Her syncopated sobs are periodically punctuated with words. “Why?” and “I just want to understand” and “Tell me why.” My seven-year-old granddaughter Amanda’s questions are directed at her daddy, our son Zack. The two of them are on the futon in my writing room. The futon that has become Zack’s bed.

My husband Dan and I are at the dining room table playing a game called “Banana Blast” with our four-year-old granddaughter, Beth. A plastic monkey sitting in the middle of a bunch of plastic bananas launches into the air whenever the wrong banana is pulled from the bunch. The object is to catch the monkey. Bethy loves this game. Dan and I laugh at her laughter. Around the edges of our noise, I hear Zack’s murmured, “I know. I know.”

Zack does not tell his daughter to calm down. He lets Mandy’s distress take up the space it needs. He does not pretend to have answers to her questions, having no answers she would understand—none that would lessen her pain.

Months ago, my daughter-in-law, Lori, and I took a long walk through a nature area roughly equidistant from our two houses. Zack had told Lori about his affair two weeks earlier, saying he considered their marriage over. Ten days after that, he invited himself to dinner to break the news to Dan and me.

Lori said she loves Zack, wanted him to reconsider. I told her more about the history of my own marriage than I ever had. The affair I had long before I had children. The painful aftermath. A bad time, relatively short in a marriage now in its fourth decade, the same story I told my son the night he came to talk with Dan and me. I hoped Zack and Lori would see that an affair does not have to end a marriage. They each agreed to try joint counselling.

But my son refused to treat his romance as a symptom. He will not give up the friend who’s become a lover. After four sessions, he and Lori scrapped joint counselling and started seeing separate therapists. Shortly after that, Zack asked to use our guestroom. He can’t afford to make the mortgage payments on the house the girls call home and pay rent elsewhere.

What answer could we give Zack but “Yes”? “Home is the place where, when you have to go there, they have to take you in.” The best-known line from one of Robert Frost least cheerful poems.

***

After that walk I took with Lori, she sent me a message: “I truly hate that this event is what has led to our spending one-on-one time together.” I winced, not because I thought she intended to blame, but because I blamed myself. Our relationship had been mediated by my being a mother to my son. It had been peripheral to my being a grandmother to their daughters. I regretted not having initiated a more direct connection with her.

Up until the marriage ruptured, I noticed the contrasts between Lori and me. My daughter-in-law is practical; I am cerebral. She is graceful; I am not. But she and I are both introverts, both cautious, both planners. Now, I suspect that these similarities are what my son is fleeing. But who will keep track of the car keys and household expenses if Zack shares his life with someone as whimsical as himself?

***

I start cooking for three but never know from night to night when Zack will join us. He often comes through the front door after Dan and I have already eaten, still talking to a work colleague through his Bluetooth. Too often I wake in the night sensing he’s not in the house and have a hard time getting back to sleep. How could Dan and I be back to housing an adolescent?

I find a damp towel lying on the floor of the bathroom where Zack showers after he’s left for work. I hang it on the towel bar. The third time this happens, I bring it up.

“Hey, could you hang up your wet towel?”

“Do you have, like, a bathmat?” he asks.

The towel on the floor is the one he steps out of the tub onto. It doesn’t occur to him to pick it up, since he’ll just put it down again the next day. I go online and order a bathmat.

Zack offers to cook two nights a week. He gives us a heads up more often when he’s not coming home.

I see that Zack is in agony over the pain his choices cause—will go on causing. I hate that my son is suffering. I hate that my son is causing suffering. I see he’s trying to be as truthful and as gentle as he can be in the strange and disorienting situation that he has gotten himself into. I am moved when he struggles to restrain his tears as he talks to us. Yet agony’s no absolution.

Be brave, I want to say, Life will not always be so painful. Instead, I say, “It’s not your job to make your father and me happy.”

***

I have no idea how to be a decent soon-to-be-former-mother-in-law. My local library has no self-help books on the topic. I find no such books on Amazon. But I discover that “mother-in-law” is not even a legal term. In family law, blood is primary. “Consanguinity” is the legal term. Its contrasting term is “affinity relation.” Affinity is a friendly-sounding word for a flimsy bond. Nothing I can do will prevent me from becoming a former-mother-in-law.

