I found it among the memorabilia my parents left in a file folder.

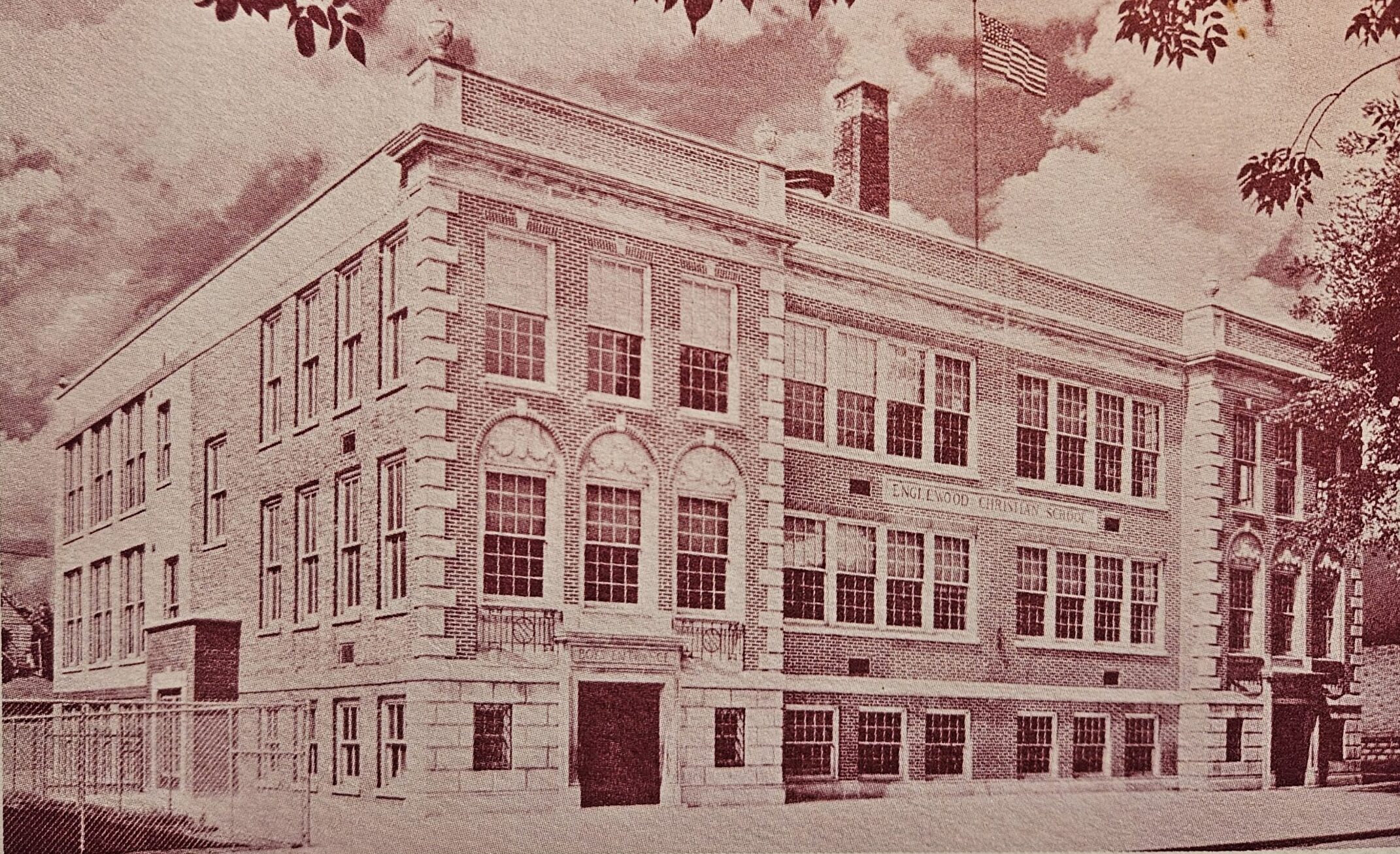

The Englewood Christian School Flash was the last newsletter prepared for the constituents of the school acknowledging that the school had been sold to the Chicago Public Schools, and that Englewood Christian would now affiliate with a Christian school in the southwest suburbs of Chicago. This was part of the pattern of White flight among Reformed Christians—and other faith groups—common to many urban centers in the midwestern United States.

