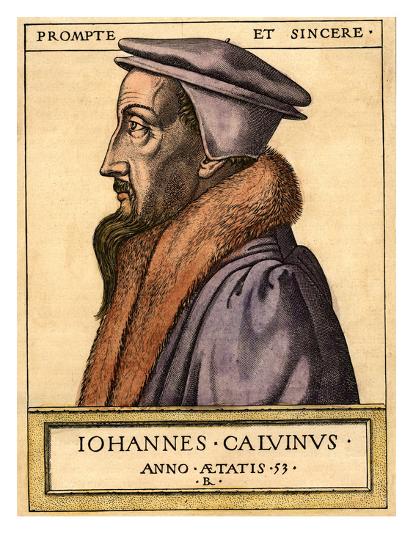

Editor’s Note: this is the first of a four-part series. In this month leading up to Reformation Day, Kyle Dieleman will explore themes in the work of John Calvin — Putting the “Calvin” back in Calvinism.

As a church historian, one of my interests is the way theological ideas and concepts have been articulated differently across time and place.

In particular, all of us who identify with the Reformed tradition find ourselves, by definition, inheritors of a complicated, varied theological tradition. Understanding the roots of that tradition can help us understand ourselves and the place of Reformed Christianity in the world today the same way studying the history of a city or a family can help us better understand our own identities.

The Reformed tradition is certainly not to be equated solely with John Calvin. Nonetheless, his influential theology and ministry is as good a place to start as any when trying to understand the Reformed tradition. Thus, over the next four Tuesdays, I want to explore a few themes of Calvin that I think have resonance for Neo-Calvinist and Reformed communities today.

Before diving in, two caveats. First, Calvin’s theological corpus is so vast and has been studied so thoroughly, that we will have to settle for a relatively surface-level entry into his thinking. To narrow our focus, I will focus mostly on Calvin’ s renowned Institutes even though Calvin’s sermons and biblical commentaries were the bulk of his pastoral work.

Second, outlining Calvin’s ideas and put them in conversation with later Calvinism, I will be intentionally restrained in declaring a who might be right or wrong. I’ll try to point out what I see as opportunities or dangers in Calvin’s ideas, but it is important to know I am not trying to show that Calvin is right and everyone else is wrong. To be sure, there are many things I think Calvin got wrong.

Calvin’s Anthropological Dualisms

Neo-Calvinists, especially the “transformationalist” strands often associated with Abraham Kuyper, have often been suspicious of the dualisms present in theological and philosophical systems. Debra Rienstra’s warning in this blog last week of dualism as a theological weed is just one such recent example. Older strands of scholarship have seen in Christian dualisms little but the corrupting influence of Greek philosophy. More recent trends in theology have recognized that Christian theology, building on scripture, can present dualisms in ways that go beyond a simple parroting of Greek philosophy.

