by Joan Zwagerman Curbow

If you have missed most of the movies of 2006, a number of them were available on DVD before the end of the year. Each of these films has garnered their share of attention in Hollywood, but for those of us outside the soundstage, they offer more than award nominations. Without bludgeoning, they touch upon two volatile issues–family values and 9/11–and this year Hollywood trumped the political arena by exploring these themes with subtlety and respect, honoring the humanity beneath the slogans.

While relationship movies were not in abundance in 2006, one worth watching–Little Miss Sunshine–centers around a fractious family who literally throws itself into a yellow VW bus on a misbegotten mission. When we first meet the Hoovers, it is dinnertime, and Sheryl, the mom (Toni Collette), comes home with her brother, Frank, fresh from a botched suicide.  Avoiding such painful details would be a challenge for most families, but watching this frayed group grapple with a touchy situation, while they can barely tolerate rubbing elbows, is mesmerizing. The family dynamics are not as raw and corrosive as the Berkman family inThe Squid and the Whale, but their dysfunctionality is palpable.

Avoiding such painful details would be a challenge for most families, but watching this frayed group grapple with a touchy situation, while they can barely tolerate rubbing elbows, is mesmerizing. The family dynamics are not as raw and corrosive as the Berkman family inThe Squid and the Whale, but their dysfunctionality is palpable.

Dad, Richard (Greg Kinnear), is a selfappointed self-help guru, who desperately longs to be a “winner,” even though he fails to draw even small crowds to his seminars. His wife, struggling to financially support her husband and emotionally support her brother, wants to be loving and truthful, but she also wants her husband to be a success and her chubby daughter (Olive, aptly named as she resembles the relish) to be a pageant winner–two things we know will never happen.

Still, events conspire to put Olive in the running for a title, so the family cram themselves into their decrepit van to race from Albuquerque to Redondo Beach, California. Along for the ride are Dwayne (Paul Dano), Olive’s sullen brother who loves Nietzsche and whose vow of silence elevatesincommunicado to ridiculous extremes, an irascible heroin-snorting grandfather, and Frank (Steve Carell, in a wonderfully controlled performance). On the road, with too little time and money, they head for the family’s one hope–the beauty pageant–and what ensues will either be an extended sitcom or a surprise.

Much of the time, the film offers pleasant surprises. You have to admire the way the Hoovers hold onto hope: Dad wants a book deal, Dwayne wants to be a pilot, Olive wants to be deemed beautiful, and Mom wants everyone’s dreams to come true. Frank’s presence, however, is a corrective to all these cockeyed dreams. He’s a living example of how frightening it can be to have your hopes crushed, and given that none of these dreams seem very possible, we fear for this brave little band careering down the interstate.

Along the way, the dreams begin to unravel as Richard discovers he’s been getting the run-around, and Sheryl realizes she’s hitched her wagon to a crashing meteor. When Frank explains to Dwayne the reason he’ll never make it as a pilot, his breakdown is immediate and forceful. Taking on a desolation that would have made Elijah proud, Dwayne collapses on the scorched desert floor. Directors Jonathan Dayton and Valerie Faris place the grownups at a remove, blocking them on an embankment in the distance. The strength of the horizon–the road, the van, the family–form a hard line, a sharp delineation between Dwayne’s bitterness on the yellow earth and a deep blue sky overhead. Typically, such a sky is a symbol of abiding hope, but here it is also a rebuke, for it is mottled with thready clouds that are reminiscent of jet trails. People with hopes and dreams and means–people going somewhere–would be in that sky, on those jets, whereas this family has run aground.

Yet Olive, in bright red cowboy boots, her belly heaped like a Buddha–looking less like a beauty queen than ever–clomps over the cactus to sit with Dwayne. This poignant tableau calls to mind the way Bruce Beresford captured rural Texas in Tender Mercies. There are many fine moments, such as this one, in this movie, but there are problems as well, and they tend to center around Grandpa. Alan Arkin does as good a job as could be expected of a stock character, but isn’t it time to put the foul-mouthed, randy, elderly character out to pasture? Oh, wait, the movie goes one better by having him die partway through the trip. It’s as if the screenwriter realized that the character had no arc, no hopes or dreams, only regrets that he didn’t shag more women when he was young. The movie falters into farce at this point as the family debates over what to do with the body. All in all, Grandpa’s character is dead weight in more ways than one.

