It was around 1980 that Trisha Zinger and I starred in what had to have been the best children’s Christmas program of all time. While we were the lead, the supporting cast wasn’t all that bad either. The lifeless doll baby Jesus, the shepherds in their simple robes carrying their staffs. The wisemen wore their fancy outfits and offered their fancier gifts.

Many churches now buy elaborate programs with cheesy puns that most of the congregation can’t hear, but I am a fan of the old school simple story. A young girl playing Mary, who’s probably closer in age to the mother of our Lord than we’d ever imagine. A grumpy inn keeper telling this desperate couple “There’s no room!” Mary and Joseph, angels, shepherds, wisemen, and even a few animals gather around the manger throne of the helpless deity. It’s nostalgic and it’s beautiful. It’s just not biblical.

The Christmas story is one of the most cherished narratives of the church. God, in human form, came as a light in the darkness. And yet the story we tell is not really found in Scripture. First, neither Mark nor John even include a birth narrative. Mark begins his gospel at Jesus’ baptism. Maybe he isn’t familiar with the infancy narrative, or maybe he doesn’t see it as important for his work. John too passes over Jesus’ birth. Rather he highlights the eternal presence of the Word. Only Matthew and Luke tell the story of the nativity.

When our minds turn to the Christmas story, we often harmonize those two accounts. There is no biblical story that includes wisemen and shepherds. Don’t get me wrong, I don’t think combining these stories is wrong. I’m no Scrooge. But there is beauty in also pulling them apart to see what each writer was trying to say. And in doing so we might just learn more about the Jesus that their respective audiences, and maybe us, need to meet. This month and next, let’s look at what each gospel might teach us.

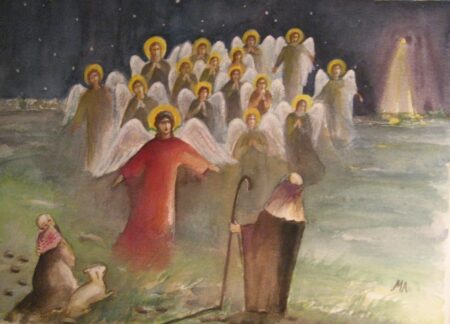

Luke’s nativity is the most familiar. The mighty Caesar Augustus speaks and the world moves for a census. Included in the move is a scandalous engaged couple who travel to Bethlehem. The child she carries is no ordinary child. The shepherds are told to go find the baby. Not just an ordinary baby but the “Savior. . . who is Christ the Lord.”

Those are loaded terms. To us they point to the special nature, or perhaps divinity of the child. But to Luke’s gospel these titles of rebellion. Savior, Christ, and Lord were titles reserved for the emperor. To ascribe them to anyone else would be treasonous. And yet the angelic chorus sings the truth, that in the midst of the darkness, a new empire has dawned. The real Savior, the real Christ, the real Lord had finally come.

Luke’s gospel does not just challenge the emperor, the gospel pushes against the empire itself. Most significantly, Luke’s new kingdom upends our understanding of power. Unlike the other gospels, Luke’s birth narrative, and really his whole gospel, prioritized the lowly and those on the margins. In opposition to the magnificent Roman places, the true Lord is born in humble circumstances. Whether it be a cave on the outskirts of Bethlehem or the ground floor of a house in which the animals would sleep at night, the point is the Son of God finds his abode amongst the poor.

Furthermore, in a world that was based upon a desire for upward mobility, who you hung around with was paramount. The emperor’s senators and equestrians were nowhere to be found. Rather the new king was surrounded by shepherds. The new kingdom was not primarily for the mighty, but the lowly, as shepherds represented those on the margins of the workforce. If this isn’t clear enough, Mary’s song in Luke makes it abundantly clear that Christ came to raise up the poor and bring down the mighty. But make no mistake, the infant surrounded by the smell of animals who will become the man who suffers on a cross is not powerless. Just the opposite. Just as true life will only come through death, so true power will only come through submission.

The kingdom brought power but it was also meant to bring peace. As opposed to the Pax Romana in which peace would only come through fear and force, the peace that this infant would offer would come through service and sacrifice. It would not be a peace from the empire but a shalom that could be found even in the midst of it.

Maybe Luke’s Jesus is the Jesus I need this season. In a world in which the seemingly powerful continue to prop up themselves at the expense of the poor: In a season where the mighty continue to menace the marginalized all in the name of law or, even worse, piety: I am renewed and refreshed that God enters in exactly at that moment and invites us to a better way. I am hopeful that I, at the same time, am the recipient and ambassador of that gift.

For the poor, for the broken, for the marginalized, for me, O Come, O come Emmanuel.

11 Responses

The Empire is back. …” the mighty menace the marginalized in the name of the law, or worse, in the name of piety.”

Thanks for bringing Christ back into Christianity.

This is excellent. Thank you, Chad.

“…the peace that this infant would offer would come through service and sacrifice.”

Am I willing to share this peace to others, no matter the cost?

Your last sentence is exactly the Jesus we should be looking for this Christmas! “For the poor, for the broken, for the marginalized, for me, O come, O come, Emmanuel.

Thank you. This is exactly what I needed to read today.

Thank you, Chad. You are teaching us how to read scripture deeply, and well. (Here and in all your posts, actually. This is a gift we need.)

This is excellent, Chad. Thank you for your enlightened teaching.

Thank you. Now you have made me curious about the framing and purpose of the Magi story…

Luke’s Jesus is definitely the Jesus I need this season.

Thank you

Chad, thanks for highlighting Luke’s account. I’m glad the church wisely chose to include four different gospels, each with its own unique framing of the Jesus story. What if we only had Matthew? Think what we’d miss. Although he has his own challenge to Empire.

Chad, I loved reading your article. I also love reading progressive Christian meditations. Your article reminded me of Dawn Hutchings sermon of the subversive birth of Jesus. I quote just a small section.

“Caesar offered a vision of a god who is born in a mansion, but this new vision of the Divine was born in a manger. Caesar is a god who enslaves. Christ is a God who sets free. Caesar is a god who lives with the oppressors. Christ is a god who is among and with the oppressed. The stories of Jesus birth are subversive stories designed to say a big No to the powers of Empire; to turn the world we thought we knew upside down and point to a new way of being in the world.

The story of Jesus birth represents a politically subversive call for us to enlist in a cause where we care for our neighbor, look out for the stranger and embrace the flesh and blood of those who are suffering, oppressed, persecuted, starving, homeless, those who have no voice.”