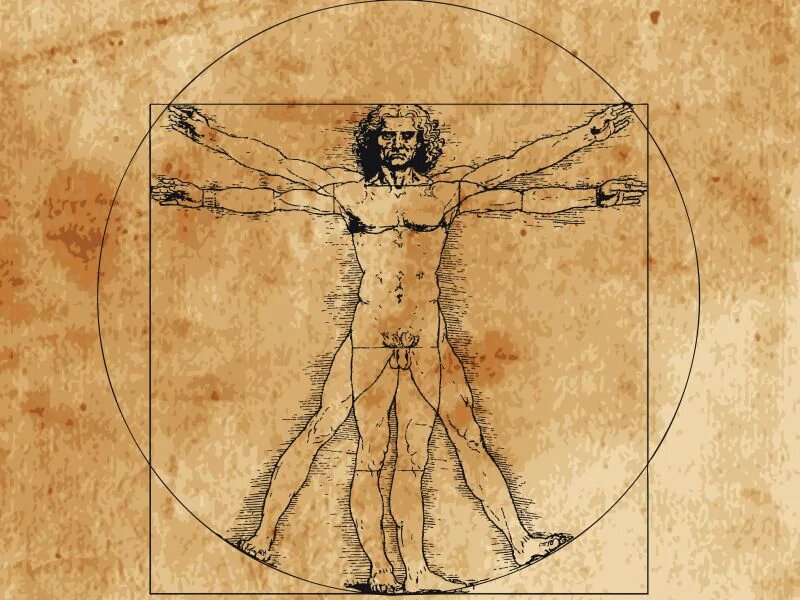

The term “dualism” is almost impossible to pin down and finds its way into theology in a number of areas—creation, grace, culture, and so on. For now, we will focus on theological anthropology. That is, how should Christians think about human nature in relation to God?

Calvin’s view of human beings is undoubtedly dualistic, at least in the sense that he conceives of human beings being created in God’s image with a body and a soul. Calvin clearly states as much in his Institutes, I.15.2: “There can be no question that man consists of a body and a soul.” In this way, Calvin is in line with many of the great ancient and medieval theologians as well as the theologians of his own day—Augustine, Abelard, Lombard, Aquinas, Luther, and so on. To be sure, each of these theologians had unique ways of formulating the precise relationship between the body and soul, some emphasizing the unity of the human person more than others.

I would argue that Calvin’s view of the body and soul was dualist but not radically so. He is clear to affirm the goodness of the body and the unity of the human person that must be understood as body and soul.

Still, Calvin is clear that the soul is superior to the body. Most explicitly, Calvin sees the soul as the seat of the image of God since it is the soul, obviously not bodies, that is immortal, reflecting God’s own immortality. For Calvin, when the body dies the human person lives on because the soul is immortal. Calvin spends much time on the immortality of the soul, which is part of his broader focus on eternal life. For Calvin, whose own physical life was lived as a refugee with significant heartache and suffering, the promise of eternal life when the body and soul would reunite, was one of the foundational promises of the Christian faith.

Calvin’s View: Dangers and Opportunities

I would contend that Calvin’s anthropological dualism is (1) theologically defensible and the traditional position held by the majority of the orthodox Christian tradition, (2) can be dangerously distorted in theologically harmful ways, and (3) can provide helpful theological correctives and opportunities.

First, a dangerous distortion. An obvious danger in overemphasizing the soul is that the physical here-and-now becomes ignored or even worthless. One example in Calvin’s own thinking is his understanding of biblical instructions to those who are under various types of authority, even abusive authorities. In his sermon on 1 Timothy 6:1-2, Calvin advises that we are to serve God willingly “even when it is a question of obeying those who treat us badly and who are cruel to us.” The passage in question is talking about slaves, though Calvin extends the passage to be about all those who are subject to others.

One can see the small step towards forbidding slaves to escape or revolt, advising wives to stay in abusive marriages, and so on. The danger in Calvin’s dualism is obvious: if we are just passing through on our way to heaven, then what we do or endure here is of lesser consequence.

On the other hand, Calvin’s emphasis on anthropological dualism does provide theological cautions for Calvinists overly eager to establish God’s kingdom in this physical world. Here Christian nationalists offer a prime example of how dangerous ignoring the soul and over-emphasizing the physical can be. If the soul is left behind so the physical here-and-now is all that matters, then everything hinges on establishing the kingdom of God in the world we inhabit. Is it any surprise, then, that Christian nationalists might claim a Reformed tradition which empowers them to claim every square inch in this country for Christ?

Perhaps Calvin’s emphasis on the soul can remind us that our lives are more than a moment in time. Perhaps Calvin’s emphasis on the spiritual can remind us of Christ’s words in John 18 that his kingdom is not of this world. Maybe Calvin can remind us, in a chaotic and confusing, world that we were created to follow Jesus through the power of the Spirit here and now and for all eternity in the new heaven and new earth.

6 Responses

I eagerly look forward to a condensed lesson in Calvinisim. Thank you Prof. Dieleman

I love this essay, this entry point in to the topic, and this conversational event! Thank you, Kyle.

It seems like the tradition of body/soul dualism tries to introduce an escape hatch out of the fact that a human is 100% mortal.