The Flash was not my first exposure to the history of that time. In a course on Christian Reformed Church History at Calvin Theological Seminary, I, along with seminarian Ron Nydam, co-authored a paper on the White flight move of the churches and schools of Englewood and Roseland, another nearby community populated by Reformed Christians. Reading the school board and church council minutes of those years was a revelation for any number of reasons. Sadly, many of my boyhood memories of men I considered to be pillars of the faith crumbled before my eyes, based on decisions made and the stated, often racist, comments made in support of the decisions.

Years later, while researching again in preparation for my novel, Green Street in Black and White, I found the Flash. And it rocked my world.

As the farewell edition, it was printed as a keepsake, celebrating seventeen years of its publication and sixty years of the school’s existence. It had the typical features of newsletters of the era. Notes from the editor and the principal. Pictures of the graduating class with descriptions of their character in italics. Graduates’ last will and testaments. Picture of the basketball team—only boys, of course, and other student organizations.

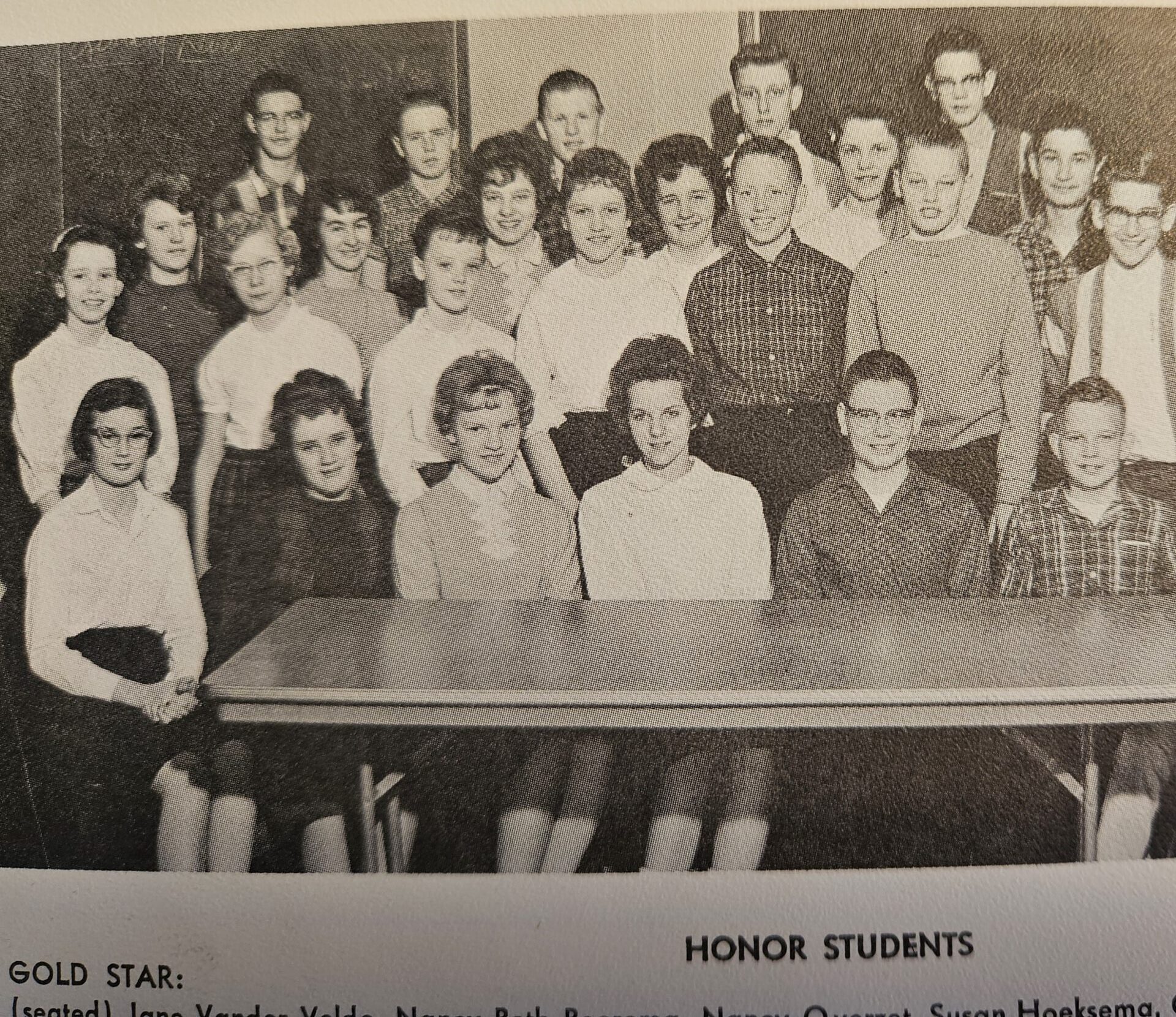

And the honor roll, with my sister there in the third row. I must have been sick that day.

But it was the “Roving Reporter” feature that first gave me pause. Two students who were interviewed had this to say when asked about the school closing and merging with a suburban school:

I would rather stay here if there were no Negroes. Our friends are going too. I don’t like going on the bus. I don’t like big classes. And

I’d like to stay in Englewood if there were no colored persons. I don’t like the idea of a big school. I wish all the teachers would stay.

As James Baldwin said, “Children have never been very good at listening to their elders, but they have never failed to imitate them.”

Not only were the student comments reflective of what they’d heard at home, they were printed in black and white for posterity, apparently endorsed by the newsletter editor.

If this were not enough to make me wonder, I read the following paragraph written by the Board President, explaining the reason for the school sale and closing:

Now our enrollment is decreasing rather rapidly, so that for fall we considered it unfeasible to continue as we have. When the Chicago Board of Education offered us $110,000 for our school, we accepted. Our school will be used to educate children of our neighborhood to whom God has given a different color of skin. We pray that in the future God may provide a way so that we may be able to witness to these people the wonderful grace of God as revealed in Christ. In the meantime, let us harbor no bitterness or resentment. If we do, we can no longer sing, ‘Red and yellow, black and white, they are precious in His sight,’ a song which has echoed often from the halls of our classrooms.

