“The Reformation achieved great popular success because it satisfied, or promised to satisfy, the needs of many people who earnestly desired the consolations of the Christian religion…. they were sincere seekers after salvation who looked to the church for succor, and, not finding it there, turned against the traditional religion and its representatives with all the anger of disillusioned love.” (Williston Walker, The History of the Christian Church, Fourth Edition, p. 421)

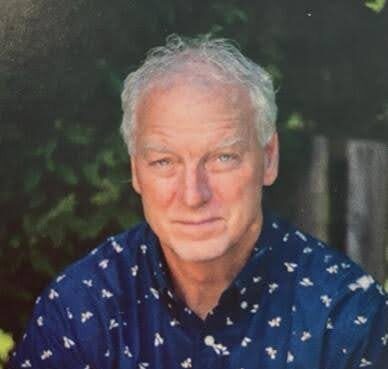

I first read these words 37 years ago during my ministerial studies at Calvin Seminary. They reinforced a belief that every once in a historical while, spiritually dead and misguided religion must reckon with the human soul’s unquenchable desire for peace with God. We are again in such a time of reckoning. As the world is collapsing around us, sincere souls are seeking succor from the church and are not finding it. I am one of the disillusioned and angry ones.

I decided to leave ordained ministry in the Christian Reformed Church over the course of two-and-a-half years, in three overlapping stages. First, I left my congregation to protest religious Trumpism, and, following that, found myself in a spiritual wilderness. Second, I fell into the arms of chaplaincy training, during which a Muslim family, a Hindu man, and an atheist banker helped me find Jesus again. Third, I studied the United Church of Christ, and was captivated by three spiritual concepts—including a story about barnacles—which have helped me find peace and spiritual direction.

If Donald Trump revealed the heart of white evangelicalism, he also altered the brain-chemistry of the Christian Reformed Church. It was like after Edmund, in The Lion, the Witch, and The Wardrobe, had eaten Turkish Delight. Mr. Beaver could tell from the look in Edmund’s eyes that he had been with the Queen/White Witch, eaten her food, and was no longer on the side of the fauns and the animals. Mr. Beaver said to the other children, “The moment I set eyes on that brother of yours, I said to myself, ‘Treacherous.’”

During Trump’s presidency, the evangelical church began to show his dangerous look, disregarding Trump’s racism and turning a blind eye to his moral degradation, misogyny, and shaming of immigrants. Under the sway of Trump’s leadership, hostility and aggression from the Religious Right became commonplace, even in the CRC. Church councils intimidated, manipulated, and persecuted good and decent pastors who dared venture the most careful and reasonable critiques of Trumpism. A church secretary read the emails and letters addressed to a pastor friend who had attempted a gentle word of biblical critique and implored him, “Please—you should step down and leave. I am afraid for your safety.” Elders of CRC churches sent threatening letters to denominational staff. Donald Trump awakened something deeply wrong in the soul of the CRC. Others, trying to be nice, trying to hold their churches together, trying not to poke the bear, or just trying to keep the budget solvent, tolerated or sought to appease the Trump-factions of their congregations.

The humble denomination of my upbringing was gone. In the past, my people suffered loss, if need be, for the quiet good of God. No doubt, we were stubborn. Yet, we freely confessed that we had sin in us and among us. We lived in fear and trembling before God. We believed, as Reformed people, in considering matters carefully and with biblical discernment. Now, retired pastors with respected names in the CRC are suffering depression from the state of the denomination they spent their lives nurturing. All those sermons, all those Bible studies…just for this rotten fruit? Active pastors knew their sanctuary platforms were powder kegs, and their congregational leaders were coming to church each Sunday with their tithes in one pocket and matches in the other. What could pastors do but sit on their hands and duct tape their mouths?

