Editor’s Note: We invited Jon Witt, professor of sociology at Central College, to share research he’s done on the connection between the rise of the Religious Right and the rise of people who identify as “religious Nones.” Jon’s insights will be in this space not only this week, but the coming two Mondays as well.

Part One

Part of the reason I became a sociologist was to better understand religious trends in the modern world. I’m not sure there’s a better time for sociologists of religion than right now. There’s so much going on. The research that’s being produced is fascinating and abundant. I’ve had a terrible time keeping up with it while writing this piece because some new data or analysis comes out almost every day. Two trends are particularly striking. The first is the rise of the Nones. The second is the interface between religion and politics. The quest to understand both, and the possible interface between them, sent me down many rabbit holes. Here I provide a guide to a few of them and some thoughts on finding some pathways out.

While conservative Christians are circling the wagons calling for a commitment to core values and practices that map well to key Republican priorities, politically moderate and liberal Christians are rushing to find the exits. The result is a growing divide between more ideologically pure conservative Christian communities on one side and a more secular, more liberal group on the other, many of whom do not identify with any religious tradition. Having explored these trends, sociologists and other scholars have concluded that the politicization of American Christianity on the Right played a substantial role in the rise of the Nones.

The Rise of the Nones

The rise of the Nones is now well known, especially in religious circles, and much research has been done on them over the past twenty-or-so years. Still, I thought it might be helpful to begin with a brief overview. Who are the Nones? They are those who, when asked about their religious affiliation, say some version of “None of the above.” They are typically divided into three categories: Atheists, Agnostics, and “Nothing in particular.” Individuals in this third category, sometimes referred to as “unchurched believers,” often believe in God or some other higher power or supernatural realm. What most distinguishes them is their lack of participation in, or affiliation with, an organized religious community.

According to Gregory Smith at Pew Research Center, the Nones make up 29 percent of the adult population in the United States. The following graph tracks their rise over time, including trends for each of the three categories of Nones. The percentage of Atheists and Agnostics rose from a combined total of 4 percent in 2007 to 9 percent in 2021 while the size of the Nothing-in-Particular third group grew substantially from 12 percent to 20 percent.

Source: Pew Research Center – Smith 2021

Results from other national surveys, collated by political scientist Ryan Burge, place the percentage of Nones in the United States in a range from 23 to 36 percent (see also Burge’s article & tweet). Regardless of which wording or methodology used, all studies show that the Nones comprise a substantial portion of the population and that their numbers have risen significantly over time.

Speaking of Burge, when it comes to data necessary for understanding Nones, I would be remiss not to highlight the importance of his work. Burge is the go-to guru for data on, and analysis of, the Nones. His book, The Nones: Where They Came From, Who They Are, and Where They Are Going, now in its 2nd edition, provides a comprehensive overview of the field. In addition to regular academic and popular press articles, Burge regularly posts intriguing data snapshots on his Twitter (X) account (@ryanburge) and explores provocative hypotheses on his Substack account (“Graphs about Religion”). For anyone interested in the Nones, Ryan Burge is a must follow.

To better understand the rise of the Nones, it is helpful to consider how identifying as a None can vary for different categories of people. Taking age into account, for example, helps us to better understand variation in their rise and provides a window into the future of American religion. Younger generations are substantially more likely to opt for Nonehood, though all generations show an increased likelihood of identifying as Nones over time.

Source: Burge based on CES Data (See also Burge)

Almost half (48%) of all members of Gen Z, those born since 1996, identify as Nones, and Millennials (44%), born from 1977-1995, aren’t far behind. Compounding matters, the Silent Generation (18%), born from 1925-1945, with its high level of religious adherence, is rapidly being replaced by Gen Z (see also projections and analysis from Pew Research Center). These trends should be enough to make any religious leader quake in their boots. Some may seek comfort in the notion that those Gen Z’ers will come back to religion when they are a bit older and have kids, but there’s growing evidence that this may no longer be a safe assumption (see Margolis 2017, 2022).

Digging a bit deeper into those three categories of Nones, Burge reports that 31 percent of Gen Z identifies with that Nothing-in-Particular third category, a substantially larger number than those in their generation who identify as either Protestant (20%) or Catholic (15%). They are also twice as likely than the overall population to self-identify as Agnostic (9%) or Atheist (9%). Jewish, Muslim, Mormon, Orthodox, Buddhist, and Hindu groups each come in at 3 percent or less.