And there it was, on full, unabashed display. Enrollment was declining because of white flight. So, I wondered, was the move from Englewood led by institutions and then the community followed, or did the constituents lead the way and the churches and schools followed? Or was it a hybrid of sorts?

But there is also this, much more revealing. The assumption was that the Black families moving into Englewood needed the Gospel, couldn’t possibly be Christian, and the move of the school and its constituents is an opportunity for later evangelistic work.

Never was a thought given to the fact that Black students could fill those emptying seats and the school could stay to serve a new population. It would take some effort for Blacks and Whites to learn to live and learn together, but it was not even a consideration, even if they were encouraged to “harbor no bitterness or resentment.” Precious within God’s sight, but not enough for the readers of the Flash or leaders of the institutions making the decisions.

Finally, my eyes drifted to the photo at the top of the page containing the telltale quote. The all-male Board, dressed in suits and sports coats, white shirts and ties, smiling, the principal and officers seated in the front row. And there he was, my father, an officer of the Board.

One of the deepest regrets of my life is that we never had a conversation about those years or those decisions. When we moved from Englewood my sister and I were not part of the family discussion or decision. We, like so many kids at that time, were informed but not engaged. I’m certain that our parents’ motives, among other things, had to do with personal safety. I had been beaten on the street near our house, my father was robbed as he got off the CTA bus, and we had a brick thrown through our bungalow front window, knocking over our Christmas tree.

I don’t know if my parents were racists. I know my own tendencies toward a racist heart and when I’ve acted out of racist thoughts. My parents may have participated in some sense in racist decisions and actions during this period of White flight. I don’t know, for example, how my Dad voted on the decision to sell the school. I do know their conversations and actions later in life which persuade me that they at least struggled with the decision to move. But when I became a parent, I asked myself if I would have made different decisions and taken different actions than those my parents took in moving us to the suburbs.

