A number of you posted helpful responses to my first entry in this mini-series on creeds and confessions. I’d like to focus on one theme in particular, alongside some other reactions from our church-school series on the subject.

The class’s greatest discontent, as I noted last time, concerned the Reformed Standards’ treatment of Christ’s atonement as (almost solely) penal substitution. Other questions grew out of that, while still others were free standing.

Deep Context

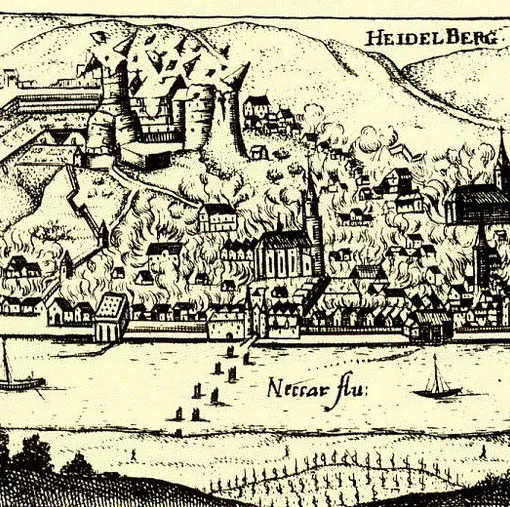

I’m a historian and not a theologian, so I’ll let people who are better trained in that domain speak to doctrinal specifics. Here, let’s return to the context surrounding the three classic Dutch Reformed Standards: the Belgic Confession, the Heidelberg Catechism, and the Canons of Dort. We’ve already seen how political circumstances informed these statements, but the matter of context goes broader and deeper than that. The whole mindset of their times, the framework of cultural assumptions, the things unknown on the one hand and taken for granted on the other, are so different from ours as to make appreciating these Standards a challenge.

It’s not that they’re wrong and we’re right; it’s that the 16th and early 17th centuries are such a distant country that statements formed in that matrix might have limited resonance in our own. (Pace John Haas: I mean “resonance” to connote not the mood of the moment, á la your reading of “relevance,” but a deeper register nested in a person or group’s cumulative experience.)

Establishment Needs Hard Definitions

So what did Reformation-era people assume or believe that makes it hard for us to “relate”?

First, the church was part of the official establishment almost everywhere in Europe and far more central to the functioning of society than it is with us. Formal rule and informal custom could hardly be imagined without it back then but certainly can be—must be?—in North America today. Likewise, although the Reformation did its part in starting to dissolve them, prevailing social theory of the times assumed that a person inhabited set structures and unchanging roles. Thus the Standards enjoin us to fulfill prescribed moral duties, not—as today—to think of fluctuating social systems amid which we, together, must sort out our witness to the reign of God.

Second, its privileged—indeed, essential—place in upholding order made it all the more important for the church to get its doctrine right, and the fragmentation of Roman Catholic unity meant that rival Protestant families had to distinguish their definitions from those of several rivals. One consequence, frequently lamented by our class, is that the Reformed Standards insist on boundaries, divisions, and internal uniformity while we yearn for bridges, unity, and internal diversity.

Yet my colleague and I pointed out that statements which progressive Protestants favor—like the Barmen Declaration and Belhar Confession—draw their own lines in the sand and warn against crossing them. Belhar in fact deliberately (?), cheekily (?), imitates the Canons of Dort in specifying erroneous teachings and behaviors that are to be rejected. The need for boundaries evidently has not disappeared; it’s the things proscribed that have changed. Even so, the ecumenical mood in the air today makes the Standards’ hard-and-fast prescriptions more difficult to take.

Feudal, and Futile, Hierarchy

Third, Reformation-era people inherited feudal hierarchy as a model of God’s character and the divine-human relationship. Not only did this elevated “lord” possess all “majesty” and deserve all “glory” but his “honor” was that which our sin intolerably besmirched, an offense that demanded full “satisfaction.” Now these are not only the premises of penal substitutionary atonement; the words in quotation marks are functionally foreign to us. We readily apply majesty to nature but not to people. We’ve long gotten rid of lords (even if they’ve crept back in through the side door under different names). Glory might still hover around high school athletic trophy cases, but the satisfaction of honor went out with dueling and other frights of the slaveholding South.

