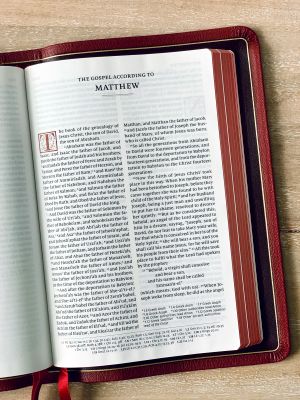

On a summer Saturday, I happened across a billboard on a stretch of highway I frequently travel as I run cattle up to Northern Michigan. The billboard encouraged folks to get to know Jesus by reading the Bible’s book of Matthew.

I spent a full semester during my doctoral program in a supervised study of the book of Matthew, and I can confirm from my experience that you will most certainly get to know Jesus there. The question is whether you’ll like what you find. I found the experience horrifying and life-altering. After completing a master’s degree in divinity and serving in pastoral ministry for six years, I found a Jesus in Matthew I’m not sure I recognized.

How could I have been a follower of Jesus that long, have had that much church experience and advanced study under my belt, and never really have looked at what Jesus actually said and did? Instead of what I was hoping to see, I saw a radical rebuke of what I had become: religiously right.[1] I had become someone who was right about everything and had the Bible to back me up in all my “rightness.” The Bible has a name for that: self-righteous.

Key to rebuking my religious rightness was Matthew’s demonstration of the radical inclusion of those who had been religiously wronged—and there were a lot of them. In Matthew, I saw a redefining of what it meant to be truly great (again) in the kingdom of Heaven. I noticed that greatness did not look like me or what I had become, regardless of my intentions. Greatness, to Jesus, often looked like “scum” to the church.

Matthew confronted the world with the person of Jesus and the impact he can have in the world through the transformation of an individual—when one’s soul begins to matter more than gaining the world (Matthew 16:26).

Here are the opening words from the book my professor assigned during my doctoral study of Matthew. They point out the challenge we face as well as the repercussions of not accepting the challenge. These words are now, believe it or not, 50 years old, but feel as though they could have been written yesterday:

Even if we cannot believe that God is dead, it is clear that something has died. And that [something] is the capacity of most of us for conducting our daily lives as if He [God] were about, as if His existence and His interest in our affairs were fairly probable. This incapacity may have already had drastic consequences. It may be an honest explanation of the barbarism and confusion that attack our politics, and it may help to account for the turbulence in the private climate of our age [emphasis added].[2]

I should add that I am well aware that religion itself is the root of much destruction. What I saw Matthew’s Jesus doing was not proposing to advance a religion, but a reality that transcends all religions.

The Professor’s Office

After hours of research, reading, translating Greek, and writing reports, I completed what the billboard and my doctoral program demanded of me: I had deeply studied Matthew’s gospel. I had seen the Jesus Matthew insisted I see, and it was time for my final review with my advisor.

As I entered my professor’s office, I found him where I always did: leaning back in his chair, hands folded across his belly, Diet Coke within reach, and a smirk on his face that seemed to perpetually hang there. It was a smirk that I have come to appreciate but have yet to emulate. I simply can’t reproduce it—probably because I can’t reproduce what was behind it.

I suspect what lay behind the smirk was an assurance that you control nothing in life but simply participate in the fun going on right in front of you. This might be especially true when the “fun” was a floundering doctoral student who thought he had it all figured out only to have just deeply read the book of Matthew . . . and realize there was big trouble brewing. Why not smirk?

I always seemed to bring the guy some sort of fun—he had taught several of my master’s level classes as well. It seemed he had quite a bit of fun with most of us, actually. Maybe because we were always floundering. The only students he seemed frustrated with were those who were convinced of things they knew little about. (That part was fun for the rest of us.)

There he was again, smirking as I walked into his office. “Well,” he said. “What did you think [of Matthew]?”

“I think I’m going to Hell,” I said. “Unless Jesus decides otherwise.”

He smirked again, only wider with a “mission accomplished” sort of look and leaned back farther in his chair.

Now if an ordained minister doctoral student confesses his belief that he is going to Hell, shouldn’t that remove the smirk? Shouldn’t the smirk be replaced with a more concerned expression? Perhaps my professor should have at least leaned forward a bit to demonstrate some concern or slap me out of it. He did no such thing. He just kept smirking and leaning back. It was almost as if he’d achieved what he intended. It’s as if he had me right where he wanted me.

In fact, he seemed cautiously optimistic. In what? I’m not sure. I wish I had asked him. But I was in too much shock. Perhaps it was his belief God was up to something that didn’t require panic. He may have known that nothing actually requires panic. Maybe that was his secret.