A bigger problem with Grandpa centers on his legacy to Olive. He looked after her and was her talent coach, and his love for her is obvious, but, given his jaundiced view of life, didn’t anyone in the family question that role? When she performs, what is meant to parody the exploitative aspects of young girls’ beauty contests, her own dance comes across as exploitative. The routine is a reflection of Grandpa’s own narcissism, with little thought of the consequences to his granddaughter. When the rest of the family realizes that, they rush in to save her, but what is intended as an exercise in family bonding and protection devolves into bad movie-making. This film, which makes some wonderfully acute observations about family life, falters badly at this point by taking the cheap way out in this scene.

Still, much remains to enjoy about this film; the early scenes are finely drawn, and all the actors infuse their roles with passion. Much has been written about Abigail Breslin’s performance as Olive (receiving a Best Supporting Actress nod), but, for my money, Steve Carell steals the show when he runs as though pressed between two panes of glass or when he recounts his failed suicide. If such a thing can be funny, he has pulled it off.

***

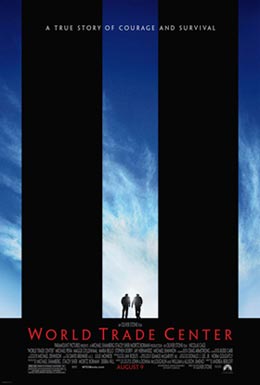

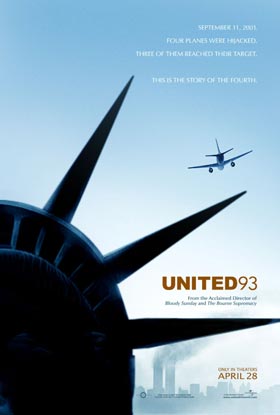

If there is a prudent waiting-time for movies to be made about terrible events, who determines how long to wait? Some felt that such time had not elapsed when two movies were released last year (World Trade Center and United 93 ), both based on events of September 11, 2001. Perhaps it’s useful to remember that in 1975 President Ford declared the Vietnam War finished, and the first post-Vietnam War movie appeared in 1978, The Deer Hunter, followed by Apocalypse Now in 1979. Of course, there are differences between the post-Vietnam and the post-9/11 storytelling methods, one of them being that the Vietnam movies focused more on the myths, on what it meant to live through the hell of the war in southeast Asia, and the movies following 9/11 have striven to be faithful to the facts of a more isolated event.  Too, the post-Vietnam movies captured a diffuse, collective experience through the means of fiction, while the post-9/11 movies have focused on real people’s lives. In that sense, one can appreciate why family members in particular might have been hesitant for such movies to be made this soon.

Too, the post-Vietnam movies captured a diffuse, collective experience through the means of fiction, while the post-9/11 movies have focused on real people’s lives. In that sense, one can appreciate why family members in particular might have been hesitant for such movies to be made this soon.

The post 9/11 movies examined here tell stories of heroism rather than jingoism; they focus on personal drama instead of political dramatics, and in this, they succeed quite ably. That one of these movies was directed by Oliver Stone, a man who has chosen venues that seem to feed on the grandest of film-making gestures, makes that success a nice surprise.

Stone’s movie, World Trade Center, depicts the eponymous attacks in downtown Manhattan and centers on two real policemen who were trapped in the rubble after the Twin Towers collapsed. A dedicated Port Authority police captain, John McLoughlin (Nicolas Cage), leads his men into the fray of the wounded buildings, and we know that most of them will pay with their lives. When the towers crumble, McLoughlin and two of his men survive, although one dies shortly after. The bulk of the movie cuts between the trapped men, McLoughlin and Will Jimeno (Michael Pena), and their families as they worry and wait. The film contrasts the darkness of being buried alive with the beauty of that clear September day.

Watching this movie on a small screen rendered the scenes even more dark, with faces barely visible through the gloom, and Oliver Stone, in his director’s comments, says he strove hard to avoid that happening on the big screen, but the muddy home quality is not necessarily a bad thing. The two men’s voices calling to one another in neardarkness heightens the sense of what it must have been like to have been trapped in rubble and confusion.