In short, we recite these words but do not live them. Instead, God has either become remote and absent, the world spinning along under the rule of natural laws and predictable social dynamics, or has been swallowed up by sentimentality. Jesus as boyfriend, the terrifying angels of Scripture reduced to befuddled grandpa Clarence in It’s a Wonderful Life. Surely there’s a sweet spot in between, but it’s hard to find with our Confessions’ foreign language.

Dealing with Sin

Finally, or maybe first of all, Reformation-era folk seemed profoundly anxious about the demands of God and the remote likelihood of their own salvation. See Martin Luther’s famous Anfechtung, spiritual doubt ramped up to outright terror and despair. The man met the moment so spectacularly because he was not just speaking for himself but for vast swathes of people. Princes endowed chantries where thousands of postmortem masses could be sung for their sorry souls; common folk had to make do with purchasing indulgences to hasten their transit through purgatory. Purgatory itself had been introduced as a device of comfort, an escape path from the damnation so many obviously deserved at the moment of death, only to evolve into a place of prolonged torment.

Maybe it’s because our lifespans are so much longer, our levels of material comfort so much higher, our vulnerability to the fickle finger of fate so much lower—with “fate,” besides, conceived as the hand of God lowering bad news out of his wrath. In any case, modern people don’t seem to share this dread. Will Herberg’s famous Protestant Catholic Jew of 1955 reported Gallup polling in which virtually all Americans professed belief in an afterlife but fewer than 15 percent thought hell to be a real possibility for themselves. For post-moderns, to the extent that God, or a higher power, is thought to exist at all, his or her or its principal function is to assist people on their quest to being happy, affirmed, fulfilled, and ultimately a “good person.”

Translating Sin

Yet that’s not the whole story. By all reports, good old anxiety has come roaring back; loneliness too. The consultant who helped our church through its recent visioning process, himself a Lutheran, drolly reported that we Calvinists were out of luck in that Americans don’t feel guilty anymore. Instead, he continued, they are swimming in a sea of shame, which is a much harder syndrome to overcome.

It seems that the higher power ain’t coming through consistently. How might the gospel speak more tellingly in our current malaise? Perhaps if the concepts of the Standards were translated into, or supplemented with, more resonant terms. The Standards inherited and perpetuated Western Christianity’s notions of sin as a debt or legal offense. How about mining Scripture’s other language instead, or besides: sin as being lost, alienated, abandoned, afflicted, broken, wandering from the right path, or the Catechism’s own category of “misery”?

Picturing the Confessions

Last time I said that I would take up the question of what, in the light of all the difficulties they present, the Confessions are good for. This post is already getting too long, so for now let’s look briefly at how we might picture their functions. My colleague and I came up with five images; you can probably suggest others.

First, the Standards have served as walls, high and thick, designed to keep bad ideas out and true ideas in, all clear and well defined. There are gates into this city, but as some Christian Reformed folks have recently discovered, these can double as guillotines.

Second, changing the image from static to dynamic, Confessions can act as guardrails, keeping churches on the move from veering off into trouble on one side or the other. Most often the dangers are thought to lie on the left, “liberalism” and all. But Belhar and Barmen mark them on the right, and so once (in 1918) did the Christian Reformed synod in pronouncing the premises of “end-times” dispensationalism to be heretical.

Keeping with the road image, thirdly, we can see the Reformed Standards as defining one lane on the broader highway of Christianity, next to those traveled by Lutherans, Anabaptists, Wesleyans, etc. You can move from one lane to another with proper signaling, but the traffic of theological conversation and Christian cooperation moves better with clear markings and mutual respect.

Fourthly, Confessions can function as the deep roots of a tree, providing nourishment and stability that enable the church to stretch out its branches into a canopy of shelter, beauty, and vibrant life. They feed us on the wisdom of the past and keep us from being blown about by every wind of doctrine, be it the gas of theobros or the wafts of potpourri in the megachurch mini-mall.