“We don’t know anything, do we?” I asked with some dejection in my voice, realizing my world was one that required accurate information upon which to function.

“Not much,” he said with that smirk. “Not much.”

The more I read, the more I acquire, the more certain I am that I know nothing. –Voltaire

Most would find that admission frightening coming from a seminary professor. How could there not be answers and, of all people, how could he not have them? That’s why we come to church and seminary, right? To get answers? Isn’t that why we go to Matthew’s gospel and the Bible? For answers?

I recall a bumper sticker I read in the late ‘90s that mocked this idea. The words on the bumper sticker transposed the frequent Christian cliché “Jesus is the Answer” with a new proposal: “Jesus is the Question.” This is the Jesus I found in Matthew.

Instead of answers I found questions—not the least of which the disciples themselves asked: Who then can be saved (Matthew 19:25)? I wondered how living an eternal life as Jesus described was even possible. I wondered how I could avoid exchanging my soul for the world, given the standards Jesus laid out in Matthew.

I realize that asking these questions can put a person into a narrow band of navel gazers (as my father would call us). A narrow group of people who may simply overthink things. I acknowledge that possibility, yet have been unable to block out the question.

I had come to seminary for answers and found only more questions. Yet my professor’s reaction and lack of answers also set me at ease somehow. That and his smirk, I suppose. The ability to not have all the answers and yet still have some kind of peace seemed reassuring. I’m not entirely sure why. Perhaps I will get there one day myself.

“It’s a little embarrassing that after 45 years of research & study, the best advice I can give people is to be a little kinder to each other.” — Aldous Huxley

My professor allowed for mystery, which was a concept that frightened me early in my Christian life. The church in general still finds it terrifying. We have creeds and dogmas and such to clarify something profoundly mysterious. That way we can be sure we’re getting it right and, perhaps more troubling, prove others are getting it wrong. I would discover that the idea of “getting it right and having proof others were wrong” was a key principle of the church of my day as well as that of Jesus’s day. Life would teach me that dogma and doctrines only existed to aid in my desire to feel important and think well of myself.

The doctrine you desire, absolute, perfect dogma that alone provides wisdom, does not exist. Nor should you long for a perfect doctrine, my friend. Rather, you should long for the perfection of yourself. The deity is within you, not in ideas and books. Truth is lived, not taught. – Herman Hesse, The Glass Bead Game

My professor never tried to save me or assure me that I would get to Heaven. He didn’t seem worried about what was going to happen to me when I was dead. He only seemed concerned with my pursuit of Jesus while I was alive. And, oddly, even that didn’t seem to bring him much worry—although it was keeping me up at night!

The professor of whom I speak is Dr. Jim Brownson. He was, at the time, a New Testament professor at Western Theological Seminary. He and his smirk have left an indelible engraving on my heart—an engraving in the shape of abject humility when considering the magnitude, magnificence, and mystery of all that surrounds the idea of God particularly as embodied in the person of Jesus Christ.

It is indeed my hope that, in some small way, I can carry on what he instilled in me—a rabid desire to pursue Christ even in the midst of the impossibility of that very task. I hope I can offer to others the message he showed me in Matthew: the radical inclusivity of Christ for all those the world considers to be the least and deems unclean. People like me. Perhaps when those realities really sink into my soul the way they registered in his, I too will be able to simply smirk at the insanity of life knowing God. After all, the whole world is in his hands.

[1] An intentional parody of the “religious right” in America.

[2] Bruner FD. Matthew 1–12: The Christbook, Revised and Expanded. Grand Rapids, MI: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 2004: 3.

*****

Before you go, could you take a few moments to give a year-end financial gift to the Reformed Journal?

It is simple, quick, and safe.

Your gift will keep our thrifty enterprise healthy and moving forward in 2026.

Click on the purple button below for info on the various ways to give.

Thank you very much!

Reformed Journal is funded by our readers; we welcome your support. This holiday season, we call your attention to our “But Wait…There’s More!” deal—three new books sent to you in 2026!

For a gift of $300 or more between now and the end of 2025, or a monthly gift of $25 or more in 2026 and you’ll receive these books. (Canadians: due to shipping costs and exchange rates, we are asking for a gift of $450 (CAD) or $38 monthly.)

Click the purple button above for more details on this year’s special “But Wait, There’s More” offer—three new books by Reformed Journal contributors in 2026! You can use the same page to give an online gift of any amount or to find info on giving by check via mail.

Checks may be mailed to:

PO Box 1282

Holland, MI 49422