Our series on Sunday evening worship continues.

figure I have preached some 225 Sunday evening services, mostly in Ontario.

From my youth through college I attended about 600 of them, mostly in the Eastern RCA (Reformed Church in America). In the East, the RCA churches that had evening services were those with Second Immigration (post 1847) “Hollanders” in their membership.

During my childhood in Brooklyn we worshipped only on Sunday mornings, but then my dad took a church in the Jersey suburbs that had enough Hollanders to hold evening services. These were low energy. We sang dreary hymns like Beneath the Cross of Jesus, with dreadful lyrics like, “I ask no other sunshine than the sunshine of his face.” We got “special music” instead of the senior choir. On Communion Sundays we had the awkward “Second Table” for members who had missed the morning service—two pews of them, while the rest of us watched.

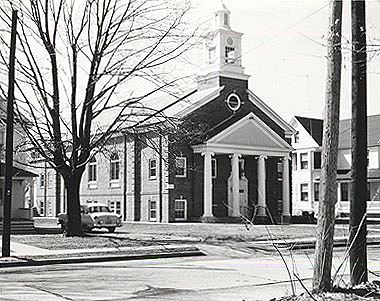

Four years later my dad took a call to a big church in West Sayville, Long Island, the only mostly-Hollander RCA in Metropolitan New York. Its evening services were more lively and sometimes enjoyable. There was a decent crowd with young people in the pews, and the senior choir sang for this service too.

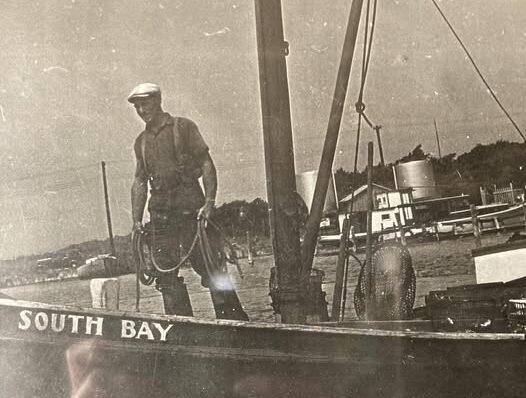

West Sayville had only two churches, Reformed and Christian Reformed Church (CRC). Hollanders defined the local culture, especially the fishing and clamming, but the village was by no means exclusively Dutch. First Reformed was robust and open, and was able to integrate the Burkes, Walkers, Paglias, a MacMillan, a Fleischmann, and all the Leigh-Manuels. With the smaller, colder CRC it shared inter-marriages but no love. The two congregations put plenty of people in church on Sunday evenings.

West Sayville was peaceful on Sundays. Nobody went clamming. The fire alarm was shortened to a single blast. I could listen to the birds on my morning walks. Walter Griek would be inspecting his flowers instead of trawling for fish. I waved to Bram Wessels and said “Goede morgen” to old Arie Schaper out on his little porch. The church bell rang at 8:00 AM for the early service at 8:30.

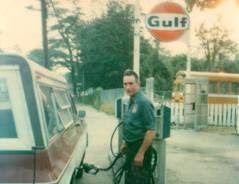

Our congregation was big enough to need two Sunday morning services, with Sunday School in between. The RCA was not rigid: we could walk to Bill Luce’s Dugout and load up on candy for the main service. A few men at the counter would be finishing their coffee. By then Bud Van Wyen would be in his robe for the choir procession; his Gulf Station closed all day.

After Sunday dinner, people would nap, or we might walk down to the docks, and see the clammers checking their boats or reading the sky. After a light meal of bread and tea (Dutch style) the church bell rang at 7:00 PM.

The bellringer was the sexton, Case Van Hulsentop, a post-war immigrant, his hands broken by the Nazis. After the bell he’d come out and sit on the church’s wide stoop for a cigarette. As other men arrived, the line of smokers would extend across the stoop. We boys knew our place and sat at the end. At 7:15 Case would go in to ring the bell again, put a glass of water on the pulpit, adjust the windows, and come back out until the final bell at 7:30. By then we’d all be inside.

The evening service was relaxed. We kids sat together unless we were in choir. One of us might get the honor of sitting on the organ bench with Mrs. Griek. She let Kathy Van Wyen play some evening services. Kathy was talented and fun, and once for her prelude she improvised on “I Don’t Know How to Love Him” from Jesus Christ, Superstar. Every year the Bay Shore Choraliers from an AME church would sing. We had guest preachers monthly to give my dad a break. After church was Youth Group, and after that a bunch of us would gather in the parsonage, often with my dad.

So two things. First, the character of the evening service had much to do with the larger context, especially if it was enveloped in a subculture that was lively, textured, and warm. What we had in West Sayville was lacking in suburban Jersey.

Second, as Debra Rienstra noticed, the evening service effectively made the whole day a Sabbath. If you were going back to church after supper, it made a difference in how you spent your afternoon: no shopping, no homework, no NFL. A quiet afternoon made a difference in how you got ready on Sunday morning. Sundays were mildly countercultural, and you had good company.

The cliché is familiar by now: “If you’re a oncer, your kids will be noncers.” But I think it’s less about losing the second service than losing a sabbatical counterculture—which in the RCA, at least, was modulated, humane, and even pleasurable. It was churchly and not political, but countercultural nonetheless. And that, we have not suitably replaced.