In January of 1966, the Reverend Benjamin Payton formed a new organization, the National Committee of Negro Churchmen (later the National Commission of Black Churchman, or NCBC). They released a statement on Black power, published as an ad in the New York Times.

We, an informal group of Negro churchman in America are deeply disturbed about the crisis brought upon our country by historical distortions of important human realities in the controversy about “black power.” What we see, shining through the variety of rhetoric is not anything new but the same old problem of power and race which has faced our beloved country since 1619.

We realize that neither the term ‘power’ nor the term ‘Christian Conscience’ are easy matters to talk about, and especially in the context of race relations in America. The fundamental distortion facing us in the controversy about ‘black power’ is rooted in a gross imbalance of power and conscience between Negroes and white Americans. It is this distortion, mainly, which is responsible for the widespread, through often inarticulate, assumption that white people are justified in getting what they want through the use of power, but that Negro Americans must, either by nature or by circumstances, make their appeal only through conscience. As a result, the power of white men and the conscience of black men have both been corrupted. The power of white men is corrupted because it meets little meaningful resistance from Negroes to temper it and keep white men from aping God….We are faced now with a situation where conscience-less power meets powerless conscience, threatening the very foundations of our nation.

The Black power movement made most Americans uncomfortable. Discussions about power are uncomfortable for the people in power, after all. The statement went on to address four groups: the leaders of America, white churchman, Black American citizens, and the mass media. The statement zeroed in on the issue of power: white people hoarded power while Black Americans had less. More specifically, “black power did not mean white disempowerment but the right of all people to exercise agency for themselves.”

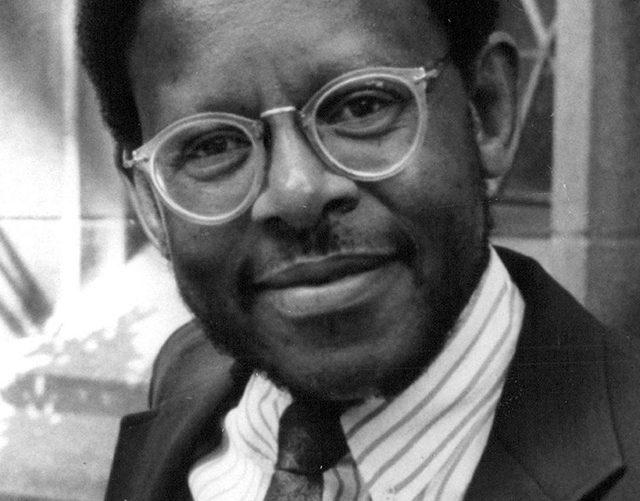

For many Black Americans, Black power exemplified their faith. A young James Cone understood his expertise in Christian theology as a way to fight oppression. Usually cited as the founder of Black Liberation Theology, Cone understood the suffering of Black Americans and the oppressed as the core of the gospel. The God of Moses and Jesus identified with the oppressed and empowered them to fight against injustice.

In the summer of 1967, race riots broke out in Newark, New Jersey and Detroit, Michigan. President Johnson created the National Advisory Commission on Civil Disorders, which was tasked with answering three questions: What happened? Why did it happen? And what can prevent it from happening again?

In their final report, the Commission found the white Americans responsible. “White institutions created it, white institutions maintain it, and white society condones it.” The report found inadequate housing, jobs, ability to vote, and police suppression as key causes to the riots. The Commission recommended more opportunities for community led feedback on policies, financial assistance, help for the poor, and a review to evaluate local police practices to reduce brutality.

The recommendations were not supported by federal or local officials.

Jesus proclaimed that all power and authority has been given to him, and then told his disciples to go and make disciples of all nations, baptizing in the name of the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit.

The current wrangling over power continues. Who should wield power and why? Who can be trusted with power?

Black Power Statement by National Committee of Negro Churchman, https://www.episcopalarchives.org/church-awakens/exhibits/show/transitions/item/183

Jemar Tisby, The Spirit of Justice: True Stories of Faith, Race, and Resistance, (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan Reflective, 2024).

6 Responses

Right on.

Can one hope for a denominational response?

Rebecca, I applaud your essay. My husband was going to Newark College of Engineering (now called New Jersey Institute of Technology) during the race riots of 1967. Charlie and I were further pushed to the left by this demonstration against racial bigotry that we saw in Newark, New Jersey, and the entire United States. Thank you for reminding us of the long history that Blacks have with discrimination in our entire culture. We should all be ashamed!!

The dilemma: God’s “empowerment to fight against injustice” is the empowerment to serve others, not to dominate them or force them to do anything. Do we really believe that this way of Jesus is the way of the Kingdom of God?

David,

I would argue that Jesus power is the power of love, which is power “with” or what Robert Capon (and Luther) called “left handed power.” The opposite, which I believe you reference as “dominate them” is power over or right handed power.

Where I think you fall a bit short is left handed power or power “with” often “forces” people to take account for their actions and deal with them. It doesn’t “force” them to change, that’s the realm of right handed power, and frankly it fails in that regard. As Capon says (and I paraphrase), God in love brings his son to the cross and allows the world to act in evil as it often does, and says, “There, try to take that away” or undo it or take any right handed power to change it. And we can’t. We simply look at it and must look at it. Hopefully, give account for it, which is probably the only power one can bring. I can’t make anyone do anything.

Here is what I know, when the church does not express it’s faith with as much power “with” that it can muster to live that love (active verb, not a noun) that reflects Christ on the cross, then we abdicate our faith and it is frankly pointless in the wider life of the city (wherever we live). Absolute power corrupts, certainly, but so does absolute powerlessness.

Thanks, Rebecca. This was a fabulous article for us to ponder for its history and its current relevance.

My wife and I are in the middle of watching the re-issued 12-part series “Eyes on the Prize”, re-issued recently but made in 1986, when many of the many people could still be interviewed. I highly recommend it to anyone who was sleep-walking through those years (as I was). It is important to realize the degree to which “Black Power” meant above all the right to organize as an independent party simply to gain access to basic rights such as (especially) the right to register to vote, which was entirely denied to African-Americans in such states as Mississippi. Meredith was shot on the second day of his solo march. Other Black leaders took it over and recruited black folks as they went. It was a turning point of refusing to be cowed by white racist violence, which was in ample display at the culmination of the march in Jackson.