising treasure. All through his life, Jesus was a man of sorrows and acquainted with suffering.

- Escaping to Egypt, the infant Jesus suffered.

- Hungry, lonely, and tired in the wilderness, thirty-year-old Jesus suffered.

- When his town folk tried to push him off a cliff, Jesus suffered.

- Not thanked by nine of ten healed lepers, Jesus suffered.

- When the rich young man walked away, Jesus suffered.

- In numerous confrontations with the religions authorizes, Jesus suffered.

- When his friend Lazarus died, Jesus suffered.

- Weeping over Jerusalem, Jesus suffered.

This isn’t to say he was the melancholy, miserable Jesus often found in movies. Despondent, eyes glazed over, shuffling through life mumbling mysterious maxims. “Man of sorrows” doesn’t equal “gloomy Gus.” Recall Jesus was also called “gluttonous” and a “winebibber.”

Attending to the whole life of Jesus might seem like a variant on the watered-down “Jesus as moral exemplar” theology, whose life “showed” more than his death and resurrection “did.” But that’s not the case here. The Catechism rightly reminds us that it was “especially at the end” of his life that Jesus suffered, but it also refuses to make an artificial distinction between Jesus’ ministry and his passion. Instead it holds together both “his whole life on earth” and “especially at the end.”

Jesus’ whole life, suffused as it was with suffering, is redemptive. Jesus didn’t spend thirty-three years wasting time and hanging out until he could finally suffer and die. A few years ago in Perspectives, Calvin College religion professor, Thomas Thompson strikingly suggested that today’s typical Christian “embraces too glib a conception of Christ’s atoning sacrifice…Go to the cross; go directly to the cross; do not pass go; do not collect 200 disciples; do not have a life or ministry…With a greater emphasis on Christ’s life as itself a life-of-sacrifice, we can assay his death not so disjunctively—as the isolated moment of salvation—but in better continuity with his life as epitomizing his sacrifice and obedience to God the Father’s will.”

This week we focus on the end of Jesus’ life, events that are at the center of our faith. As I recite the creed, Pilate’s intrusive presence will remind me of the concrete particularity of Jesus’s suffering, during his whole life on earth, but especially at the end.