The legal term “affinity” seems unintentionally ironic. In popular culture, parents-in-law are assumed to have disaffinity with their children-in-law. For women, in-law-hood is particularly fraught. Googling “mother-in-law jokes” yields over thirty-three million hits. Many of these jokes are meant to be told by men about their wives’ mothers, but a tee shirt designed for women to wear on Halloween says, “If you think I’m a witch, you should see my mother-in-law.” Such assumptions have spread beyond human relations to the world of houseplants. The mother-in-law tongue plant gets its name from its sword-like leaves. Ingesting mother-in-law tongue leads to gastrointestinal upset and cell death. Pet owners beware.

I begin receiving popup ads and spam from places offering to buy my wedding ring. A side effect of online research in family law.

***

In popular culture, grandparents have robust affinity with their grandchildren, though in legal terms they have consanguinity. On this topic, I side with pop culture.

My young granddaughters show me rocks, acorns, sticks, bugs. They say “pickle” and “pomegranate” for the pleasure of the sounds, the simple joy of repetition. They think I can fix anything with glue or my sewing kit.

One day when Zack has the girls at our house, Mandy asks for a large piece of cardboard. First, she traces her own hand, then she asks me to put my hand down and runs a marker of a different color around it. Next, she coaxes Bethy over, followed by her daddy. Finally, she traces my husband’s hand. In the middle of the handprints, she writes “My Family.”

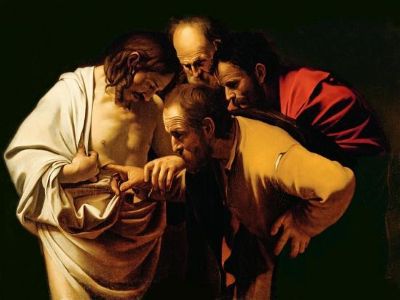

I wonder whether Mandy will make another of these drawings tomorrow at her house—one that would include her mommy’s hand and the hands of her other two grandparents, who have come to town to celebrate Lori’s birthday. Along with Mandy’s own hand, and her sister’s, that would again make five. “My Family” could be written in the center of those hands as well. Family used to feel like a smug sphere. Now I picture a Venn diagram, my granddaughters in the overlap of two circles. The overlap gapes like the wound in Caravaggio’s The Incredulity of Saint Thomas—like the mouth of a cave. I want to crawl in next to them.

Zack had the girls over to my house to wrap birthday presents for their mom. Yesterday afternoon Dan and I went over for a few minutes to drop off the present that we had gotten Lori. The gifts from Mandy and Bethy were set out on the ledge of the fireplace hearth waiting to be opened the next day—Lori’s birthday. We deliberately went over the day before instead of on the day itself. Although we get along well with Lori, every time we walk into her house, which is legally still their house, I can feel that our presence accentuates Zack’s absence, carrying with it all the things we will not say about it.

Before they return home, Lori’s parents will take her to consult a divorce attorney. She doesn’t want a divorce. She hates her current situation. She knows what she doesn’t want. What she doesn’t know is what to do. Our affinity, more than a legal fiction, is rooted in mutual aversion to the only futures on offer.

Many days that last sentence feels true. True and toxic.

***

I want a self-help book on meeting the woman who your son intends to be your next daughter-in-law. I cannot find one.

Instead, I read an essay in Harper’s magazine written by a woman looking back on an affair. I find it illuminating. She says that having “fallen in love” can put you in a hole that is invisible to others. Those around you keep yelling that you should just walk away, not realizing that you cannot walk away, because you are stuck in the hole.

I wonder whether this is Zack’s situation. He needs to keep explaining to people that what he is doing is reasonable because the alternative would be to admit that he is stuck in a hole.

***

Our church stages a sort of Montessori Ash Wednesday opportunity, in addition to the evening service. At whatever time between 9 a.m. and 5 p.m. people want to come, they can use the stations set up in the fellowship hall for individual meditation. One table is set up with a small Zen Garden sandbox, stylus, and miniature rake. The instructions state Write something you want to let go of. Pray. Rake the sand before moving to the next station.