Finally, Confessions might be lengths of an anchor chain that ties a ship firmly to Christ with each additional extension enabling it to expand the reach of the gospel and discover new waters for the gospel to comprehend.

Which image do you prefer, or which other would you nominate?

Header photo by micahel biney on Unsplash

Anchor chain photo by Just Nobody on Unsplash

24 Responses

I like trees. In their two excellent chapters in the RCA’s commentary on the Heidelberg from 1963 called Guilt, Grace, and Gratitude, Eugene Osterhaven and Gene Heideman laid out the shortcomings of the Catechism on Atonement, Holy Spirit, and Ecclesiology as conditions of its context, somewhat as you have done above. But the value of the Catrchism on Atonement, argued Osterhaven, remains in our knowing (and being grounded in) what the Western Church Catholic believed for many centuries, while not being confined or limited or straitjacketted therein (unlike the CRC). The Catechism itself, in its language on the Sacraments, has hints of a covenantal doctrine of the Atonement unknown to Anselm or the Roman church, but which the Catechism does not develop, probably partly because of its peace-keeping commitment to the reigning penal substitution consensus.

I believe that it’s important for Reformeed pastors to understand penal substitution, as indeed there are scripture verses suggesting it, and even suggesting “ransom,” but then also to move on to Our Lord’s own words about his death, that he called it a New Covenant, and in John 6 also Life to the world, and let these be the controlling doctrines of Atonement. And from that it follows that the best way for the church to experience and understand the Atonement is in the weekly Eucharist, the Easter dinner.

Amen and amen, Daniel. Thanks for reminding us of the two Genes’ deft and helpful navigating of the question. I think it’s just right.

This is so well laid- out and compelling. Thanks Jim! A few reactions to begin the discussion:

The feudal era began way back in Noah’s time already, even Cain’s. Might makes right. It is presumed in the OldTestament. And God MUST be angry in order to be just.

Hell is the church’s greatest marketing tool, so that card has always been overplayed.

St Paul reinforces penal substitution and original sin. But did he presume those as narratives of the day? believe those? or just see those as minors not to be majored on? How exactly does inspiration work and must it be paired with inerrancy? Would he write and strategize differently today?

Speaking of that, when we consider how large , sovereign, and long-suffering God is, must we also conclude that God forgives the church’s multitude of severe missteps?

The church is our best attempt to define the kingdom of God, but it falls short, constantly becoming its own empire throughout history. We MUST be humble. If God is not forgiving, we are ALL in trouble.

I like Daniel’s language a year or two ago. The catechism is a curriculum, not a rule book or measuring instrument for salvation.

Terms like heretical or salvific, applied to the catechism, are not necessarily helpful.

So…… chains and walls? Too prison-like. Guardrails? OK as long as the ruling body does not arrest and deport those who touch them. Lanes for us to stay in? OK.

I kind of like roots…. alive, growing and expanding if nourished and not smothered.

RZ,

Thanks for these thoughts. I offer a minor criticism. The Church is our best attempt to bear witness to the Kingdom of God. We do not define it, nor is the Church the Kingdom, part of it, of course, but not all of it.

I’m not sure any of that is what you meant with your comment, but I thought I’d offer that response.

RZ, I appreciate your willingness to interrogate Paul. In my opinion, he sets a great example of interpreting the gospel in his time, but then we ought to do the same for our time and not grant him the last word on it, i.e., the cross.

Thank you for a very helpful post for those of us who are re-thinking the role of these 500 year old documents play in our lives. I would point out that there is one community where the characteristics you describe still exist, and that is the military. Hierarchy is still very clear, “glory” is given to those higher up via a salute, the “Sovereign” (Commanding Officer) is “glorified” every time s/he enters a room by everyone standing up, and “honor” is a big deal. Could that be why those who want to control the thinking and behavior of others resort to military language (“culture wars”) with themselves as the never-to-be-unquestioned authorities on top?

Very interesting! You might be right in your speculation….