It is my unshakeable conviction that religious Trumpism is idolatry, openly racist, and a poisoning of the simple gospel of Jesus. Since there was a strong Trump-supporting base within my congregation at the time, there was no way to speak about or confront this large-scale toxicity in the broader church without hurting the congregation I was pastoring. Despite meaningful relationships with many loving and well-intentioned congregants, I initiated an amicable divorce following the rules of the CRC.

The bottom dropped out of my faith in “organized Christianity.” There was no truth for me in the church any longer. (This song by Dan Deitrich expresses how I felt https://youtu.be/WidUnxxovD8.) I didn’t know where Jesus was, but I was pretty dang sure where he wasn’t. Bereft, I went into the desert wilderness, and there beheld the bleached bones of my former beliefs, practices, and identity. I can tell you: Disillusionment sucks.

At the same time, I embarked on a two-year training process for chaplaincy. I worked on a suicide unit at a mental health hospital, and then for a year as a resident chaplain in a Tier-1 trauma hospital. From within the wilderness, I began to see signs of divine beauty in the depths of human suffering.

I remember weeping with a Muslim family at the bedside of their deceased loved one, with as deep a sense of fellowship as I had, over so many years, with my most beloved church members. Another time, I was present with a Hindu family during the death-process of their elderly mother. After she died, I escorted the family to the hospital exit, and there, in the dim and empty hallway of the early morning, suddenly one of her sons turned and hugged me, full-on, and we held each other. I believed, in that moment, Jesus was there, between us. Admittedly, this did not happen in every meeting with every person. Some days of chaplaincy were just normal workdays, and sometimes my heart remained unmoved. Yet at frequent and startling moments, as I met with all sorts of people, I regularly saw flickering images of Jesus in them.

These people were sent to me while I was still in the desert, and it was as if God showed me a little stream, or had uncorked within me an overflowing fountain. I found myself lavishly distributing Jesus in ways that were outside the limits of my church teachings and practices. I splashed water for baptisms in ways that stretched and broke my previous definitions. I rummaged around in staff break rooms for crackers and sugary grape juice, offering these bargain-basement elements as holy sacraments to people with only the slightest impulse of faith. I helped organize spiritual rituals for people of completely other faiths. I flung God’s love around like the wild sower in Jesus’ parable, trusting that God would grow things anywhere God wanted. I saw that so many of these people were like seeds trampled underfoot already, stripped and beaten by hell. It anguished my heart to see, especially, that many of my suicidal patients had been abandoned, cast out, and rejected by harsh, authoritarian, and law-based religions of all sorts. In those moments it came down to this: here, the water. Here, the saltine cracker, and the grape juice: the gifts of God for the people of God—for any humble, suffering, desirous soul. Oil and wine for their wounds. My hands, my heart, promptly offered up, and touching the flesh of humanity.

On the suicide unit, and in the hospital, I encountered people from many expressions of Christianity. I observed that the hyper-religious, loud-mouthed people who proclaimed themselves to have mighty faith, patriotic morals, and essential truth actually possessed only distortions and twisted imitations of Christianity; on a few occasions their faith manifested as something resembling mental illness. In vivid contrast, the simple, pure, rugged presence of Jesus was evident in the weakest and humblest human beings.

Increasingly, then, all the profound and precious gifts my family and forebears gave me in my upbringing and training were no match for Jesus, revealing himself this way. All that I had believed for a lifetime and preached across three decades of ordained ministry could not keep up with what Jesus was teaching me on that suicide unit, and in that war-zone of a hospital. It must sound grandiose, but I did wonder if this was what the Apostle Paul described: how all of his life’s efforts, all of his fire-breathing religious exertions, had been overtaken and swept away by the sheer, simple, sweet, surpassing greatness of Jesus. This, in my own small way, is how it felt for me. I was both crushed and liberated.

I used to think, as a Christian, that I had something unbelievers didn’t. Especially as a pastor, I had some eternal truth people needed to hear, something I needed to press upon them. Serving as a chaplain, the spiritual house of my construction crumpled like wet cardboard. I began to see Jesus was already within other people—in fact, flowing from them to me. I was cut to the heart with the realization that, largely, in my earlier life and ministry, I had been missing Jesus. Passing him by.