I write Worry. I pray. Recalling verses in Philippians, I ask God to help me give up my anxiety. My prayer stumbles over Paul’s phrase “with thanksgiving.” I rake out Worry, pick up the stylus and write Bitterness. I let the word sit there for a long time before picking up the rake.

***

“It’s hard not to like her,” Dan says after the first time he meets Zack’s new love—Ann. The four of us had arranged to meet at the same nature area where Lori and I had met to walk shortly after I found out about Zack’s affair. The walk allowed for shifting conversational pairings and rationed eye-contact as we made our way through the woods.

“Are you trying not to like her?” I ask Dan.

“Well, no,” he says, “It’s just….” He doesn’t know how to continue. I let the subject drop.

Ann and I had met one-on-one twice before we met as a foursome. The first time for a long walk along a river. “Tell me what you want me to know about yourself” was my opening query. Our conversation meandered from her two boys—a four-year-old and a toddler—to her job, to where Dan and I had met, to how her parents were reacting. The second time we met at a wine bar.

During that second meeting Ann tells me, “People ask me, ‘Who’s to say that this won’t happen again?’” She means an affair, though I’m not sure whose recidivism her questioner intends: Zack’s or hers or both.

“You are,” I tell her. “You are the one to say, ‘This won’t happen again.’”

This mirrors what I told Zack. “The only thing that could make this worse is for all the pain to be pointless. Know yourself. Guard yourself. Make sure you and Ann get marriage counseling at the first sign of trouble.”

***

I have two homes. That was first on the list of three interesting things about her that Mandy put on her poster when she was her class’s Super Student of the Week. This was less than two years after those nights Mandy spent sobbing in our guestroom. The other two items on Mandy’s list were I can do the splits and I know how to knit.

Mandy shares one of her homes with a sister and a mom and a dog named Gracie. Gracie is the rescue puppy, a mutt, who replaced 14-year-old Kramer, the dog my granddaughters had never not known, the dog that stayed with Lori after the split. Kramer died sometime between her parents’ separation and her daddy’s wedding. Before the separation, I had thought that Kramer’s death would be my granddaughter’s most vivid early sorrow.

In their other home, Mandy and Bethy share a daddy and a stepmother and two stepbrothers and a dog named Max. Max, a Labrador pup, was a surprise under the tree the first Christmas the kids all lived together part of the time. One time I asked Bethy whether she preferred being at her dad’s house more when the boys were at their dad’s house, so that she and Mandy could have their dad and Ann to themselves. She said that she liked it better when the boys were there. “Things are crazy when the boys are there,” she said. “It’s a fun crazy.”

One of Mandy’s favorite things about being at her dad’s house is singing to her three-year-old stepbrother as he settles in before falling asleep. Mandy still sees a therapist. Though her daddy thinks she passed the need for one, her mommy disagrees.

In my own house, I’ve packed away the pictures we had in our hallway wall of Zack and Lori together. Now a wedding photo of Zack and Ann and their four children hangs beside one of Lori and her girls—Mandy and Bethy featured in both. There’s also a photo of Dan and I with the four kids staged on a piece of climbing equipment at a local park. Everyone looks happy, but the dappled light requires a close look to be able to make all six of us out.

Dan and I dog-sit for both families, occasionally at the same time. It’s crazy but it’s a medicinal crazy—balmy, as in Gilead’s balm—though our own dog, Lady, resents sharing us with Gracie and Max.

My Venn diagram of our family has gotten more complicated, its overlap more crowded. I no longer see that overlap as a gaping wound. It’s become a yurt in the shared expanse of a sprawling family compound—a gathering space for varied combinations of people over time.

Some of my Venn diagram’s circles seem drawn with faintly dotted lines. At our older step-grandson’s soccer game, I watched his three-year-old brother walk over and strike up a conversation with an older couple sitting some distance down the sideline from us. “He’s made some friends,” I say to Ann. “His Oma and Popa,” she says, “My ex’s parents.” Noting the seating arrangements, I understood that we would not be introduced.