No degrees in doctrine or history here, other than a lifetime of shaping liturgy and worship, and having just finished “Holy Envy” by Barbara Brown Taylor, I’ll go with four and five: giving us freedom to question and discuss, grow and flourish. Just as Jesus listened to Nicodemus before explaining the mystery, why are we so loath to admit so much of what we believe is beyond human knowledge, and then rest in that mystery? Giving us roots that grow deep and permit width.

I think this is a necessary and insightful deconstruction; but I also sense the death throes of modernism. The allusions to ships and anchors brought to mind Acts 27:19: “On the third day, they threw the ship’s tackle overboard with their own hands.”

Perhaps the way forward is outside the bounds of Western Civilization toward the styles of Rohr or D.B. Hart.

I’ll go with the tree image, found throughout the Bible. And I’ll wonder with hope about “the leaves of the tree are for the healing of the nations.”

One of the best sermons I ever heard was a chapel talk by Neal Plantinga on that very verse. Thanks!

It’s hard to over-state how good this is.

A question does arise. It’s been the rage for some time among folk like us–enamored, and rightly so, with our beliefs in equality and thus diversity, of the inviolability of individual conscience and freedom, and also simply assuming that the goal of life is to discover and then live out our “authentic selves” (such as those may be)–you hold institutions (such as churches) somewhat more lightly than in the past. If you’re historically minded, you’re also all too aware of how human, all too human, all these various doctrinal and ecclesiological traditions are: how contingent are their origins, how immersed in the political have been their developments, how tainted and besmirched by compromise, hypocrisy, greed, pride, and all the rest.

Between all the inducements to center the self (both as a means to succeed but also as a mandate of justice–“to thy own self be true” and all that–and the complications of navigating a pluralist society and the acids of modern awareness walling us off from the naive and unquestioning loyalties of the past, we have a whole lot of folk in our various Reformed communities whose catechisms reserve a privileged place for Iris DeMent’s conclusion: “I think I’ll just let the mystery be.”

For those raised in the more authoritarian, intolerant, closed-minded, prescriptive, uniform, etc., etc. communities of the past, the current trend of floating uncertainly and non-judmentally upon whatever flow seems attractive feels like liberation. And it is. I don’t want to go back.

But for younger people–or many of them at least–the framework of cultural assumptions is a bit different. They may have never heard John Calvin quoted as an authority, or, if he was, it came with an apology. They’ve never been pressed in catechism class with arguments for why their tradition is *better,* and therefore worthy of their allegiance. They might never have been really catechized. I’m no sociologist, but I keep hearing rumblings about how younger people are thirsting for more confidence, more certainty, for firm foundations–boundaries even, if not walls.

I’m not at all sure of this, but I do wonder if our churches aren’t so oriented towards avoiding the mistakes of a narrow-minded confessionalism that that they’ve forgotten that the distortions its older members have developed allergies to aren’t the obsessions of their children and grandchildren.

I get the same vibe about younger people, which is why it’s important to check our own context for its limitations. I’ve never been a fan of Emersonian individualism in all its recurrent iterations, and very much vote for institutions as a necessary counterweight. Institutions open to self-critique and reform, that is. Thanks for the good word.

Jim,

Thanks for this excellent article. This week, I was listening to a podcast on what America is, and they talked about how often the founding “Fathers” referred to America as an experiment, how much they didn’t know, and how much they were making it up along the way.

Now we treat the constitution and our country as if it fell from the sky out of the benevolent hands of a good God, never to be changed or if the country has changed, we can only go back to its origins to be righteous.

I wonder if the standards might be treated in a similar way. Deep and abiding truths are found within, but what if the reformation is thought of as an experiment in our faith, diving deeper into the Word and stumbling our way through new ideas. If that were the case then we might treat the Standards like the “guide” they were always meant to be, not an end point in and of themselves. I might be sacrilegious enough to suggest the same could be said about the Bible. After all it is our best witness to Christ, but maybe not the only witness. At least I don’t think sola scriptura means we have no other way to know Jesus.

Anyway, I’m getting off track.

Thank you.