In a hospital room one day, I met a retired banker who welcomed me but told me upfront that he had given up on God long ago. I listened for a long time as he shared the very real and painful reasons for his blend of agnosticism and atheism. I presented no argument. Silence surrounded us for a few moments, and then I ventured to tell him my heart: “Yeah, I get it. I feel those things, too. It’s just—I just can’t help it—it seems to me like I experience God right now, just with you and me, right here.” It was quiet again, and then somehow we went on and talked about other things. Eventually, I had to leave, but right before I crossed the threshold of his door, he said, “Hey Chaplain…just so you know, about ten minutes ago, I started believing in God again.”

After oh-so-many moments like that, with so many vibrantly diverse people, it struck me with undeniable force that God does not abhor our fallen, human condition, but is already present within people’s souls, and is, just as Jesus described, already, and always, working. This was true long before I showed up with my evaluation of the person’s spiritual condition or my pulpit-words to say.

I had stumbled from the wardrobe and there was the lamppost. This was divine joy, and it saved my lost and fallen soul.

Meanwhile, the CRC was taking a jaggedly different attitude, with Machiavellian vigor and punitive intent. By approving the Human Sexuality Report and locking it in as confessional, and by initiating attempts at church discipline for those who believed differently, it elected to play Religious Whack-A-Mole with a Bible-mallet. The mindset which had overtaken the Christian Reformed Church was thoroughly contrary to the flow of my heart.

In our human misery, suffering, and searching, Jesus is our friend. He demonstrated this with his open, safe, non-violent, and protective presence. He travels “the highways and by-ways,” and welcomes wild humanity to his feast, without distinction. His feast, his people. Rhapsodize all you want about belonging, but if the “unworthy” people I am meeting every day, who are friends of Jesus, are barred from your table, then I would rather go over to their house, and ask if they would allow me at their table.

Williston Walker follows the chapter on the spiritual awakening of the Reformation with “Separations and Divisions.” This includes accounts of the Reformers drowning people they considered doctrinally impure. Leaders in the current CRC speak of “cleansing the church,” too. Though I am still Reformed (the Heidelberg Catechism is one of the founding testimonies of the UCC), I decided to oblige their desire for cleansing and transitioned away from the CRC. The United Church of Christ met me on the road.

You can’t just get a quick ticket to ride in the UCC. It requires a year of discernment. I took a class, studied, and wrote papers. Three spiritual concepts stood out in the discerning process, and irresistibly beckoned my soul. I hope these three related concepts may be as uplifting for you as they are for me:

First this, from Daniel L. Johnson and Charles Hambrick-Stowe: “While some denominations establish their identity by inspecting the walls for breaches and requiring those persons inside to conform to essential standards, the United Church of Christ characteristically has held the gates open wide and cultivated diversity.” The authors continue: “To recognize this posture as characteristic is to see that love for those who differ, desire to learn by dialogue, and tolerance of ambiguity are important parts of our identity in Christ.” And then: “This is by no means an excuse for doctrinal laziness. Indeed, the work of theology becomes more challenging as we hold lovingly to our own history and faith expressions while in fellowship with those who, inspired by the same Bible, express the faith differently in their lives and with words other than ours.” (Daniel L. Johnson and Charles Hambrick-Stowe, Theology and Identity, pages xi, xii, italics mine).

Reading this, I was smitten. I wanted to think in this expansive way about the body of Christ. In contrast, the “inspect the walls for breaches and require conformity” approach seemed small and pathetic. I no longer wanted anything to do with it.