Of the two movies, World Trade Center is the more standard Hollywood issue, with some flashbacks of family life that edge toward the melodramatic. The movie’s biggest misstep is the larger-than-life depiction of Dave Karnes, a man who felt called by God to venture into Ground Zero and help rescue McLoughlin and Jimeno, but he’s played with such zeal that one wonders if he should have undergone a psych evaluation first. That the actor playing him bears more than a little resemblance to Stone, too, is unnerving, and one can’t help but feel that Karnes, who says, “I don’t think you guys realize this but this country is now at war” may be a mouthpiece for Stone, whether or not Karnes really uttered those words. In fact, the emotional pitch of the movie seems to echo war, an arena in which Stone found early success, and which may play the most true for him.

While World Trade Center focused on the buildings that were hit, United 93 looks at one of the planes destined to hit a building in the nation’s capital. This movie turns a more dispassionate eye on the people who died trying to divert the fourth hijack/ suicide mission on 9/11.  Because of a ground delay, the hijackers were thrown off schedule and the extra time alerted passengers and crew to the other hijacked planes. Determined not to be another “missile” they decided to overtake the hijackers and try to steer the plane away from urban areas. Director Paul Greengrass chose not to focus on the passengers’ backgrounds or even to introduce the people on board the f light that day, yet the film grips us from the opening scene. Those are Everyone–you or I–on that plane, ordinary people, living ordinary lives, but somehow these forty-some strangers undertook a doomed, yet life-affirming task: die fighting to stay a wrong action.

Because of a ground delay, the hijackers were thrown off schedule and the extra time alerted passengers and crew to the other hijacked planes. Determined not to be another “missile” they decided to overtake the hijackers and try to steer the plane away from urban areas. Director Paul Greengrass chose not to focus on the passengers’ backgrounds or even to introduce the people on board the f light that day, yet the film grips us from the opening scene. Those are Everyone–you or I–on that plane, ordinary people, living ordinary lives, but somehow these forty-some strangers undertook a doomed, yet life-affirming task: die fighting to stay a wrong action.

Greengrass chose an unusual lens through which to view 9/11: the conf lux of modernity versus medievalism. In the director’s comments, he talks about “two hijacks that day,” the one being obvious, but he saw the other as the hijack “of a religion, the selection of pieces of the Koran to create a …closed circle of belief.” So Greengrass’ approach is to watch the ways that the actions of Islamic fundamentalists eroded the means of modern life. A ll of the action takes place within those systems, cutting from the plane to various air traffic control centers to the military, never seeing the families of the passengers or crew, and this was a brave directorial choice. It accomplishes exactly what Greengrass was after, to ratchet up the sense of intensity and claustrophobia that the passengers must have felt, and to portray their sense of being abandoned by the supposedly sophisticated systems of their world.

Greengrass also made another interesting directorial choice in using some of the real-life heroes in his movie. He intersperses people like Ben Sliney, who was the national operations manager of FA A command in Herndon, Virginia, and Major James Fox and First Lieutenant Jeremy Powell from military operations with actors in the movie. It’s a seamless fit; the actors seem like real people and vice versa, but it makes this viewer wonder how they dared relive such a harrowing day.

It should also be noted that a TV-movie, Flight 93, was also released in 2006, but its director, Peter Markle, made different choices. While Director Greengrass felt it would be more powerful to remain in the “environment,” Markle chose the more standard route of showing the families, and there is plenty of emotional payoff in this movie, too. In fact, for some viewers this may be the preferred version. As the passengers head for the plane, their boarding passes f lash on screen with each person’s name printed on their tickets, and Americans and Jihadists go through the gates, side by side. When Todd Beamer’s conversation with a Verizon employee is re-enacted as they recite The Lord’s Prayer, it is a powerful and affecting scene.

The remarkable thing about both movies is their refusal to demonize either the four hijackers or Islam. Markle, like Greengrass, took great care to focus on the actions of the hijackers instead of their motives. The movies are “clean” in that way, devoid of the political morass and turmoil that these events plunged our government into. After five years of a war whose purpose continues to draw ire, it can be easy to forget that on a beautiful September day, a light load of passengers were soon to meet an awful destiny. Both 93 films and their filmmakers have done great justice to the heroic people on board that flight.