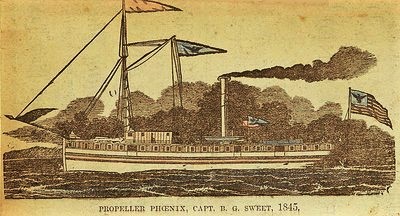

What do we know about her? She was just a kid really, no more than two years old, but she was cutting edge, a propeller-driven steamer built for the Great Lakes in Buffalo, NY, where thousands of European immigrants would be waiting to be transported out to the frontier of the American Midwest, all of them strangers in a strange land. Aboard was as much cargo as she could hold–coffee, molasses, and hardware, not to mention people, hundreds of them.

It was November of 1847, so when the Phoenix left Buffalo, bound for Wisconsin, the crew might well have been celebrative–after all, it was late in the year, and the owners had made clear this trip would be the last before old man winter would make things treacherous, Lake Michigan winter storminess not to be toyed with.

By weight alone, most of the cargo was Dutch–as many as 250 immigrants climbed on board for the last leg of their trip to a new home in a new country, to Sheboygan County, Wisconsin, the place the leaders had decided upon, a land whose woodlands meant days and days of hard work if the soft and sandy soil were to be cleared for crops. They wanted to farm. Like all immigrant people, what they really wanted was a new chance.

Most, if not all, were “separatists,” members of a religious sect some called “the Afscheiding,” the rebel church, arch-conservatives who’d departed the state church of the Netherlands not that long before and whose persecution therefore by civil authorities opened their ears and hearts to the possibilities of immigration to a new land where they could be free. They were an American trope.

Historians claim Lake Erie was calm when they left Buffalo on November 11, the weather not at all as menacing as it might have been. But it turned nasty quickly. People took refuge where they could on board as the swells rose like the shoulders of giants and made everything on board roll. When they came through the straits at Mackinaw, Lake Michigan was no more fair a host, the storms went unabated

Then, slowly southward, the Phoenix moved along into calmer waters and entered the port at Manitowoc, just thirty miles from the dreams of so many aboard. Some cargo was put ashore, but when the captain noted the wind’s return, he kept his ship in the harbor until the lake calmed. The crew went ashore. Some claimed they returned drunk.

At one a.m., the lake calm, the night awash with stars, the Phoenix left for the last leg of a trip I’m sure some had believed would never end, on their way to Sheboygan harbor. Maybe it was haste that lit the fire; some believed it was shoddy negligence fueled by drink. Whatever the cause, those boilers overheated and lit the timbers above them. Soon the Phoenix steamer ship went up in flames.

Soon enough, passengers late that night, November 21, 1847, were awakened to two choices: the flames behind them or the water beneath. Both meant death. As many as 250 died, many–most–of them Hollanders. But then, who was counting, really?–after all, they were only immigrants.

When I was a boy, a highway sign along old 141, the Sauk Trail, told the story. My parents didn’t know much about it, never mentioned it as I remember. Mom’s people were here before it happened; Grandpa Schaap and his family didn’t arrive until ninety years after.

It was the highway sign that put the story into me, not only the tragic and horrifying death out there on the water, on the lake that was a playground when I was a boy; but it was also a story about “tribe” because somehow as a kid I understood–no one taught me as much–that those who died were by some force of nature my own people.

It was a quiet night, I guess. When the ship went up in flames, Sheboygan residents gathered on the beach because the fire was all-too-horribly visible. When the few lifeboats came to shore (only forty survived), I couldn’t help but think that the people there on the beach had to have heard the screams.

I did–so much so that the very first story I ever wrote was about the Phoenix, about God’s presence in darkness and other mystifying questions, about suffering and death, about life and hope.

Somehow, here in the vale of tears, I had in mind that this stark chapter of human sadness was part of a story, an immigrant story I carry, as so many of us do.

Gibbsville, WI