Last month, my friend and former pastor, Len Vander Zee, posted a reflection in this space on a “Red State Revival” rally recently held in Grand Rapids. The evening featured Nadia Bolz- Weber, a paragon of progressive Christianity, feisty version, and was held in the local bastion of liberal Protestantism, Fountain Street Church.

For all that, Len marveled, the event did resemble a classic revival meeting: enthusiastic singing, a powerful sermon pointing everyone to Jesus, and personal testimonies—first, from Nadia herself, then from the people in the pews who shared their stories with each other. As a long-time critic of revivalism, yet attuned to the speaker’s political sympathies, I was intrigued by Len’s reflections on what the moment might mean.

WWJD?

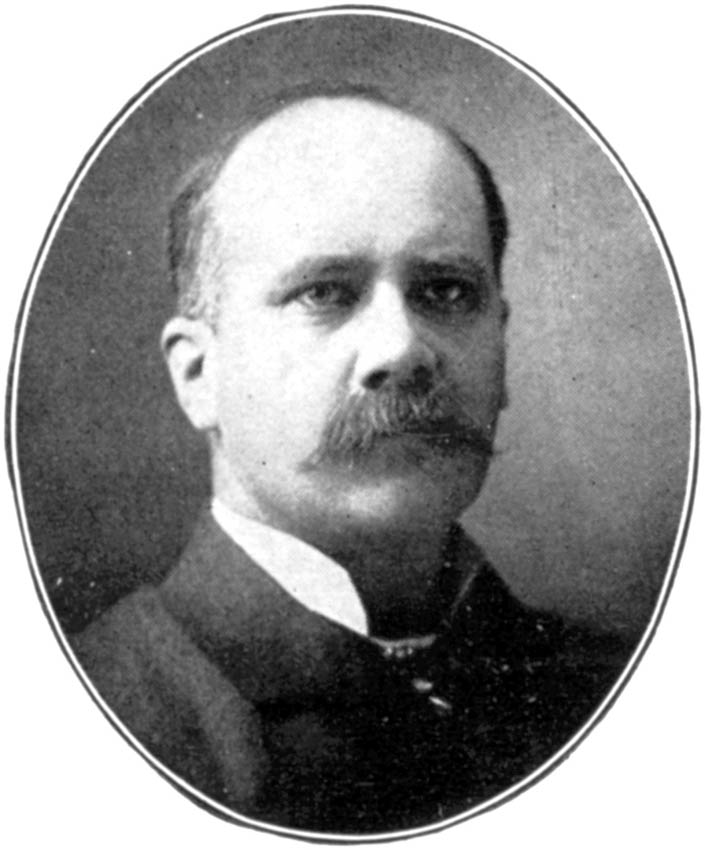

1857-1946

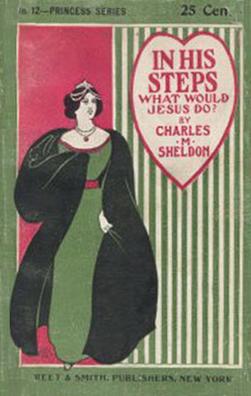

I was also cast back to a book I often taught in my courses on modern American religion: In His Steps, by Charles Sheldon. Published in 1896, a moment of great turmoil in American history, the novel sold 100,000 copies in its first year and tens of millions since, aided by its translation into 21 languages. A hundred years later, a popular movement arose in Holland, Michigan and spread around the globe, bearing the novel’s subtitle on its iconic bracelet: What Would Jesus Do?

The 1990s fad was associated with Evangelicals, but I’m noticing a similar turn to Jesus—especially his example and ethics—on the progressive side today. Tired of theological wrangling and church politics, appalled by heresy hunts and Christian Nationalism, the battered and exiled announce devotion to the person and life of Jesus as their one remaining tether to faith. Their new church is the circle of people who have come to the same place.

That pattern is so similar to the themes of In His Steps that it might be helpful to delve back into that story and review what motivated its characters and what came of it all. It’s a cautionary tale.

Troubling the Comfortable

The story begins at the end of a routine Sunday morning at the First Church of Raymond, Kansas, a railroad town west of Topeka. A homeless man stumbles to the front of the sanctuary and challenges the prosperous congregants over their neglect of the poor and needy. He promptly collapses and is taken under care. On “the third day,” the author tells us, his condition worsens and after a week of suffering, he passes away. He was about 33 years old. Dum-dee-dum-dum!

The pastor and congregation are conscience-stricken and start holding special meetings to discuss the matter. The minister, who had earlier rebuffed the sojourner the better to prepare his Sunday sermon, repents in tears, triggering like emotions around the room. His next sermon issues the WWJD challenge. With that, the action turns from formal worship to the weeknight sessions which for all the world resemble the legendary protracted meetings of Sheldon’s Congregational predecessor, Charles Finney. Here the prim and proper parishioners come to Jesus with intense emotion, group hugs, and, always, lots of tears.

It Works for Some…

That takes us to the end of Chapter 2. The 29 which follow explore how different people in the room try to live out their WWJD pledge. The action is crossed with coincidences, melodrama, and the full range of late Victorian sentimentality and stereotypes. Convenient kin networks and school associations allow the author to eventually shift the scene to Chicago to see how WWJD might fare in the big city. The results in both locales are mixed, and very revealing. Also relevant to those minded to close in on “Jesus alone” today.

