The neighbors have that iconic Harvey Dunn (“The Prairie is My Garden”) up on their living room wall, bold and beautiful. Somehow, I’d almost forgotten the man, the artist, South Dakota’s pride and joy. So on a little trip out west a week or two ago, we decided to stop at the gallery on the campus of South Dakota State University, and have a look at an exhibition of his work that features his most memorable prairie skies. It was wonderful.

It’s clear that Harvey Dunn loved women. They’re often featured in his work–strong, brave, powerful figures who made life on the Plains work for themselves and their families. Look, she’s the central character in the drama unfolding all around her. Maybe she has no garden yet on the homestead–maybe she does but it’s all potatoes and kale. Whatever her lot, she’s come to understand that the prairie itself is gorgeous, bedecked in all kinds of native color, and she’s not about to nurture her growing family without beauty.

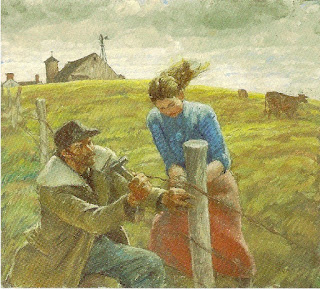

Here’s another–“Fixing Fence.” It’s a team effort, and her husband is himself quite the romantic figure, just as strong and handsome as she is. But she’s the one without the coat, and the one doing the toughest job. Even though she’s remarkably young, Dunn put her at the heart of things here to make it clear to everyone who witnesses the scene that this young lady may be a beauty, but she’s no wallflower.

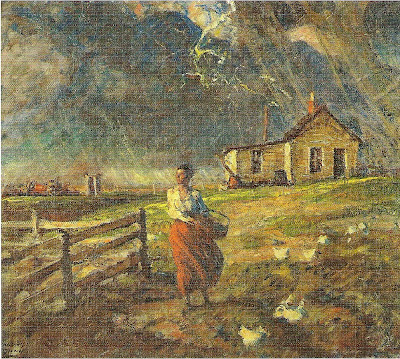

And another, “Just a Few Drops of Rain.” Well, the skies tell a different story. Anyone who’s ever lived out here–where weather almost always comes in spades–knows that a sky like that is nothing to shake a stick at. What’s going on around this woman is not just a few drops of rain, but she’s out there anyway as if it is because she’s not going to be bested by bolts of lightning dancing through a darkened sky, or the gully-washer that’s sure to follow. She has things to do.

You walk through a gallery of Harvey Dunn paintings and you can’t help but remember a story that few tell anymore, the rugged story of homesteading families out on the Plains or at its borders, breaking ground for new communities, new worlds. That story–and let me say this bluntly–is, almost entirely, an Anglo story, a white story, a European-American saga that’s not so much despised as simply forgotten.

Often, with good reason.

When my great-great-grandparents came to Wisconsin in the 1840s, they displaced Kickapoo and Sac and Winnebagos, the very Winnebagos who now live out here on the emerald edge of the Plains. The Winnebagos are here, 500 miles west, because of my own great-great grandparents, who came, who built, and who conquered.

Derrick Hartman and his family, just off the boat, bought forty acres of unimproved land near what was then Milwaukee and proceeded to settle in. But life wasn’t easy, and the skies above their heads threatened as startlingly as do the skies above the woman on Dunn’s prairie. Horror fell in great bolts: Derrick Hartman lost in quick succession his wife, three sons and a daughter to some plague of illness. I would love to know how a pious farmer like himself reckoned his fate with the hand of the God he worshiped.

Then this, from a biography of Edgar Hartman, his remaining son, in a Sheboygan County history:

With his father and the remainder of the family, our subject came to this county in 1846. They were compelled to take their axes and cut roads land, paying $1.25 per acre. This property was in the midst of the forest and had never before been occupied by white settlers. Then the hardships and trials of the early pioneer were experienced, for they had very little to eat, not much clothing, and scarcely any of the comforts of life. The red men were still numerous in this section, but were not troublesome to the white settlers, except as beggars. The first home of the Hartman family was a rude log cabin, with puncheon floor, and the chimney was a simple stovepipe thrust through the clapboard roof.

My own family came and built and, for better and for worse, conquered. I’m here because sometime early in the 1840s, Derrick Hartman decided, somewhere in Holland, that his family could have a better life if they’d leave the old country and strike out for a new one in what was for them a whole new world.

That story–the story behind the Harvey Dunn’s famous work–is my story, for better (it’s massively heroic) or worse (we displaced a people, decimated a culture). In America, it’s the white man’s story, a story–as a Navajo friend of mine likes to say–of massive illegal immigration.

All of that I couldn’t help but see in the paintings of Harvey Dunn.

Last week my neighbor took me out along the Floyd to show me where a gang of beavers had built a dam to make a swimming pool, a haven for their underground homes, places only they could reach in the higher waters. It’s an amazing construction, really, worth seeing like few sights in the county, I think.

But he also told me that right there, at a big bend in the Floyd River, the Yankton Sioux, who once roamed the grasslands all around, used to like to camp. Made sense–you could see for miles right there where the river makes a hairpin turn. An old man told him he used to find artifacts right there above the bend, lots of them.

Which got me to thinking that maybe, just maybe, some old 19th century beavers engineered a dam back then too, created something of a lake right there on the Floyd, a place where you could pull fish from the water, a place you could swim, even in a drought. The Yankton Sioux may well have found a beaver dam a great place to camp.

And they’re still there, those beavers, even if the land is a checkerboard of yellowing beans and corn these days and the Yankton Sioux are a hundred miles west into South Dakota, the grassland gone forever.

For those beavers, I suppose, little has changed. They have their story too.

Something about that makes me smile.