Another day, Dan and I were walking along the sidewalk at a street fair and suddenly one of our step-grandsons was standing in front of us smiling. As we exchanged hellos and hugs, I looked around for Zack and Ann but instead saw a darkhaired man watching. Ah, the ex, I thought. We looked one another in the eye. I suspected he knew who I was. Without acknowledging me, the man said to his son, “Come on, we need to catch up with your brother.” After nodding vaguely, Dan and I moved down the street in the opposite direction from where they headed.

Dan and I hope to continue gracious relations with Lori. Part of graciousness is attunement to the tenderness of scars. “Former daughter-in-law” sounds unfeeling, as does “mother of our granddaughters.” “Friend” feels inadequate for a woman who is not just kith, but kin. Why, here where all extant words wound, has no one come up with an apt neologism?

14 Responses

Oh man. Your mother-in-law is far more gracious than I could be with Zach. His injustice to Lori, despite his hole, would be too much to me. To have him in my house would feel complicit, enabling. So, the story convicts me. It doesn’t convince me, but it convicts me. Would I rake the sand?

Oh man. Your mother-in-law is far more gracious than I could be with Zach. His injustice to Lori, despite his hole, would be too much to me. To have him in my house would feel

Thank you. I take convicting without convincing as a compliment to the story. Caravaggio’s painting convicts me. “Oh man, I’m glad I wasn’t there,” is an honest reaction to Caravaggio’s portrayal of Thomas and his onlookers. The painting asks the viewer “What would you have done?” and “What do you make of what Christ’s doing?” No easy answers are offered.

Wow!!! What a heart-felt and helpful post! Perhaps Luke 14:26 can bring some comfort – it’s about putting the love of God ahead of family love. I’m 77 years old and am coming to see the value of friendship in the healing of wounds. I hope that the adult players in this story will do what’s best for all the children involved by modeling Jesus’ Great Commandment that we love each other.

What a stomach churning piece, with exceptional written artistry: a voice sitting here, exquisite pacing and perfectly timed shifts in sentence structure and arrival of impact. And I need to take a breath or twenty. Thank you . THANK YOU!

So human. So Beautiful. Thank you.

I’m with Jack on this one and need a breath after all that honesty, love, and ache. It made me think of Kintsugi pottery, and how, over time and with an artist’s care, a new kind of beauty can emerge for each part of the broken whole. I sure hope everyone involved in your story may one day, some day however distant, find that to be true.

Thank you, Caroline, for being so vulnerable in offering us this powerful story, in which you are the artist.

Mark, your comment opens an aspect of the story that I had not seen. Mandy is the character in the story we see drawing and singing. We hear that she’s proud to know how to knit. I like that an instinct for Kintsugi might be an unnamed affinity that Mandy and the narrator share.

Having gone through something quite similar, Judy and I thank you for your reflections. They will help us sort though feelings fraught and complex.

Thank you for this narrative of grace and truth – along with much pain.

It is wonderful to see a side of your writing that I’ve never seen before, Carol. It was such a poignant piece, but yet paradoxically so fun, perhaps because our interactions were always work-related, problem-based, and analytic. Thanks for showing us your creative skill.

Wow! What a stunning piece of writing! Yet more impressive is your ability to identify and hold all of that tension in such a loving, compassionate and hopeful way. It’s in the honesty that real healing can take place.

Limerence is such a force, especially when it makes everyday love–the paying of bills, the keeping of promises, the husbond-ry to hushold and children, the observance of communal boundary lines–seem like an oppressive obstacle to being in love.

It is so so so hard to really recognize and compassionately validate our most vulnerable and unruly longings while also affirming that actions of commitment to our vulnerable dependents and partners take precedence. “Feelings are such real things, and they change and change and change.”

Thanks for this story. None of us is immune from situations like this. Limerence is such a pleasurable and treacherous energizer. I love how valuable and alive it can help a body feel, and I hate how it can help a body be willing to trade everything else of value for its high.

I call my former daughter-in-law the daughter-of-my-heart, or my sister-friend. We love each other. Sometimes, she still calls me “Mom.”