If our soul never quite dies, then bodily death is not so awful, right?

I think fear and dread of the fact of our 100% mortality is capably addressed in Christian orthodoxy through the announcement of the birth of a God who became so fully mortal that he was able to be completely killed. And then, surprisingly, through the announcement of a postdeath event in which the Grave, the most desolate place in the cosmos, births an immortal body from a completely dead and mortal body.

Immortal soul ideas in dualism seem to minimize the total tragedy of Death’s and Grave’s irrevocable deadend.

Total deadness and “no way out” desolation is the prerequisite for the apocalyptic plot twist of comic relief:

The ridiculous news is that Death and Grave get to become parents of an innumerable multitude in spite of their hopeless condition of infertility + menopause, as foreshadowed in the Abram Sarai story, and subsequent remembering prophecies about a people recalling the quarry out of which they were hewn.

After firstborn Jesus crowned, Death and Grave no longer can ignore that they’ve been blessed with the laughable task of nativity. . So many more resurrected and newly immortal bodies to come. What an escalation to all the improbable stories of infertile women, virgin women, and menopausal women birthing their own miracle, yet mortal, babies.

Jessica,

This is quite wonderful. Thank you!

Kyle,

I find what Jessica has to say a great answer to what I think is the heresy of an immortal soul. I can’t do better.

But, I don’t think Christian Nationalism is “this world” focused because they fail to see the importance of the soul and it’s immortality, and therefore, they are too focused on “Kingdom” building.

Every Christian Nationalist I’ve ever met, including a number of these people in my church insist on the immortality of the soul. Rather than abandoning the eternal nature of the soul (if it is even eternal), I think they misunderstand the nature of the “reign of God.” It is not a “this world” kingdom but an introduction to the Way of God in Christ exemplified by the death, resurrection, and ascension of Jesus. This is the “reign” of God and while it has implications for the world we live in and how we live in it (mostly the exact opposite of Christian Nationalism), it is about how the people of God are shaped, how God lives and interacts in the world, and how creation is renewed (and certainly much more).

It is precisely because Christian Nationalist misses this fact and the nature of the human soul found in Christ, that they go the opposite way of the vision of God in Christ. As you said with Calvin, this is a rather shallow explanation and more can/should be said, but its a simple response at best.

It seems clear to me that Calvin caught and highlighted God’s love for his creation. Calvin went so far as to call creation one of the books of revelation. God has and is making himself manifest to us through creation. Christ’s work of reconciling all things to his Father is yet another pointer towards God’s great and continued love for his creation. Calvin himself was fond of and occasionally quoted Greek and Roman philosophers. I think that it cannot be overemphasized that Calvin had a great reverence for the “physical” realm of creation. It is only fair to bring this view of creation to his anthropology. It goes without saying that I am eagerly anticipating your future submissions on Calvin.

Thank you for your thoughtful work.

Doesn’t our use of the the term “immortal” (as in “the soul is immortal”) tend to run together two distinct questions. One is whether there is, at the core of the human self, something that transcends a body made of organized carbon-based physical matter, and survives the death of that body. The other is that this core is–by its very nature– immortal, i.e., can itself never perish. If one opts in favor of Christian dualism, along the lines well articulated by Dr. John Cooper, I think one might do well to consider that souls, being created things, continue to exist only by the continuing active sustaining power of God. They are not by their nature “immortal” and “imperishable” as God must be held to be. How long a soul –(or a soul reclothed with a resurrected spiritual body, if one agrees with Paul that all humans will be resurrected for final judgment– — continues to exist after death would depend entirely upon God. John Stott thus came to think, as one live theological option, consistent with Scripture, that a God of merciful love might limit ‘hell’ to a limited duration of punishment for the obdurately impenitent. This is not a theological option if one thinks that the soul by its nature is “immortal” and indestructible in the same way God is immortal. To suppose immortality in *that* sense is entailed by being divine image bearers strikes me as dubious: did Calvin have an opinion on *that* question?