The song “Thunderstruck” by AC/DC has been a staple on my workout soundtrack for, well, more than two decades. But now I have a different association with the song, thanks to watching America’s Sweethearts: The Dallas Cowboys Cheerleaders, currently streaming on Netflix. “Thunderstruck” is a signature part of the cheerleaders’ routine and deeply ingrained the organization’s identity.

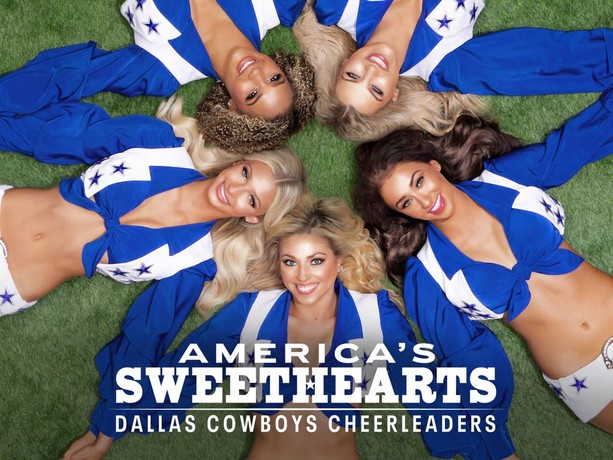

Part documentary and part reality show, America’s Sweethearts features portions of the Dallas Cowboys Cheerleaders (DCC) organization, as well as the tryouts, decisions, and drama about who will make the team for the season. It follows the two women in charge, Senior Director Kelli Finglass, and Judy Trammell, Head Choreographer, as well as a carefully chosen group of veteran cheerleaders and rookies.

As a basic plot line, the series intends to show how great the DCC organization and brand are. The docuseries and the organization are supposedly pushing against a larger cultural narrative of cheerleaders as merely sexualized females who balance the spectacle of masculinity in sports. The show works hard to show how demanding it is to be in the DCC, both from an athletic perspective and from a logistical perspective.

It is incredibly difficult to be selected from among thousands vying for a place on the team. In addition to cheering at games and performing at halftime, the DCC make many appearances for charitable organizations, education, and outreach in the community. According to the official DCC website,

At the heart of the DCC sisterhood is a deep commitment to community service and uplifting others. From visits to schools, hospitals and nursing homes, to hosting youth dance and cheer camps, the DCC are dedicated to making a positive impact beyond the sidelines. Each year, they also perform during the Dallas Cowboys nationally televised Thanksgiving halftime show that kicks of [off] The Salvation Army’s Red Kettle Campaign

In a binder full of instructions (from the 1970s, as one rookie jokes), a mission statement explains a Dallas Cowboys cheerleader:

WHAT AM I … ?

I am a little thing with a big meaning * I help everybody * I unlock doors, open hearts, do away with prejudices—I create friendship and good will * I inspire respect and confidence * Everybody loves me * I bore nobody * I violate no law * I cost nothing * Many have praised me, none have condemned me * I am pleasing to everyone * I am useful every moment of the day

Caitlin Dickerson, writing for The Atlantic, described it as a show about “the cult of femininity” where Kelli and Judy look through thousands of hopeful applicants to find beauty and superior technique, but also a “preternatural quality that makes people want to look at them.”

The two women examine all the hopefuls carefully, speaking in a coded language. Rookies might not be blonde enough, or too blonde. They are too muscular or too big. But instead they speak about being “smart about fueling,” rather than talking about losing weight or dieting. Women hoping to make the team may have lips that are too big or too small, or bodies that are too young or too old. The criticism the viewers see on the show, however, is merely that these candidates don’t have enough energy or stage presence. Or maybe their kicks are not high enough. The DCC is predominately white, but a few women of color feature on the team, and more women of color feature in the second season than the first.

What strikes me is how the show makes visible a singular idea of feminine beauty that is policed, but only quietly, implicitly, acknowledged. The show could highlight the genuine athleticism of the cheerleaders and the wide range of bodies that make up high quality dancers and cheerleaders. And they could emphasize all the less visible work the cheerleaders do in and around the communities.

Instead, there’s a strongly enforced idea of outsized femininity: big makeup, thick long eyelashes, big smile, full thick hair to toss during dancing, a certain type of incredibly thin yet athletic body that is also very flexible, no visible tattoos or unique piercings, and a skimpy 1970s era uniform. The DCC women are always on stage, performing, even when they do charity work and community appearances.

DCC women are paid very little, so they need to have full time jobs to support themselves. That is part of the ethos of this type of femininity as well–low compensation for hard work. In another example of requiring the women to conform to certain feminine beauty standards that are enforced without clear acknowledgement, some of their “compensation” comes from sponsors in the form of hair treatments, botox, fillers, nails, and spray tans. They are told this is a free benefit that they should use and appreciate. As far as I know, they do not receive health insurance, as part time employees. This, even though, many seem to need hip surgery due to the stress and strain of types of high kicks and in the air splits they are required to perform.

Reactions to the show vary, of course. Some critics have called the DCC a cult, while others celebrate the high levels of achievement in professional cheerleading and the bonds of sisterhood that are formed.

It is the DCC phrases “I cost nothing” and “I am pleasing to everyone” that stand out to me as a particularly damaging idea of femininity. I’m stuck on the show’s claim that DCC women have an ethos of “invisible work” (creating friendship, goodwill, justice, respect, goodwill) that is done to be both supportive and kind. Yet the DCC do this invisible work primarily through highly visible, manicured, made-up, tweezed, buffed, highlighted, and streamlined bodies that all fit in a certain kind of uniform in order to do entertaining dance routines for a roaring crowd.

2 Responses

You name a lot of things here, Rebecca, things we often struggle to name. Thank you.

I am also intrigued by this part of the sports enterprise. My son-in-law coaches in the NFL. We attended a home playoff last season and were treated quite royally, including going on the field before the game. The players’ and coaches’ families were escorted to and from the field by the members of the cheerleading squad/dance team. Our guide was an elementary school teacher in the suburbs. I wanted to ask her many questions about her avocation. Last winter I attended a tribute show for the rock duo Heart. The woman who played Nancy Wilson’s role was an outstanding guitar player and singer. She was from Chicago and spent some years on the Bears’ dance team. I think for many women it is a chance to continue to perform, much like community theatre, singing groups, and the like. But NFL dance teams are clearly perceived differently.