And my answer is “Probably not.” Unless, of course, the church provided leadership and became a front porch for the changing community, bringing people together for conversations and commitments. Unless my family sensed we were not alone in our decision. Unless real estate practices were changed and laws passed against discriminatory lending practices and restrictive covenants no longer existed, victimizing and preventing Black ownership of property. Unless fear—of financial loss, of harm, of the threat of losing friendships and community—was somehow overcome and replaced by learning to love our neighbors in active, visible ways.

I’m grateful that today, even in Chicago and surrounding suburbs, you can find neighborhoods and schools that are a delightful mix of races and ethnicities, faiths, and communities, learning to live together and thrive. You can find churches that act like front porches for the community. And you will find exemplary Christian and public schools.

It’s been a slow, glacial change in attitudes and hearts, in legislation and real estate practices. Racism still exists in policies, legislation, and assumptions, and the hearts of many. But I’ve never been more hopeful, and grateful for Christians of all races and ethnicities who are leading the way

I wish my parents would have lived to see this day.

23 Responses

My experience was similar and different. I grew up in the “ghetto” of Bedford-Stuyvesant, Brooklyn, where my dad was the pastor of a Black RCA congregation. My ex-CRC parents were decidedly anti-racist, at least to the measure of that time. My brother and I were the only white kids in our neighborhood. Perhaps because of the esteem for my dad, we thought we were safe in our immediate area. But when my brother was assaulted, at the age of 11, and I got chased on my bike, and our church, next door, got broken into, and we with a younger sister and little brother, my parents made the decision to leave for New Jersey. It was a grief, for that was my father’s favorite pastorate, his first one, for which he was particularly well-suited, and he was never as happy in a church again.

Thank you, Daniel. “Grief” often accompanies decisions like this, even with the best of intentions.

Thank you Dave for having the courage to take an honest look at a painful page in our Reformed community’s history on Chicago’s South Side.

Dave, I read Green Street in Black and White and was informed of a situation I did not know about. I grew up as a Catholic and my husband as Orthodox Presbyterian and became Christian Reformed when we moved to Connecticut and looked for a church. We became CRC then. My family moved back to New Jersey and my husband left engineering for a teaching job at Eastern Christian. We had three children. The middle one was adopted and was half Black and half white. We enrolled him in Eastern Christian and did not think of ever being excluded. There were a number of backgrounds in that school so I did not see at first the racism in the CRC. I have been CRC now since 1968 and have seen much of it-even today. It is sad to say that a church that I once held so high has been leveled by the sin of racism.

Thanks for this honest reflection on your family’s participation in the white flight that occurred in so many cities.

Grosse Pointe Christian Day School welcomed Black students in the 1960s, so our third daughter had Black classmates and playmates throughout her years there. When she would describe a classmate, it would never be by the color of their skin, but in terms of what they were wearing. A number of us members of First CRC Detroit, located adjacent to the GPCDS, were active in promoting racial harmony and the integration of Grosse Pointe Park. I am not suggesting that no one in our congregation was racist, but that there were genuine efforts to break down color barriers and to live harmoniously.

Thanks for this positive account, Jack. It can be done.

Dave, I loved my years growing up in Englewood. Thanks for shining a light on those hard years. Maria Hiskes

Maria, so many good memories.

An honest tale that needs to be told again and again … all decent, “god-fearing” men … but the decision was made – white supremacy in many guises.

Dave, thank you so much for this honest look at the racial situation in Englewood and other places. It’s so easy for us to look back in judgment on the “leavers”, some of whom really did struggle with the decision to leave. As you so clearly point out, the situation was much more nuanced than we often realize. What would we have done indeed, if our children were being attacked? And the real estate industry supported and in some ways caused the unrest?