Second, from the same book, an illustration about barnacles from Sharon H. Ringe captivated me. She describes how believers like her (a feminist theologian), or from other people groups, may be welcomed into the church as “add-ons.” She writes, “As with barnacles on a ship, there is usually room for one more.” The “welcoming” seems so nice, but becomes problematic when it is only “apparent openness,” and when these add-ons are not allowed to “affect the core structure of the vessel or its course.” Ringe calls this “overt hospitality” with “minimal influence.” (Theology and Identity, p. 119).

Ringe’s barnacle story helped me imagine how female pastors in the CRC may feel. The barnacle story also made me think hard about how I have welcomed people. I’ve known a lot of people, but only a few have made it into the main cabin of me. The same people have always stood with me at the helm and have had all the influence—people who look like me and think like me (or, sadly, I have always thought like them). Same demographic, same governance, same “important people,” same clique. “Outreach” was for barnacles.

As I see it now, there is only one captain of my soul. He doesn’t just superficially accept or tolerate barnacles. He takes everyone in, and doesn’t put up with preferential treatment, entitlement, or power games. He has his benevolent eye on a communion of saints, a vast gathering. This means I need to be open, curious, and adventurous. God’s people are as numerous as the stars in the heavens. It’s high time I navigate my journey by them and with them.

Third, I witnessed a panel discussion with three UCC pastors: an older white male from the conservative/traditional wing of the denomination; an African American male; and a Queer woman who is married to another woman. The discussion was wide-ranging, but at one point the white conservative pastor said: “I want to make clear that all three of us love each other in Christ. We are in a weekly Bible study together. We pray together. We deeply disagree on our views, and we are deep friends in Christ.” The other two panelists warmly affirmed his words.

It took me a moment to realize that my eyes were stinging and I had forgotten to breathe. I felt like I was standing on the edge of the Grand Canyon—the “book stuff” from the UCC study materials was actually being lived out and expressed, with color and majesty, right in front of me. To be clear, there are Trump voters in the UCC. Not every congregation is Open and Affirming. But they can talk and discuss and disagree without anyone trying to kick anyone else out. And they stand decisively for human dignity and justice. “Well now,” I thought, after the panel discussion, “look at that! The love of Christ is actually possible for believers who live and think differently.” I haven’t gotten over it.

I am 62 years old. When my kids were babies, I tried to get them to eat lima bean paste from a glass jar, using a plastic spoon like a crowbar against their pursed and spitting lips. Is this how God has felt all these years while coaxing me to open my heart to humanity? I only have a short while, now, to learn, and to function differently.

I refuse, anymore, to spit at God. I refuse to see anyone as a barnacle. I long for everyone to be fully and joyfully on deck and 100% in the conversation about our destination. I find this vision and attitude exemplified in the particular UCC church I attend. The Spirit has given new skin to my bones and has breathed fresh life into my soul. It is my re-formation.

There are many in the CRC—pastors, elders, deacons, and congregants—including dear friends and mentors of mine—who are giving their best intellectual and spiritual gifts to help the CRC find a more Jesus-like way. They have valiantly stayed, and are risking their jobs to resist Religious Trumpism and to promote a more beautiful Gospel. With all my heart, I admire and love them. We have taken different paths, yet our tie still binds.

It is always about the Spirit, “binding in covenant faithful believers of all ages, tongues, and races.” (UCC Statement of Faith, the Moss translation). Christ calls us into peace with God, unencumbered by earthly agendas and liberated from human judgments and bullying. If your soul yearns for that, by all means go after it with all your might. It may be that you are called to stay and carry this light and this vision in your current congregation—and if so, go for it with joyful abandon and bright confidence. Or, it may be that you are called to a transition to a new journey—a re-formation in your own soul, spirit, and practice: Jesus, unlimited.

My pastor expresses this in our church every Sunday morning: “No matter who you are, how you identify, who you love, or where you are on life’s journey: know that you are welcome here, and that you are loved by God.”

Every Sunday, this sounds like Jesus to me. In this spiritual attitude, I have found peace in my soul and the freedom to live it. So may it be for you.