As an important aside, one of the more interesting outcomes of the research from Burge and others is the fact that there is a positive correlation between religious identification and education: People with more education are more likely to be religious. People with less education are more likely to identify as Nones. Among those whose highest level of education is a high school degree, 30 percent are Nones compared to 25 percent for college graduates and 21 percent for those with a Master’s degree (see also Burge). The same trend regarding education holds true for religious attendance. When it comes to income, there are significant differences between the three catogries of Nones: Atheists and Agnostics have higher incomes and Nothing in Particulars are much less likely to have high incomes. Another possibly counter-intuitive trend in current data is that, young women are more likely to identify as Nones than young men.

Nones have to come from somewhere. The inverse of the rise of the Nones has been the decline of other religious groups, and the group that has suffered the greatest loss is Mainline Protestants. My favorite graph related to the Nones shows these trends over time starting from 1972 when the General Social Survey (GSS) first began collecting these data.

Source: Burge

Two trendlines in this graph are particularly striking. The first involves those Mainline Protestants. This graph makes the pattern clear. There’s a precipitous drop from approximately 30 percent of the US population in the early 1970s to roughly 12 percent today. Some Mainline groups are bleeding members. The Presbyterian Church (USA), for example, lost 51,584 members in 2021 alone and dissolved 104 congregations. The following graph from Burge demonstrates that they are not alone among mainline Protestant denominations.

Source: Burge

A significant factor in such declines is the failure to retain members across generations. In the 1970s, according to Burge, 74 percent of those raised in Mainline churches remained there as adults and 6 percent became Nones. In the 2010s, 55 percent raised in Mainline churches stayed and 19 percent became Nones.

The degree to which conservative Christian churches also face declines is up for debate. Burge argues they are not declining but also says your interpretation of the data serves as something of a Rorschach test. Indeed, a lot does depend on how you look at the data: according to that 1972-2018 graph above, it looks to me like there was a peak in 1993. If you track the numbers from then, or even if you started from 1985, it looks like Evangelicalism is in decline. If you start tracking the number earlier, as Burge urges, the percentage is relatively flat over time. Another data source, PRRI’s 2020 Census of American Religion, reports that the percent of White Evangelical Protestants has fallen steadily from 23 precent in 2006 to 14.5 percent in 2020.

One of the factors complicating data from conservative Christian denominations is the substantial rise of nondenominational churches, some of which may be products of denominational splits. For example, Southern Baptist Church membership peaked in 2016 at 16.3 million but is now down to 13.2 million. Over the past three years, they have lost more than 400,000 each year, the equivalent of losing more than all of the RCA and CRCNA combined each year, all before its disaffiliation with Saddleback Church and its 20,000-or-so members. At the same time, non-denominational churches are up significantly.

The second striking trendline in that 1972-2018 graph provides an earlier starting point for the rise of the Nones and uses a different dataset. Initially, we can see the relative constancy of those who identify with “No religion,” hovering between 7 and 8 percent, from the early 1970s to the early 1990s. At that point, something seems to happen, and a steady and substantial rise goes from about 7 percent in 1991 to about 23 percent in 2018. Burge points out that this 1990s rise in Nones was particularly sharp among young adults. Going back to that 2021 data from Pew, the number of Nones in the United States (29%) now exceeds the number of Evangelicals (24%). According to Burge, about a quarter of Nones were raised as Catholic, 13 percent as Mainline, 10 percent were Evangelicals, and 5 percent were Black Protestants. (Note: The GSS numbers for 2021 were problematic (see Burge), so I am not relying on that dataset for the more recent numbers of Nones.)

This leaves us with the big question: Why? What caused the substantial rise of the Nones? As with all things human, the answer is complicated, and sociologists, along with other researchers, have spent a significant amount of time sussing out possible causal factors in all their complexity. But one thing is clear: the political turn right in White, conservative Christian culture played a significant role.

Mixing Politics and Religion

According to sociology’s Thomas Theorem, what’s perceived as real is real in its consequences. In other words, our perception of the world shapes how we act. As we will see, Nones view religion very differently than do religious adherents. Members of these two groups do not share the same reality.

