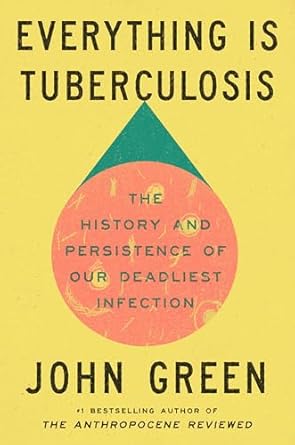

A tuberculosis outbreak began in the Kansas City, KS area in January of last year (2024). The outbreak is ongoing, with seventy confirmed active cases and 103 confirmed latent cases. Two people have died as a result of this TB outbreak. I took notice of the outbreak because my research seeks to discover bacteriophages that might be effective in fighting multidrug-resistant tuberculosis (TB). I followed tuberculosis outbreaks globally but did not expect one in my backyard. For these reasons, when I saw John Green’s newest book, Everything Is Tuberculosis, in the library, I immediately checked it out and got reading.

John Green is best known for his young adult (YA) fiction. If you have not heard of The Fault in our Stars or Turtles All the Way Down, ask your kids or grandkids. Everything Is Tuberculosis is a genre switch, joining his best-selling collection of personal essays and first nonfiction book, The Anthropocene Reviewed.

Green’s interest in tuberculosis began when he and his wife took a trip to Sierra Leone to learn more about the global maternal mortality crisis. At the Lakka Government Hospital, supported by Partners in Health, Green met Henry and his world changed. Seventeen-year-old Henry was about the size of a healthy nine-year old. He was a resident of Lakka, struggling mightily with multidrug-resistant tuberculosis, a disease he’d been fighting since he was six years old. Upon returning home, Green turned his attention to learning and writing about tuberculosis and this book was born.

Everything is Tuberculosis is an apt title for his book which is both short and expansive. In only 200 pages, Green connects tuberculosis to racism, fashion, beauty, poverty, wealth, power, and injustice. His arguments are tremendously persuasive.

Green points out that, historically, tuberculosis or consumption was believed to be a disease of the wealthy, white, elite. The pale, thin, large-eyed look of a woman with tuberculosis was seen as the definition of beauty in the nineteenth century. Most North Americans and Europeans believed TB was hereditary and associated with sensitivity and artistic talent.

Perspectives took dramatic turn when Robert Koch discovered the causative agent of TB, a bacterium called Mycobacterium tuberculosis, in 1882. It took less than a decade after his discovery for tuberculosis to be stigmatized as a disease of poverty and people of color.

Understanding that TB spread primarily through the air placed a focus on hygiene, influencing skirt lengths, beard popularity, and social behaviors such as kissing babies and public spitting.

During the first half of the twentieth century, countless people from all social classes were sent to TB sanitoriums, contradicting, as Green points out, the notion that TB was a disease of low status.

By the mid-1900s chest X-rays and a handful of effective antibiotics rendered TB curable—for those with access to healthcare. Countless people around the globe lacked access to diagnostic tests and effective drugs throughout this time and as exemplified by Henry’s story, still do.

In Henry’s story, Green tenderly shows us what a TB infection is like in the developing world and why multidrug resistant TB is all too common. Even today, most people lack access to the most effective tests to diagnose TB and as a result, doctors cannot diagnose the disease until the bacteria have already established an infection that is difficult to treat.

Treatment is lengthy. Patients need to take a combination of antibiotics for six to nine months. The drugs and expensive. Patients are typically required to go (often daily) to a clinic to get their drugs, and the clinics can be several hours away by bus or on foot. The obstacles are so overwhelming that many patients are “non-compliant” for good reasons and interruptions in treatment leads to multidrug resistant strains of TB.

What I found so compelling about Green’s book is how clearly he lays out the systematic problems that have continued to make tuberculosis a leading cause of death worldwide (1.25 million in 2023). With the funding cuts made by the Trump administration to organizations, like USAID, with programs to address the problem of TB, things have only gotten worse.

Poverty, race, colonization, stigmatization, transportation, and politics all work together to perpetuate the suffering tuberculosis patients experience. Green leaves us with this challenge: “We cannot address TB only with vaccines and medications…We must also address the root cause of tuberculosis, which is injustice. In a world where everyone can eat, access healthcare, and be treated humanely, tuberculosis has no chance. Ultimately, we are the cause. We must also be the cure (p. 184).”

This book will stay with me. I plan to share it broadly, including making it required reading in my Immunology course next semester. This well-written, accessible book is for anyone who longs to be the cure because being the cure has to begin with an understanding of how we are the cause.

The end of Henry’s story is a happy one. He completed his education, is a TB advocate and successful YouTuber, but the words he wrote to his mother while he was in Lakka Hospital haunt me.

Mom you are special and beautiful

You stand closer

When everyone ran away

Especially my cousin ran away

But you stood firm (p. 89)

I am grateful that John Green further opened my eyes to the systematic injustice of health and disease and I pray that we all find ways to stand closer to those who suffer.

Cover image credit: Tuberculosis Vectors by Vecteezy

6 Responses

Thanks for this thoughtful review. It sounds like a book well worth reading, and I plan to do so. I have a personal connection to TB. My dad emigrated from Friesland to Canada in 1951, and a few years later he contracted TB, spending an extended period in a sanatorium. The only good thing about that time, he used to say, was that it’s where he learned to play cribbage, a game he loved for the rest of his life. Stories like his remind me of how far we’ve come in fighting this disease but also how important it is to keep working to eliminate TB. Reading Green’s book will be another good reminder.

Thank you for this article. Opening our eyes to another example of the “systemic injustice of health and disease” illustrates that the “right to life” doesn’t end at birth.

Fascinating! I’m a fan of Green’s books and am anxious to read it.

This is heart wrenching to me. Our son who had Down syndrome died of TB that was only diagnosed after he died.

During our time living in the rural Philippines in the 1970’s virtually 100% of the population in our region carried the TB germ, and many suffered deformities or death from it. Two of our three children received the BCG vaccine as infants and did not develop TB. Our other child contracted amoeba dysentery in the hospital at birth and therefore could not be given the BCG. He subsequently contracted TB. He was treated and suffered no long lasting effects. Despite the resistant strains now raging in some locations, TB is still usually treatable for those of us with the resources, and is still often deadly for the majority of the world that does not. This is one more case where all it takes to save lives is the willingness to invest in their care.

Wow, Sara, there you go again. Brava.