That’s what, I think, the RCA was trying to get at when they changed the declaration for ministers to say “I accept the Standards as historic and faithful witnesses to the Word of God,” from the old form, which had ministers say that they believed the Gospel to be “truly set forth in the Standards.” The Standards were the experiments of their time. I think we follow best in the footsteps of those who wrote them when we read, think, pray, and act in discernment of how to be faithful to God today, not perpetually rehashing how those in the past were called to be faithful to God in their times.

Many thanks, Jim. The scriptures have so many images and metaphors for salvation in Christ that it seems narrow and arbitrary to insist that only one of them is true. Victory over sin and death and the evil powers that threaten us is the one that grabs and holds contemporary African Christians. I love these centuries old testimonies to faith in Christ and to true doctrine. But context surely does matter. Do we really think that the writers of the confessions thought they had written once and forever statements? They were addressing current needs for clarification. We should too. Andrew Walls once defined theology as Christian thinking about new issues that have not been fully addressed before. So a metaphor for confessions? Timothy Smith had one that I like: gyroscopes to right the ship as we move through rough seas.

Yes, I like gyroscopes. Instruments for keeping us on course as we move forward into uncharted territory. And I think your African friends are living–hoping–by Christus Victory, which is my music!

Jim thanks for your thoughts, and also for stimulating good discussion and pondering. I had the privilege of teaching books like Job, Jeremiah, and Habakkuk for four decades and one truth I find in all three is that God cannot be put in a box, not even when that box is supported by proof-texts. Because I value these Biblical books I really struggle with those who believe they know the final word on who God is, what God values, and sometimes even how God thinks. Your reminder that the confessions were not written without context is very timely and necessary. I am looking forward to your next writing in this great series.

This is very good. I like the multi-lane highway imagery. But I’m afraid that the theobros will quote the “broad is the way…and narrow the path” passage to make the freeway into a narrow bridge over hell’s canyon. We need to know the historical context to avoid that.

Thanks again, Jim, for a thoughtful and thought-provoking piece. It’s worth noting, I think, that what you call “the [Heidelberg] Catechism’s own category of ‘misery’ [German: Elend]” actually includes the lostness and alienation that you mention earlier in the sentence, as well as connotations of banishment and exile. That nicely sets up the comfort theme in Q/A 1: The work of Christ makes it possible for people to move from non-belonging to belonging (to him).

Yes, thanks for the translation reminder. More from the German that you can add?

Rodney,

Thanks for the clarification. I cannot disagree. Your choice of wording is more theologically appropriate while mine simply describes what the church has often done in practice. I like your concept of “experiments.” Perhaps Wesley’s clarification describes what we both are trying to get at. “”I accept the standards as faithful and historical witnesses to the Word of God ” The RCA humbly checked themselves. The CRC, on the other hand, doubled down and said yes, in fact, we will define the kingdom of God. And, while we are at it, we will also define chastity and which beliefs are salvific.

What a refreshing discussion based on a helpful treatment of the creeds. I appreciate the broader metaphors for sin (thinking of Greg Boyle’s boots-on-the-ground preference for brokenness and unhealthiness) that expand the meaning of the cross in my opinion. Also the openness among respondents to regarding the creeds as experiments. What else can we do with mystery? As an RCA turned ELCA pastor, I bear with congregations’ insistence on reciting the Apostles Creed every Sunday. But I have resolved it by saying “I trust” instead of “I believe,” thus moving it to an avowal of a relationship more than assent to doctrine. It works for me.

In that last talk you gave in the basement of Eastern Avenue, Jim, I recall yet a further image you voiced. Perhaps it was an improvised spin-off from the tree roots image, but you briefly used the metaphor of of confessional traditions as rivers or streams, wasn’t it? How did that go? What most struck me was, near the end, you spoke of such a confession river as as emptying moving into “delta.” … We’d just seen that old film African Queen a few months back, where Charlie (Bogart) and Rose (Katherine Hepburn) find their African Queen boat trip on a wild river culminating with them lost in a swamp of mucky channels of barely moving water, full of leeches and with tall reeds towering around them. Not exactly a typical delta, I guess, but I would love to hear you recap how that improvised river metaphor went!