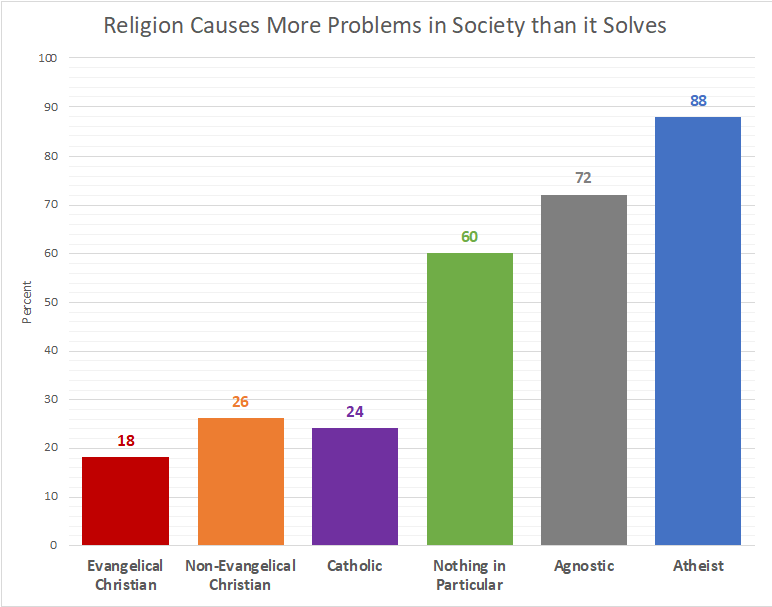

Source: Burge using PRRI data

For Nones, religion is more dysfunctional than functional, and their likelihood of seeing religion this way has increased over time. This may not be a surprising result for Agnostics and Atheists, both of whom are defined to some extent by their opposition, or at least ambivalence, to religion. It is the growth in opposition to religion in this Nothing in Particular category that is particularly curious. As we’ve already seen, most continue to believe, so their opposition seems due, at least in part, to concerns about religion as a public institution.

Sociologists and others have noted that the rise of the Nones correlates well with the rise in prominence of the Religious Right as a political force. Critical historical milestones include:

- The founding of the Christian Coalition in 1987 by Pat Robertson and led by Ralph Reed starting in 1989;

- Pat Buchanan’s “Culture War” speech at the Republican National Convention in 1992 during which he proclaims, “There is a religious war going on in this country. It is a cultural war…for the soul of America”;

- Bill Clinton’s election later that year, which energized many conservative Christians who questioned both his personal and public morality throughout his presidency;

- The establishment under the Clinton administration in 1993 of the “Don’t ask; Don’t tell” policy which relaxed legal restrictions regarding sexuality and military service;

- Newt Gingrich’s rise to prominence in 1994 (see The Revolution podcast hosted by Steve Kornacki) along with Gingrich’s Contract with America;

- The corresponding Republican takeover of the House of Representatives for the first time since 1952 as a consequence of their 54-seat swing and the corresponding Republican takeover of control of the Senate;

- The passage of the Defense of Marriage Act (DOMA) in 1996 which defined marriage as “a legal union between one man and one woman as husband and wife” and banned federal recognition of same-sex marriages;

- The Clinton scandal involving Monica Lewinsky which gave rise to the Starr Report which led to Bill Clinton’s impeachment in 1998.

According to these researchers, the increased politicization of religion is driving people away from the church. Data consistently show an increasing association between conservative Christianity and Republican politics and a corresponding link between the rise of the Nones and Democratic or Independent political identification.

A corollary to the Thomas Theorem is that a person’s position shapes their perception. When it comes to religion, knowing a person’s religious affiliation makes it possible to better predict their political affiliation.

Source: Burge

In those pre-1990 days before the rise of the Nones, there wasn’t a significant difference between Republicans and Democrats when it came to religious adherence. In their in-depth study of U.S religiosity, American Grace: How Religion Divides and Unites Us, political scientists Robert Putnam and David Campbell summarize that period this way: “…a half century ago, political ideology and religiosity were essentially uncorrelated in America, with lots of liberals in church pews and many unchurched conservatives” (p. 143). As Ryan Burge put it, “If someone walked into an average Protestant or Catholic church in the 1980s, they were just as likely to sit next to a Democrat as a Republican. That’s no longer the case: In almost all majority-white Protestant churches, political conservatives dramatically outnumber those who are left of center.”

Times have changed. Over time, a “God Gap” opened up between the political parties. Religious people are more likely to vote Republican and non-religious people are more likely to vote for Democrats. Black Protestants are the most conspicuous exception to this rule.

White Evangelicals have become significantly more politically conservative. In 2012, 18 percent of White Evangelicals self-identified as Very Conservative; in 2021, this self-identification rose to 33 percent. In 1972, weekly church-going White Christians were more likely to identify as Democrats (55%) than Republican (34%). By 2021, these numbers had completely flipped. Now, 62 percent of weekly church attending White Christians identify as Republican compared to 21 percent as Democrats.

Nones, on the other hand, are much more likely to identify as politically liberal (44%) or slightly liberal (33%) than slightly conservative (18%) or conservative (12%). In a study that followed the same people over time, among those who identified as Christian in 2011, Democrats (13%) were twice as likely to switch their identification to None than Republicans (6%) in 2020.