The pastor leads off by foregoing his usual vacation and his addiction to careful sermon preparation. From now on he speaks from the heart, at times even slipping into bad grammar. The town’s other oracle is the newspaper editor who decides to ban tobacco and alcohol ads, boxing coverage, and the Sunday edition. In due course he starts an intentional Christian daily courtesy of perhaps the most important figure in the mix, the pious heiress Virginia who funds this and other ventures. Her ne’er-do-well brother, meanwhile, is converted by the singing of gorgeous would-be opera star Rachel who has turned her back on the stage to devote her talents to revivals on Raymond’s skid row. The preppie cleans up, successfully woos the lady, and starts witnessing to his fellow clubmen.

…But Not for Others

The turn is fortunate not only for the rich young ruler but for the city’s flotsam and jetsam who are moved to memories of mother and their better selves by Rachel’s singing. The turn is not so happy for the story’s single greatest washout, the aspiring novelist (Jasper Chase!) who refuses to give up his ambitions. Jesus doesn’t fare well among the high arts. Nor, most ominously in light of the new industrial society that Sheldon means to address, does WWJD make it in corporate America. When the railroad superintendent discovers lies and corruption in the company books, his objections land him out on his ear. He’s reduced to telegraph clerk, his wife and daughter bitterly complaining about their shrunken shopping budgets.

Things are more ambiguous in the sectors of commerce and academia. The department store owner starts treating his staff as family and bans unseemly goods from his shelves but does not challenge the core dynamics of American merchandising. The local college president (Dr. Marsh!) goes through profound agonies of spirit before leaving his ivory tower for the tumult of politics, lending his prestige—but no insights from his social science or psychology departments—to an anti-saloon crusade. WWJD has nothing to say about teaching and scholarship, philosophy and science, just as these took their modernist turn in the 1890s.

Once Again, Symbolic Politics

Instead, the story circles in on the saloon. This is the flashpoint of Christian concern, the key to social reform, the force that drags people down and whose elimination will let them rise again. For all its reputation as a great social-gospel novel, In His Steps practices the traditional mode of Evangelical social ethics, foregrounding one symbolic issue (see also slavery, abortion, LGBTQ, etc., etc.) for Manichaean critique.

While America’s new urban-industrial system haunts these pages, Sheldon offers not a bit of systemic diagnosis or prescription. Notably, it’s the independently wealthy and sole proprietors who can make WWJD work and then mostly in their personal relationships. In His Steps shows contempt for the idle rich and trepidation for the seething masses, and prescribes middle-class goodwill to manage both. It is Rachel’s beauty of face and voice that converts the callow clubman and soothes the savage beast.

“Just Sharing”

Yet the overriding concern of the story turns out to be less the industrial city than the inner world of the zealous, so constricted as they have been by propriety and Victorian repression. Their prayer and share sessions sound not a whit of Bible or theology, nor the slightest word from the heritage of Christian social ethics, but they abound in the gushing heart released from convention and constraint to hug and sob and just feel.

I’m most definitely not saying that Len Vander Zee and Nadia Bolz-Webber fall into this pattern; I know for sure that Len does not. But those fleeing the disappointments of church as it has developed in our time and seeking refuge in the warm circle of Jesus lovers might want to consider the limitations manifested by In His Steps. Pull the Jesus string and eventually you will get the cosmic Christ, the One who is not just (to cite the Anglican communion liturgy) “the author of our salvation” but also, and preeminently, “the firstborn of all creation and the head of the church.” Inescapably, that church exists as a social institution in the presence of principalities and powers.

How it does, and ought to, work there has been the subject of endless conversation over two millennia of history. It’s a subject for us too.

5 Responses

An important cautionary essay. Thank you, Jim.

Thank you, Jim, for this lucid and engaging connection drawn between Sheldon’s In His Steps and “those fleeing the disappointments of church as it has developed in our time and seeking refuge in the warm circle of Jesus lovers.” And yes, that “church exists as a social institution in the presence of principalities and powers.” Jesus’ reiteration of the OT’s command to love God and neighbor has always been – or should be – at the heart of the mission of the church and its members. Its profound implications should keep all of us as Jesus lovers busy.

This is exactly the kind of historical reflection that we need. How was the Holy Spirit working, leading the WWJD crowd to repent of “propriety and Victorian repression“ but not yet repenting of acquiescence to unjust systems? Of what do we repent? I’ve recently become involved with Mennonite Action and come to realize my complacency regarding the suffering of those living in Gaza (Palestine) and my unbiblical desires for military and political action as a solution to injustice. None of us has the whole work of the Cosmic Christ in our hearts and minds, yet we can be sensitive to the Spirit’s leading, as Len Vander Zee and Nadia Bolz-Webber seem to be doing. WWJD is not a bad place to begin, even if it is not enough.

Well, they MEANT to “repent of acquiescence to unjust systems” but didn’t (couldn’t, given their assumptions?) have the capacity to think systemically, and so resorted to personal ethics, caring for individual victims, and symbolic crusading against One Big Evil. I agree: “WWJD is not a bad place to begin, even if it is not enough.” Thanks for your engagement.

Actually, I doubt that WWJD is even a good place to begin. What if it’s a pious distraction, a quick and seemly shortcut that misses the whole country. I don’t see the Apostles in the NT ever evoking anything close to WWJD. I can think of all kinds of things that Jesus did that we shouldn’t, and many things that we should do that Jesus didn’t.