Dave, I appreciate this and I appreciated your book. We can learn from our history. We sent our kids to Christian ( largely segregated) schools. Today I question that “decision.” It was not so much for safety or economics but because of CRC tribal expectations, which were intense and exclusive. It was presumed that Christian education was a higher spiritual rung on the ladder. And we silently presumed “protecting” our kids was actually protecting our kids. Christian schools are wonderful, but they are inherently isolationist and privileged. I really believe Jesus would teach in a public school because his influence would be most needed there. I also believe that Christian schools can be light-bearers if and when they clearly commit to proactive integration ( race, behavior, cognitive ability, ethnicity) as part of their mission. It is all too easy for Christian schools to expect the public schools to absorb the “problem” kids.

RZ, for a picture of what Christian education can be, check out http://www.brightpromisefund.org.

So good Dave, thanks. The dilemma of a rock of anger/hatred toppling the tree of light/love in your dad’s sanctuary where his children sleep! It’s a parable of sorts (Roseland repeated almost identically) that has unfortunately been seen in other forms and similar dilemmas to this very day. I wrote an RJ Blog re First Roseland CRC (the RCA persisted long after the CRC left) but still wonder what choices I would have made then if were in my parent’s shoes.

My dad pastored in Cicero from 1963-1968. We faced our own racist tendencies with the Timothy Christian Schools refusal to accept black students. (The students from Lawndale were bused to DesPlaines.) My dad and some other pastors faced the school board and were told this was done out of love for neighbor. Cicero was a “whites only” area. The school board feared allowing blacks in would cause problems. I have a suspicion who they worried about the most. The CRCs of the south Chicago area bear the shame of a sordid history in regards to race.

Ken, two thoughts. First, this was not exclusively south Chicago in any sense. Sadly, in many urban areas of the U.S at that time, racism destroyed communities. Second, with regard to Timothy Christian, I recommend Christopher H. Meehan’s book “Growing Pains: How Racial Struggles Changed a Church and School,” Eerdmans.

I was born in Englewood but the family moved out shortly after. I’m sorry I didn’t get to know the place, but the people were not ready for that. It is a great shame.

Thank you Dave for reviving the memories. Our parents were quite close to each other and treasured their friendship. I remember my parents trying to walk the line between the racism we witnessed and the faith we professed. I also remember my father saying he preferred working for black families rather than some “Hollanders”. Jud Afman

Thanks for this, Jud. And check out “Meine Decker” in the novel. Even had a son named “Rich.”

Great article! But let’s not pretend…

Let’s bring it home, for the beasts of prejudice and bigotry still live within each of us. Let’s consider the marginalized in our own congregation or community. I call them the Avoided, Shunned and Averted (ASA for short). They are the dying, the caregivers for the dying, those in acute pain, those with long-term suffering, the fatherless, the homeless, the lonely, the handicapped, the poor, the addicted, the mentally ill,… darn! I’m forgetting a few (oh yes, recently incarcerated—is that one?).

Next, check your Thanksgiving guest list. How many of the ASA members from church are included? How many ASA members from church will once again feel the sting of being ignored??

Moses (God): “Be joyful at your festival—you, your sons and daughters, your male and female servants, and the Levites, the foreigners, the fatherless and the widows who live in your towns.”

Christ: “When you give a luncheon or dinner, do not invite your friends, your relatives, or your rich neighbors, but invite the poor, the crippled, the lame, the blind, and you will be blessed.”

Hi Dave

I think you were in my younger sister’s (Susan’s) class which was 5 years behind me. Mary and I left to begin what turned out to be a life long career in international missions in mid 1965 so we missed much of went on. I did know that our family in Roseland and several others refused to move and helped Roseland Chr. School as well as Pullman CRC at that time.

Some rather unusual things were happening which I woud like to discsuss when you get the chance.

Paul, love to have that conversation. How do I reach you?

Hi Dave,

I am looking forward to reading your book and wish my parents were still here to read it also! Your mother was a wonderful friend of my mothers from high school days at Calumet High School! Al and Marion were great friends until they were too old to travel back and forth to a Chicago! I have wonderful memories of their visits through the years! My folks moved to Holland, MI during the war but their friendship lasted a long time! Indeed difficult decisions were made then, as now, and May God grant us wisdom and sight to walk in the way of love!

So good to hear from you, Mary! And I clearly remember your mother’s advice to us during our dad’s last days.